As if we don’t have bigger tofu slices to fry–with 57 days till the election, we absolutely do–the academic/activist left is atwitter (pun intended) about yet another blackface scandal. This time, it’s Jessica Krug, African and Latin American history professor at George Washington University, whose identity as “Jess La Bombalera” was, as it turns out, fictitious: she grew up Jewish in Kansas City. Facing imminent unmasking by colleagues who suspected that something was awry, Krug published a self-excoriating screed on Medium, in which she admitted to fabricating “a Blackness that I had no right to claim: first North African Blackness, then US rooted Blackness, then Caribbean rooted Bronx Blackness.”

This mess comes to us just a few years after the exposure of Rachel Dolezal, the NAACP official who cultivated an African-American-passing appearance and sparked a debate on whether “transracial” was a “thing,” and a few months after the death of author H.G. Carrillo (“Hache”) of COVID-19, which exposed his lifelong fabrication of a Cuban-American identity. Because of the nature of the identity-manufacturing–white people posing as black–Krug and Dolezal drew understandable ire, and both scandals erupted amidst waves of uprising about racial inequality.

Plenty of personal trauma and pathology is evident in both stories, but Durkheim taught us to see even the most personal phenomena as social facts. Given the progressive obsession with performance, these scandals are a Petri dish for dissection and, faithful to the trappings of the genre, most of these have revolved around the authenticity (or lack thereof) of apologies. But I found an especially insightful twitter thread by Yarimar Bonilla, who astutely remarks that it was “[k]ind of amazing how white supremacy means [Krug] even thought she was better at being a person of color than we were.” Bonilla offers revealing examples of how expertly Krug trafficked in the tropes of progressive oneupmanship:

She always dressed/acted inappropriately—she’d show up to a 10am scholars’ seminar dressed for a salsa club etc—but was so over the top strident and “woker-than-thou” that I felt like I was trafficking in respectability politics when I cringed at her MINSTREL SHOW. In that sense, she did gaslight us. Not only into thinking she was a WOC but also into thinking we were somehow both politically and intellectually inferior.While claiming to be a child of addicts from the hood, she boasted about speaking numerous languages, reading ancient texts, and mastering disciplinary methods—while questioning the work of real WOC doing transformative interdisciplinary work that she PANNED. She consistently trashed WOC and questioned their scholarship. She even described my colleague Marisa Fuentes as a “slave catcher” in the introduction to her book. Kind of amazing how white supremacy means she even thought she was better at being a person of color than we were.That pathology remains evident in her mea culpa article. Somehow she manages to remain ultra woke and strident, still on her political moral high horse, caling for white scholars to be cancelled –in this instance her own white self.

Yarimar Bonilla on Twitter, Sep. 3, 2020

Bonilla is not the only scholar who blamed white supremacy–in this particular case, Krug’s whiteness–for the scandal: elsewhere on twitter, Sofia Quintero quipped that “[n]othing says white privilege like trying to orchestrate your own cancellation.” But I think there’s something else going on here. As many people have observed, Krug materially benefitted from her deceit, through fellowships and opportunities open to underrepresented people of color. The benefits, however, don’t end there, and it’s time to be honest about this. Overall (no matter how much our Attorney General chooses to ignore this), white people enjoy preferential treatment across the board, starting with the very basic good fortune to avoid humiliating, dangerous, and sometimes lethal encounters with the police, and continuing through intergenerational wealth, opportunity, and representation. However, there are pockets and milieus–and they are not minuscule or insignificant–where being a person of color confers real, valuable social advantages. I happen to know this milieu, the academic-activist pocket, quite well, and I think the social dynamics in it explain a lot. It’s not just scholarships and fellowships (though there are examples of material benefits.) It’s the mantle of authenticity, the uncontested ability to hold a moral high ground, and the sometimes-explicit, sometimes-tacit permission to treat others publicly with disdain.

