The union that represents health care workers, clerical staff, custodians and other prison employees, SEIU Local 1000, has filed a wide-ranging grievance against CDCR and CCHCS (the Federal Receiver’s prison health services) for employing them, throughout the state, in unsafe conditions. Megan Cassidy for the San Francisco Chronicle reports:

The grievance, filed July 28, alleges that union officials documented safety violations at all 35 prisons owned and operated by the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, or CDCR.

“Some of these prisons have already had serious COVID-19 outbreaks,” the grievance states. “(Prison and prison health care officials) should still be able to prevent outbreaks if they take all possible and reasonable steps to prevent them.”

The grievance lists numerous violations:

- Inadequate supply of hand sanitizer machines and disinfecting wipes

- Common areas at worksite are not being cleaned throughout the day

- No training received on the state’s COVID-19 health and safety guidelines

- Employees are not getting notice when someone at your worksite has tested positive for COVID-19

- Not everyone at institution wears a mask

- Six foot physical distance is not being maintained at worksite

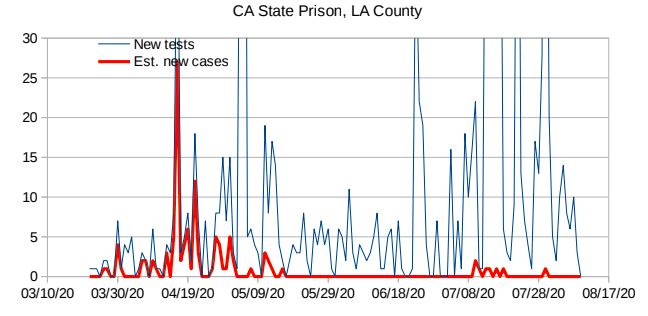

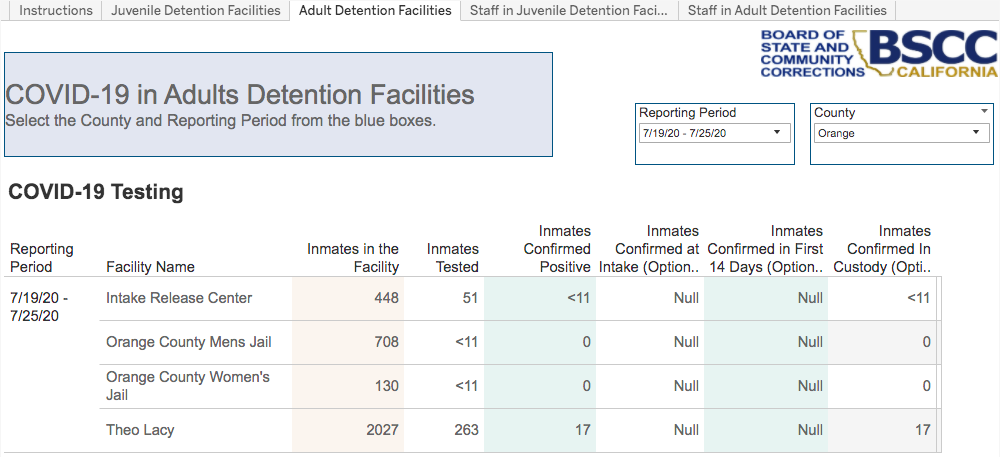

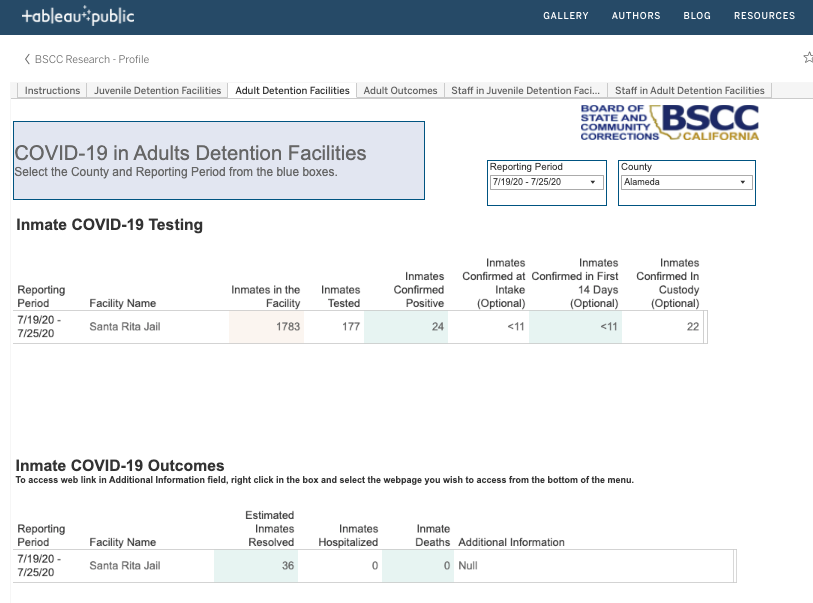

- Failure of adequate testing of staff and inmates

- Transfer of inmates without adequate testing [this pertains to the infamous transfer from Chino, which brought COVID-19 to Quentin and Corcoran–HA]

