Yesterday, on July 9, we held a press conference at San Quentin to draw attention to the conditions inside the prison. We invited Gov. Newsom to participate, but he did not attend. His absence was glaring, as one of the demands of the protesters is that he at least make the effort to visit the prison and see the conditions with his own eyes.

You can read about the press conference in the Guardian, the Chron, and the ABC News website. It was incredibly moving to hear from mothers and spouses of people on the inside about the desperation of their loved ones. James King, state campaigner for the Ella Baker Center who is formerly incarcerated in San Quentin, shared a letter from a friend of his currently behind bars that truly conveyed the horror of dealing with this pandemic. Shawanda Scott spoke of the loving home she has waiting for her son. These testimonies undercut the myth that no one is waiting for those afflicted on the outside, and that, as James said, “the minute they are released… tens of thousands of families will be here at the gate to welcome them with open arms.” Adnan Khan of Re:store Justice spoke very movingly of the tendency to dehumanize people in prison. Dr. Peter Chin-Hong from UCSF spoke of the history of contagion in prisons (“prisons are incompatible with health.”) It was terrific to have legislators with us: Marc Levine, who has been on top of this from the very beginning, Scott Weiner, Ash Kalra, and Rob Bonta were with us. Public Defenders Brendon Woods and Mano Raju, and San Francisco District Attorney Chesa Boudin, also came to lend support. And, it was amazing to hear from Eddie Zheng, and from more family members of people incarcerated at San Quentin, at the open mike section.

What really inspired me was that the families spoke without spite or rancor. They said they were not interested in blame, only in saving their loved ones from illness and death. My mentor Malcolm Feeley, who started the ball rolling on this by emailing me a couple of weeks ago saying “I’m so pissed”, said that this is the new victims’ rights movement: the victims of the state’s indifference.

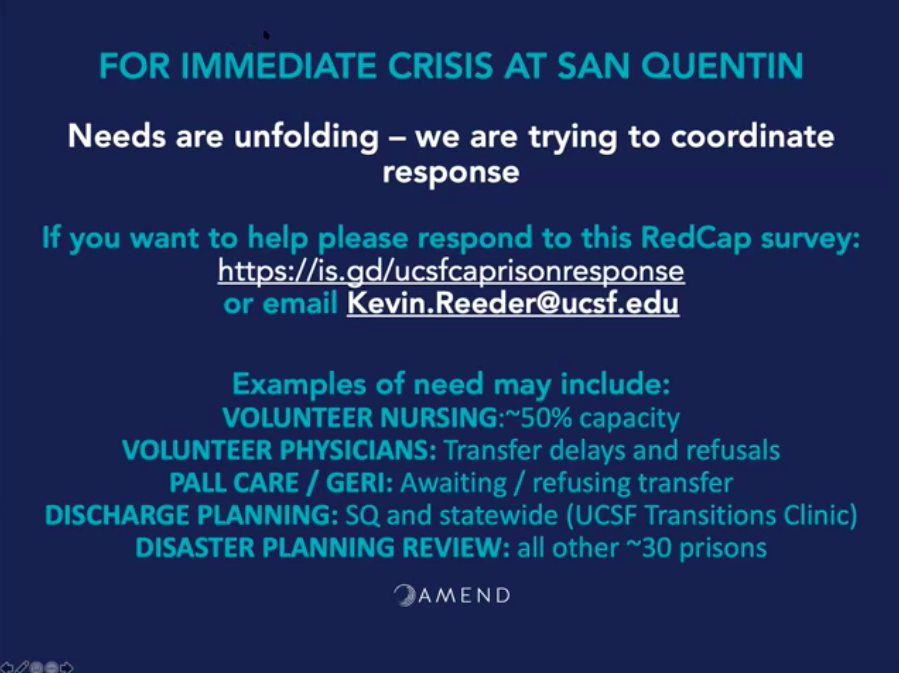

Co-organizing the press conference was inspiring. There is no way a single organization or demographic could’ve put this thing together on their own. It took a diverse coalition of talent and experience, united by our passion to save people and put an end to what is probably the worst medical scandal in prison history. I am so grateful to my co-organizers–most of whom put an enormous amount of effort into this and stayed behind the scenes. They are an amazing group of people and I hope we can keep up the pressure on Gov. Newsom to do the right thing.