The moral high ground is not unrelated to material benefits in academia (such as they are, given the initial barriers to academia for people from marginalized backgrounds in the first place), but the mantle of superior morality in itself is a precious commodity for some academics/activists. Because white people cannot be black (or can they? Read Adolph Reed’s take on racial essentialism, if you can get around his disregard for Caitlyn Jenner), the next best thing is to be the best white person they can possibly be, which is why we engage in the pageantry of racial confessionals every time yet another horrific killing of a black person produces a swell of uprising against racial inequality (that there’s immense grief and rage is understandable, and it has to go somewhere, but it’s telling that it goes into this variant of moral theatre.) Krug and Dolezal knew full well that, in this competition, it’s turtles all the way down, and simply drew the obvious conclusion: the only way to win the performative goodness race, the ultimate white progressive oneupmanship, is to subvert the whole thing by becoming black yourself.

Except, as Bonilla astutely tells us, and as Krug and Dolezal have taught us, it doesn’t end there, because it turns out that white people haven’t cornered the market on performative goodness. It plays out in remarkably similar ways among academics and activists of color, where strident and edgy performance of authenticity confers the symbolic benefits of being better than other (less radical, less woke, more white-conforming) nonwhite people. Inevitably (and this is true even if you aren’t a white person pretending to be nonwhite), someone’s going to be woker than you, purer than you, more authentic and edgy than you (as Touré Reed wrote, the demand for this kind of performance is a problem in itself.) One’s own goodness is a helluva drug; one needs larger and larger doses, ad infinitum. On the brink of being unmasked, Krug correctly deduced that the only move left on the chessboard was self-cancelation: embracing an ethos of zero forgiveness and zero redemption must exact the ultimate price. After all, she says, “my politics are as they have ever been, and those politics condemn me in the loudest and most unyielding terms.”

Is there another way out of this grim festival of condemnation and self-condemnation? Yes, but only if we see the recent slew of blackface scandals differently. Whether or not Dolezal or Krug “get”, to use another odious idiom from this milieu, to be redeemed, is not particularly interesting to me; like Bonilla, I don’t think we can or should spend energy marinating in the bacchanalia of punishment that this sort of thing dredges up. Instead, I suggest that people like Dolezal, Krug, and Carrillo–like the many people who “passed” before them across racial lines in America–have valuable lessons to teach us about the social cost-benefit calculus of passing. If we view these scandals as social facts, we learn where the perceived advantages and drawbacks lie, and might come to important conclusions.