- Failure to quarantine or isolate inmates with suspected exposure

- Failure to maintain adequate internal command or control

- Failure to provide safety protocols to protect staff from infection

- Inadequate supplies and types of PPE

The union demands taking the following steps:

- Take all necessary steps to ensure employee health and safety

- Ensure that each institution has a COVID-19 incident command center with both medical and custody staff

- Have a clear written plan for spaces/areas that will be utilized to isolate/quarantine suspected and COVID-19 confirmed inmates at each institution.

- Ensure that management at all levels understands their responsibilities and role in preventing the further spread of COVID-19.

- Halt the movement of inmates between prisons and intakes from counties [this is crucial because, as I learned today on Twitter from people on the inside, transfers are scheduled to resume this coming Monday – HA]

- Ensure that DAI and CCHCS are doing everything possible to maintain six foot physical distance between persons (including allowing all employees possible to telework), providing adequate hand sanitizer and disinfectant wipes and are enforcing that everyone wear masks/or face coverings

- Ensure that all employees are trained with the latest State of California health and safety guidelines and that all employees are noticed about possible COVID-19 exposure at their worksite.

This was a long time coming; I’m surprised the union is taking these steps only now, but there’s something else that bothers me. In Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Hound of the Baskervilles, Scotland Yard Inspector Gregory asks Sherlock Holmes, “Is there any other point to which you would wish to draw my attention?” Holmes replies, “To the curious incident of the dog in the night-time.” Gregory says, “The dog did nothing in the night-time.” To which Holmes answers, “That was the curious incident.” I bring this up because, if there’s any union that should expected to vociferously defend the interests, safety, and health of its members, it’s the strongest union in California— the CCPOA.