A few people asked me to post my speech, so here it is:

***

Hello. My name is Hadar Aviram and I am a law professor at UC Hastings. I am the author of an open letter to Governor Newsom asking him to release people from prison to save lives. I speak here on behalf of more than 400 of my colleagues [now closer to 500–H.A.], who signed the letter: criminal justice experts, prison law experts, public health experts. We are asking Gov. Newsom to do what he knows, in his heart of hearts, is the right thing.

An old Cherokee story tells of a wise grandfather and his grandson. The grandfather says, “Son, within each of us there is a battle between two wolves. One is evil. It is hatred, greed, arrogance, malice. The other is kind. It is compassion, love, empathy, and truth.” The grandson asks, “Which wolf wins?” The wise grandfather replies, “the one you feed.”

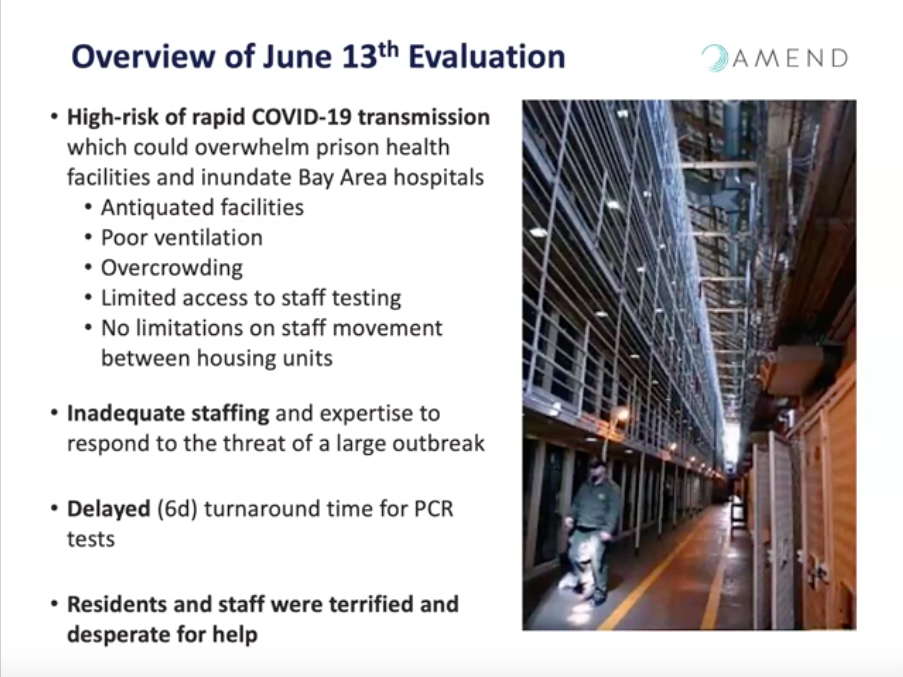

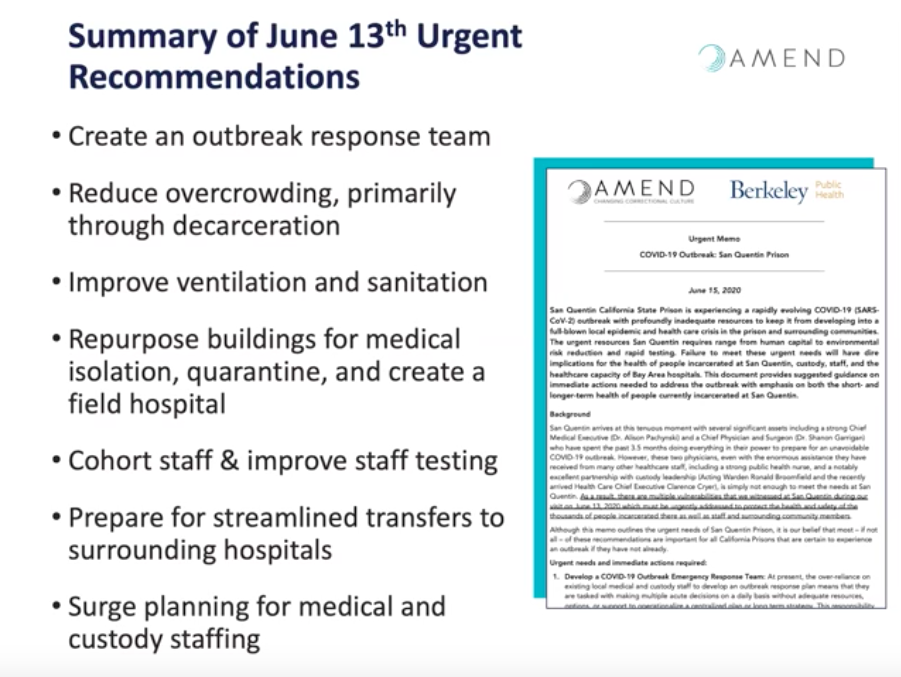