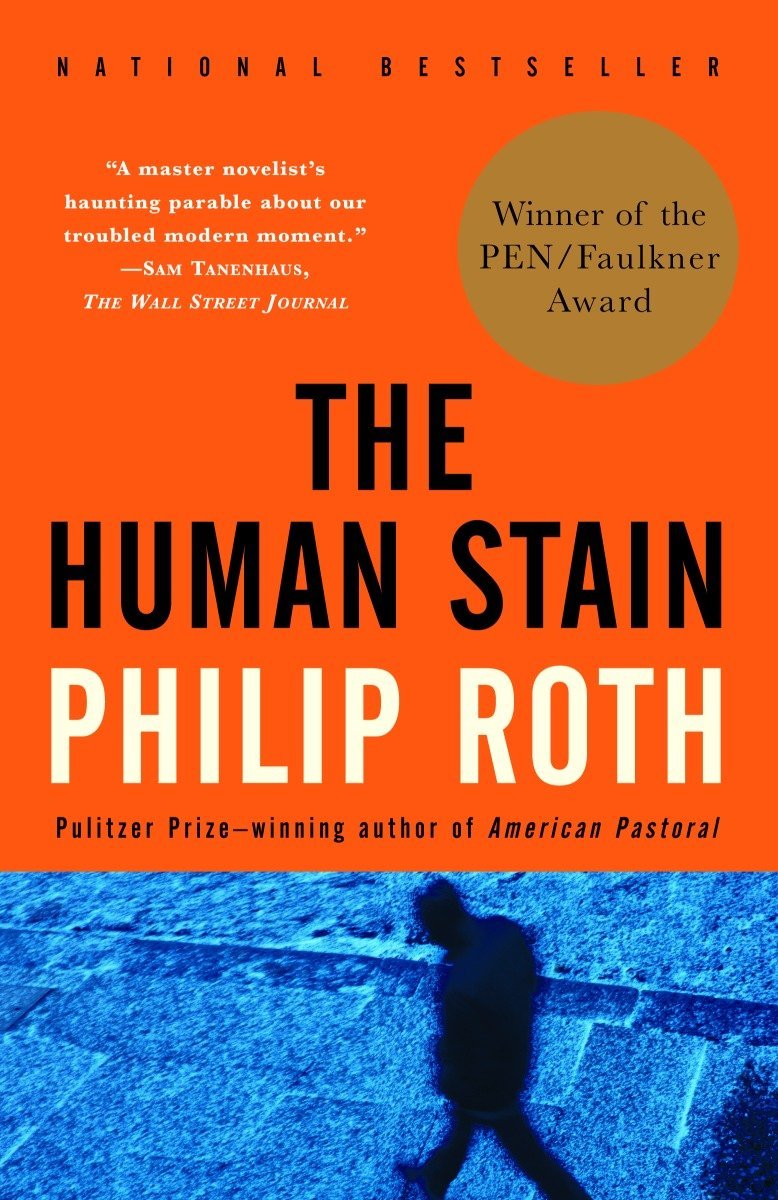

I remember reading Philip Roth’s The Human Stain with great interest and great discomfort. Roth’s protagonist, Coleman Silk, is an academic widely perceived as a Jew, whose life is destroyed following innocent quip at a classroom–using the word “spooks” for “spies”, a term that also carries racially-derogatory connotations. Subsequently, it is revealed that Silk is actually African American but had been passing as a Jew since a stint in the Navy. He completed graduate school, married a white woman and had four children with her, never revealing his African-American ancestry to his family. As Roth writes, Silk chose “to take the future into his own hands rather than to leave it to an unenlightened society to determine his fate”.

The Human Stain is crafted around a real story–the witchhunt against Roth’s friend Melvin Tumin for a similar innocent utterance. It’s not the only example: John McWhorter relays a similar incident, and if you want something more recent, this idiotic USC reaction to absolutely nothing is a prime example. Roth’s spin on this story of “cancelation” teaches us the same conclusions: endless competitions of moral superiority, lacking in compassion and forgiveness and hingeing on identity as the ultimate arbiter of all things, end up with the snake swallowing its own tail. It’s not a coincidence that Roth chooses to contrast the witchhunt with its logical conclusion: it’s the perfect confluence of our search for racial benefits and our appetite for meting out costs.

In other words, Krug, Dolezal, et al. are being reviled for being exceptions, aberrations, when they are mere corollaries of the game that everyone around them plays on the regular–a game of excoriations, public apologies, public rejections of apologies, obsessions with performance and appearance. I’m going to venture a not-very-wild guess that they are not the only ones. People of all colors in this mileu are so invested in this game, so I’d be surprised if there weren’t other passers around, trying to circumvent the white goodness competition only to find themselves playing the person-of-color goodness competition. Racism and racial inequality have wrought many ills, but this is one we can actually fix ourselves. Let’s stop playing this game, okay? It’s occupying so much cultural room that there isn’t enough left to do the actual work of racial equality–donating to worthy causes, supporting political candidates that move us farther in terms of racial and economic equality, revamping business to allow all families the chance of intergenerational wealth. How about, rather than tying ourselves up in knots about how we can come up with more, better, symbolic representation of our goodness, we call it quits and focus on quietly and efficiently doing the right thing? We could if we learned the right lesson from these scandalous morality tales, but I’m not holding my breath.

For a more lighthearted take on this, I highly recommend this hilarious conversation between Trevor Noah and Michelle Wolf. It suffers from some of the essentialist ailments I talked about (if she “passes” for a person of color, how can she “cry her way out of a ticket?”), but it’s so enjoyable nonetheless.