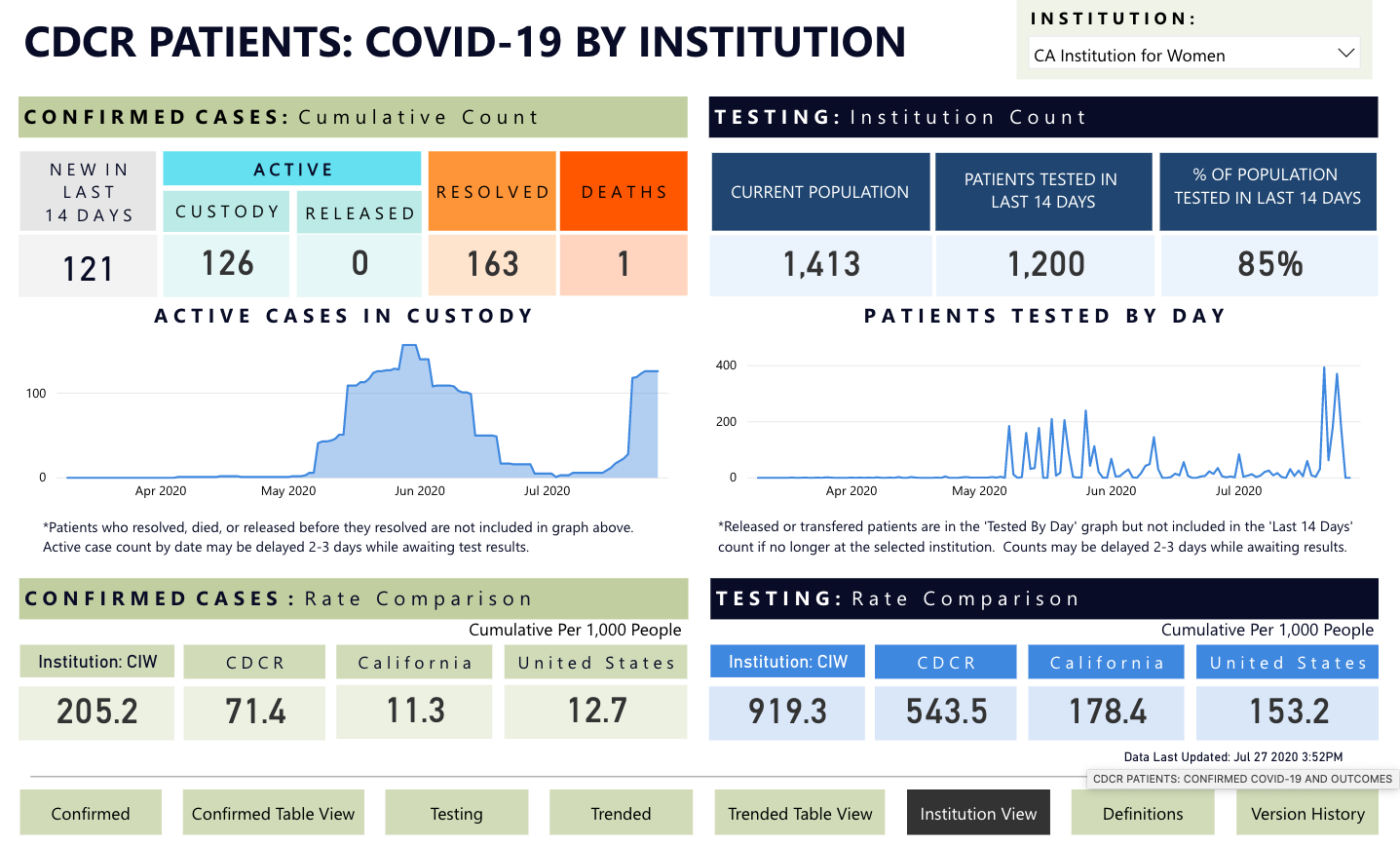

I’ve spent quite a while today on the CCPOA’s website, trying to find a sliver of a reference to COVID-19. Nothing on the front page; nothing under “news and information.” They do take care to mention a study according to which PTSD rates among prison guards rivals that of war veterans and to take pride in a 5% salary raise from 2019, but nothing whatsoever about the obvious. CCPOA guards face as much risk from the virus as the workers represented by SEIU Local 1000; the CDCR reporting system does not distinguish between guards and other staff members. To-date, CDCR reports 1976 COVID-19 cases among staff, as well as eight deaths.

CCPOA is not a particularly timid union. As Josh Page explains in his wonderful book about the union, CCPOA has been at the helm of much of the punitive animus in California, branding itself as a tough-on-crime organization and partnering with (or puppeteering) Crime Victims United of California, with whom CCPOA shares numerous board members. CCPOA and CVU are largely responsible for the public perception of punitivism as natural and ubiquitous, a perception not shared by many survivors of violent crime. And here we have a matter that’s not about fancy penological philosophy, but is actually the bread-and-butter of what a union is supposed to do: protect its members’ health and safety on the job. Instead, here’s what the Sac Bee reports about their salary negotiations with Gov. Newsom:

California correctional officers would take one furlough day per month and defer raises for two years under a proposed agreement their union has negotiated with Gov. Gavin Newsom’s administration.

The California Correctional Peace Officers Association’s two-year agreement appears to be the first deal a state union has reached with the administration over pay cuts Newsom proposed for all state workers to help address a projected $54 billion budget deficit.

The tentative agreement will require a vote from the union’s 26,000 members to pass and will need approval from the Legislature.

The agreement uses a personal leave program to reduce officers’ pay by 4.5% — roughly the equivalent of one day of work per month — for two years. In exchange, the officers receive 12 hours of paid leave per month, the equivalent of one and a half days of work.

A 3% raise the officers were scheduled to receive July 1 is deferred until July 1, 2022.

The agreement would reduce the state’s spending on correctional officers by 8.99%, or about $395 million, according to a cost summary of the agreement. Correctional officers make up a large share of the state’s general fund spending on its workforce, accounting for about a third of general fund payroll spending.

Newsom’s original proposal of two unpaid leave days would have reduced the state’s spending on the group by 9.53%, or about $419 million, according to the summary.

The agreement softens the impact of the cuts on correctional officers’ pocketbooks by suspending a paycheck deduction that funds the health care plans they’ll use in retirement. That change allows workers’ to keep 4% of their paycheck that had been going to future health care costs.

The state also would cover an increase to health insurance costs of .54 percent, according to the summary.

The deal would suspend holiday pay for seven of the 11 state holidays, eliminate one personal development day for the term of the agreement, suspend night and weekend differentials and make other tweaks to pay.

This is not great for CCPOA, though it does somewhat soften the blow of the salary cuts. But how could CCPOA negotiate with the Governor, amidst a pandemic, and not mention their working conditions, even in passing?

The curious thing about the guards’ COVID-19 interests is that the best thing that can be done for them, which is, obviously, mass releases to allow for social distancing and minimally competent healthcare, stands in opposition to what their leadership has advocated for in the last forty years. CCPOA built its power advocating for more and longer prison sentences, getting its political cache from being “the toughest beat” and from the sheer enormity of the California correctional apparatus. But this does not necessarily reflect the rational self-interest of its members, which even in ordinary times would find it safer and easier to wrangle and supervise fewer people in a less crowded facility. In that respect, the virus is not so much reversing the interests of the guards as it is putting them in clearer focus. And if this is the case, then it seems that CCPOA is not really representing its members properly, and we’re seeing a pretty dire example of political capture.