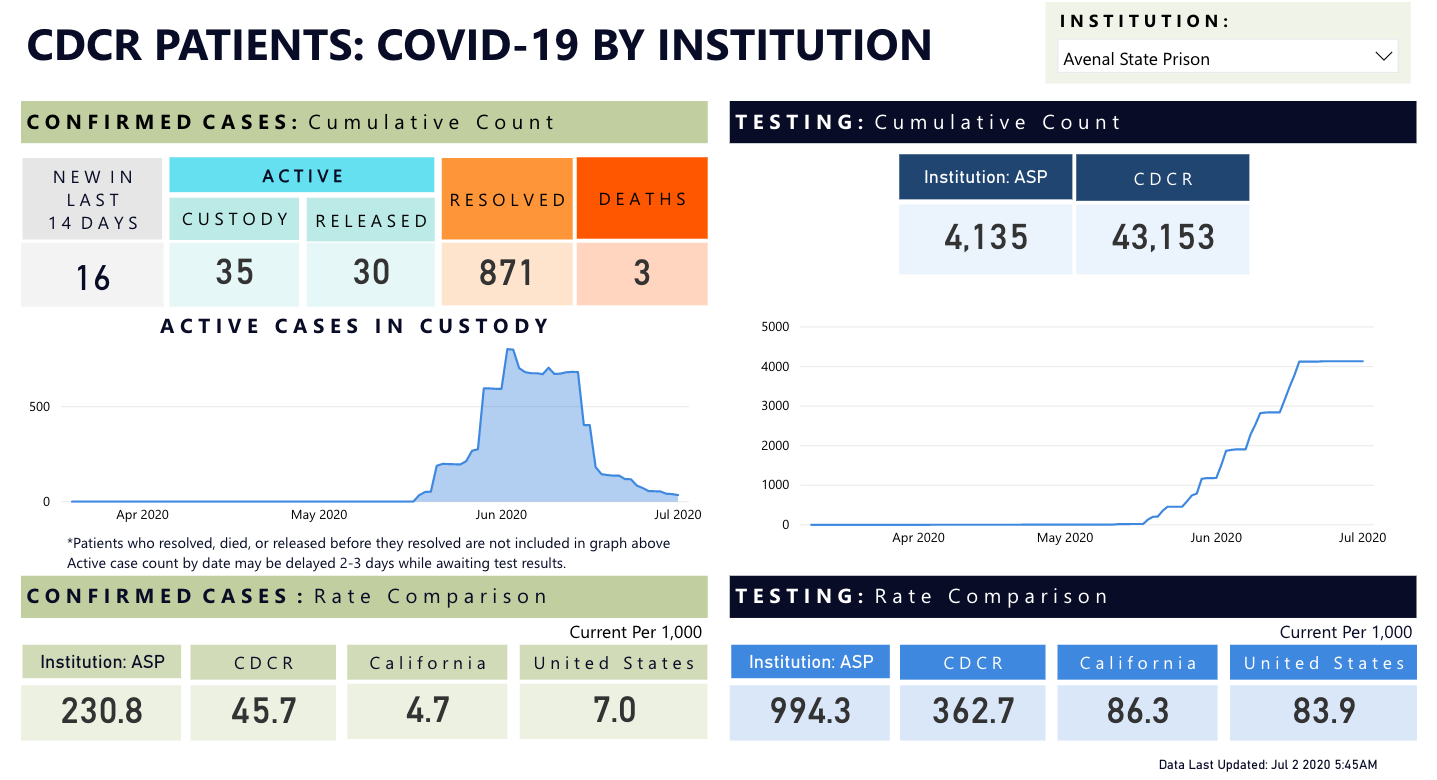

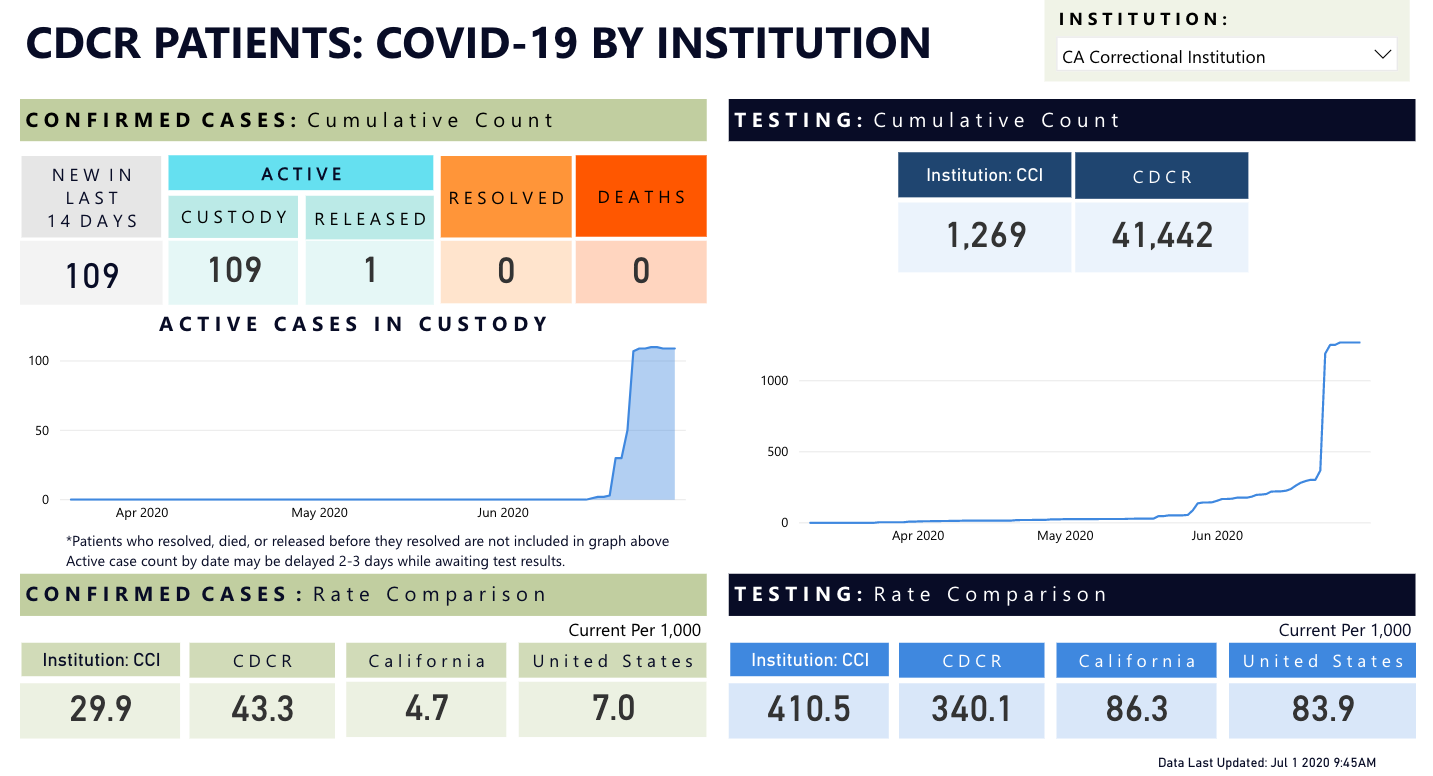

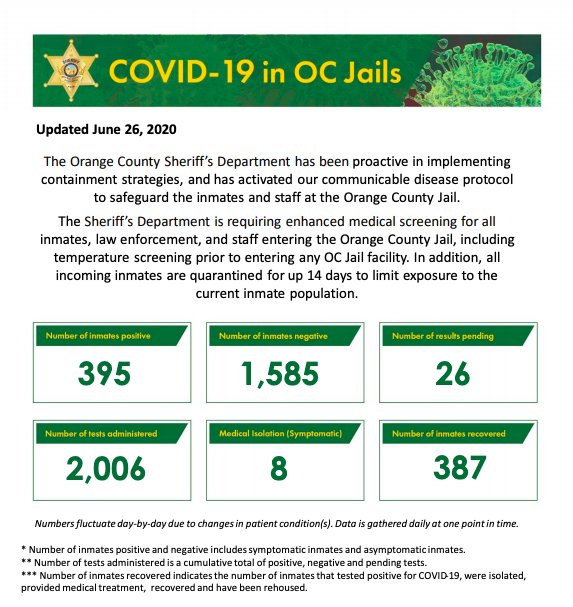

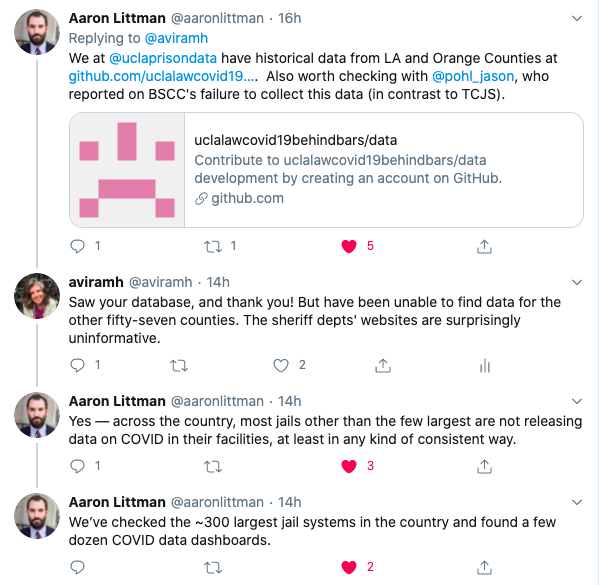

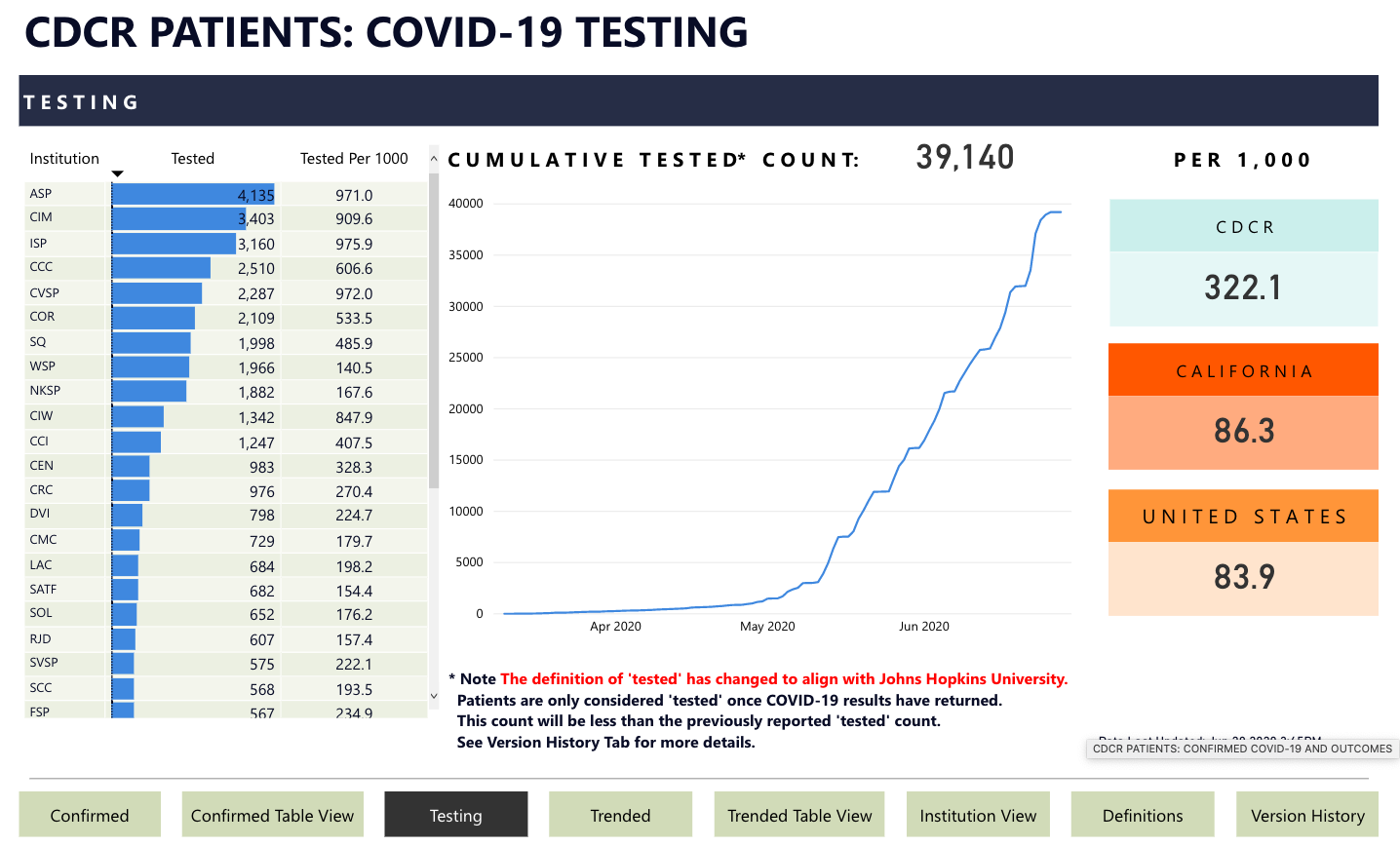

If Gov. Newsom were here, I would ask him which wolf he wants to feed. But he is not. Where is he? When people are getting sick and dying in droves, where is he? When buses transport people from prison to prison without testing and quarantining them, where is he? When people who test positive and negative are thrown together without care, where is he? When there is no retesting, where is he? When people get no medical treatment beyond checking their vitals, where is he? When people are terrified to report their symptoms out of fear that they will be thrown in death row or in solitary confinement, where is he? When we don’t even know what’s going on in jails and juvenile facilities because they are not reporting numbers, where is he?

