As has been my custom, I’m going to provide blog endorsements for criminal justice propositions and candidates as the November election approaches. Today we start with the top of the ticket–candidates for President and Vice-President.

If you’re anything like me, you’ve been getting dozens of idiotic political fundraising gambits via email and text. One of my favorites was the faux survey: “Do you prefer Sanders and Klobuchar/Biden and Warren/Harris and Castro to Trump and Pence?” To which I often replied, “I prefer a colonoscopy and a root canal to Trump and Pence.” I think what we have here is not what I would have wanted, but it’s nowhere near a colonoscopy and a root canal, and it’s a light-years-far cry from Trump-Pence.

***

Suppose, for your birthday, you receive a catalog with two gift choices: a steaming pile of poop and a basketball. You must have one or the other; if you pick, you get the one you chose, and if you don’t pick, one will be chosen for you. You can’t opt out. Alas, you wanted a pony. But a pony is not on offer.

What do you do? You might pout, you might shout, but eventually you pick the basketball. Because there’s something you know for sure: you don’t want the pile of poop.

You don’t scribble, “I WANTED A PONY!!!!!” with your colored pencils all over the catalog. There is no #%^@ing pony. There’s only poop and basketball.

***

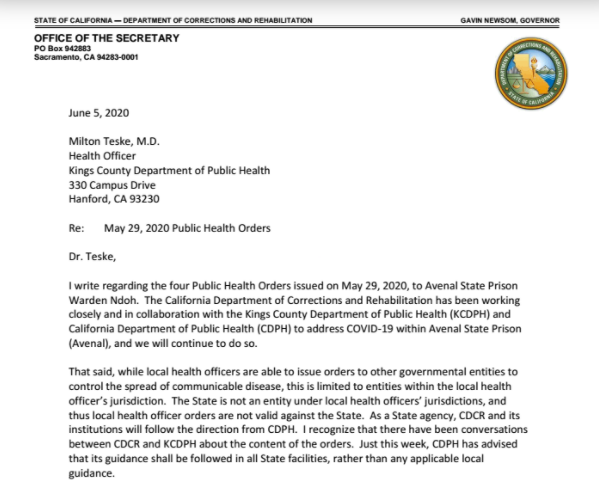

Six years ago, an Orange County federal judge, Judge Cormac Carney, ruled that the death penalty in California was cruel and unusual because of the delays in its administration. This decision provoked much excitement in the anti-death-penalty community. It did not mean immediate abolition, because it was just one habeas case. But it could lead to abolition, and all the Attorney General had to do was refrain from appealing the decision and get out of the way. At the time, I organized a petition, which 2,178 people signed, essentially urging then-Governor Brown and then-Attorney General Harris, both of whom were personally opposed to the death penalty, “don’t just do something! Sit there.” Many lawyers and advocates were extremely excited about the prospect of finally getting to work on ridding ourselves from the shame and the expense of California’s broken death penalty. And then, two days before the appellate clock was to run out, the AG’s office decided to appeal the decision.

To my surprise, and to their credit, one of AG Harris’ assistants called me on my cellphone and explained why they decided to do so. They interpreted Judge Carney’s decision as making new law on habeas, which is prohibited, per Teague v. Lane (1989), because of retroactivity issues. The technical wrinkle is this: habeas petitioners’ cases are already final, and if a new law is announced in their cases, it cannot apply to similarly situated defendants, because their cases are also final. So the Supreme Court decided to relegate habeas to the law of yesterday, which is unfair and outrageous, but it is technically the law.

Jones v. Chappell then landed at the Ninth Circuit as Davis v. Jones. At the oral argument, Jones’ attorney made a valiant effort to argue that Judge Carney did not make new law, but rather applied good old Furman v. Georgia. The effort failed, though it did have some merit. The decision was a big disappointment, and we ended up with six more years of a death penalty in which no one was executed but your tax dollars, and mine, funded $150 million a year per death row person in litigation fees. Our effort to repeal via voter initiative didn’t work, and met with nasty resistance in the form of a competing, misleading, unjust proposition, which is still tangled up in litigation to this day. It also met with the preciousness of progressives who believe that the good was the enemy of the perfect, and astoundingly voted no on abolition. So it went until Gov. Newsom finally pulled the plug, but of course, without judicial support (or legislation,) we’re still paying the litigation fees, and we will continue to pay until some brave judge does something or until a majority of Californians finally votes to abolish.

I was very upset about the AG’s decision. I thought it was the wrong call, policywise and moralitywise, and said so on numerous occasions.

I am writing this because phone calls from news agencies looking to do some muck racking have already begun. I’m going to decline any and all interviews about Harris, and I want to be crystal clear why. My target audience is the folks who were hoping for a different ticket. I explained the background above to clarify that I, too, had a different ticket in mind. I wanted Elizabeth Warren to be the Presidential nominee. But Elizabeth Warren is not on the ticket.

Joe Biden and Kamala Harris are.

I want to make it crystal clear that I am shelving any and all reservations about the Democratic 2020 ticket, and am urging you to vote Biden-Harris, with or without enthusiasm. Your enthusiasm is not that important (though, if you can muster some, you’ll feel better.) Your vote is. Monumentally so.

In the coming months, we will hear a lot about who Biden and Harris are, but one thing I’m pretty clear on is that they are colossally different than the criminal junta that has been running things in the last three and a half years, buying their way to power through treason and backroom deals with enemies, locking up children, letting families starve, making nepotistic appointments of unsuitable, barely-literate idiots who ruin whatever they are in charge of, destroying our precious planet, sending government goons to beat and abuse protesters, encouraging and goading non-government goons to shoot, run down, and murder people, trafficking in horrific tropes to ally themselves with actual Nazis.

The situation, in short, is this, my friends. Behind Curtain no. 1: Nazis. Behind Curtain no. 2: not Nazis.

The pony is not on the ballot. The bedrock of our democracy is. You’re not getting a custom-fit ticket, you’re choosing from a catalog with two products. The choice is obvious.