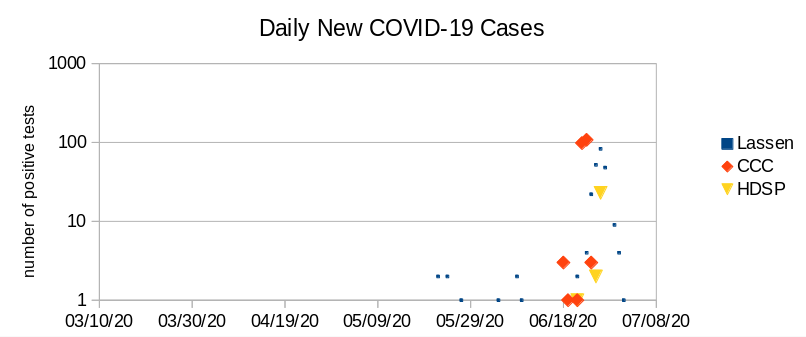

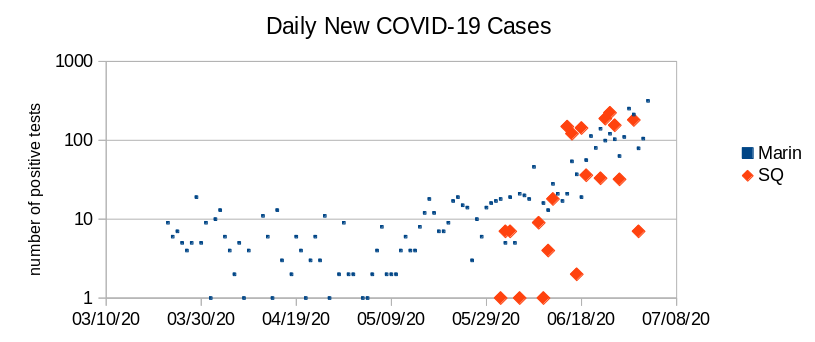

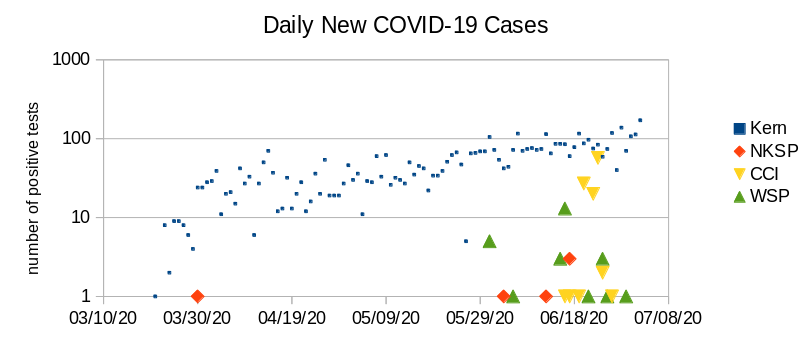

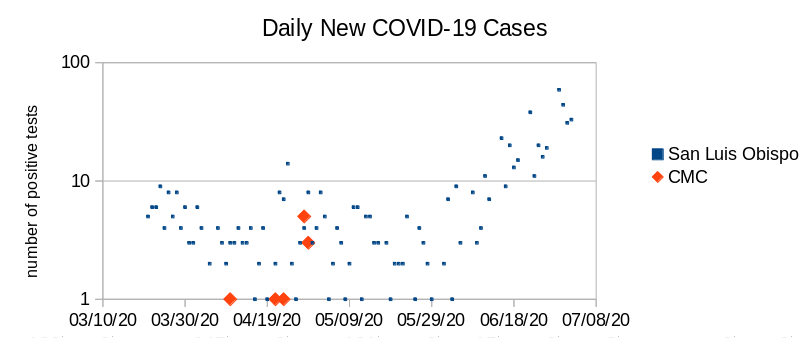

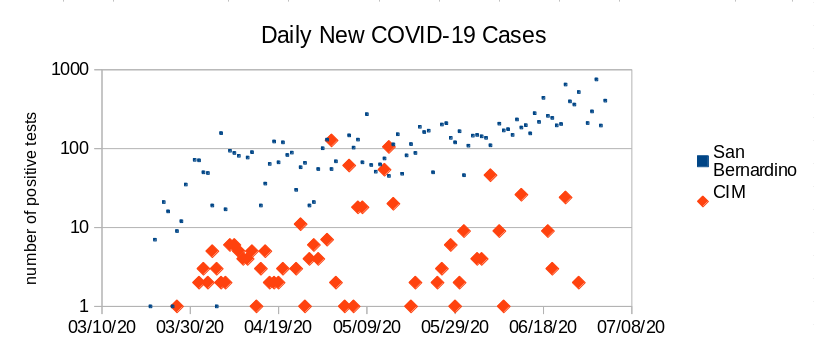

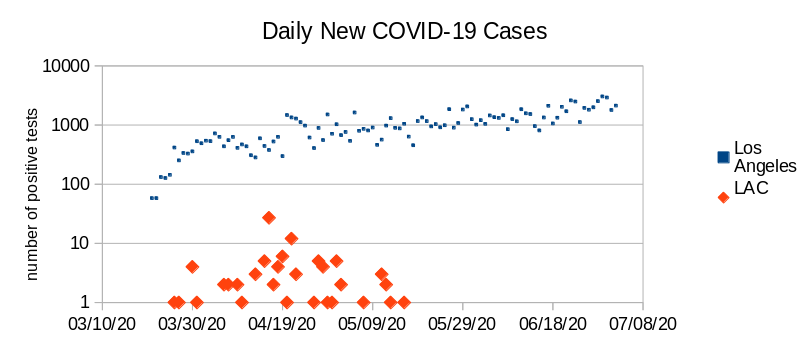

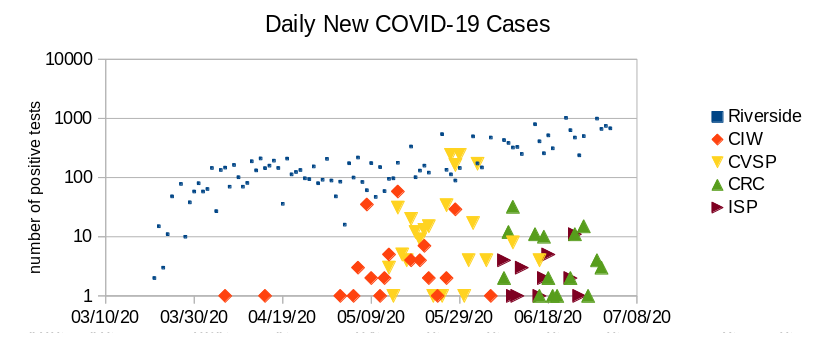

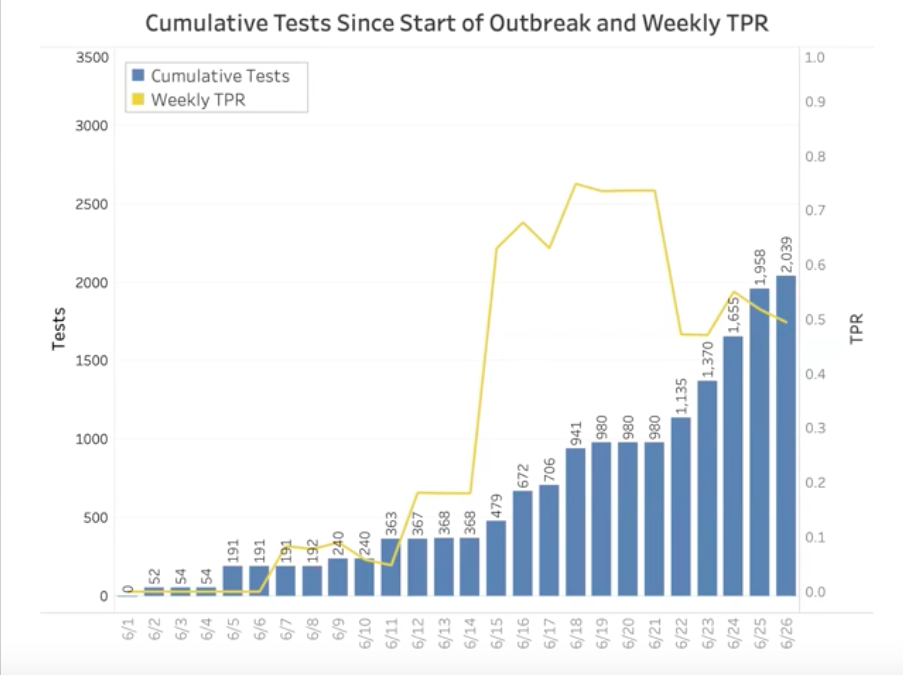

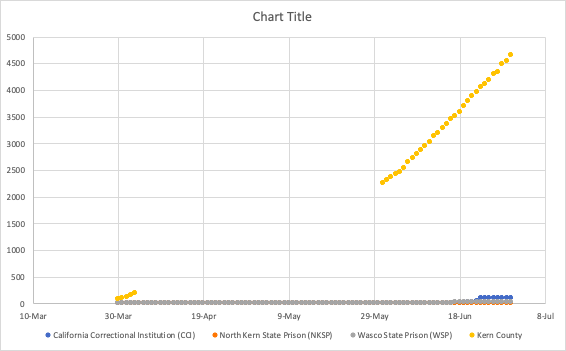

I know that many people secretly think that lives behind bars are worth less than lives on the outside. Some of this ignorance comes from the panic and cabin fever of the pandemic. I would like to explain to them that prisons are part of the community, and that people in prison are members of the community. I should know; I ran the numbers. Infection rates in Marin county spiked after the outbreak in San Quentin. Infection rates in Lassen county spiked after the outbreak in prisons in Susanville. Saving lives in prison is a priority because it protects everyone, people behind bars and people on the outside. By contrast, incubating the virus in prisons endangers us all and makes all our prevention efforts futile. You asked us to do our part. When will you do your part, Gov. Newsom? Which wolf do you want to feed?

The people behind these gates are serving sentences under the California Penal Code. They were not sentenced to abuse, neglect, and illness. They were not sentenced to chaos and ineptitude. They are in the custody of their government, and with this great power comes great responsibility. So, Gov. Newsom, which wolf do you want to feed?

Newspapers have been making distinctions between so-called “violent” and “nonviolent” people. I am here to tell you the facts. The facts are that a quarter of the California prison population are people aged 50 and older. These people do not pose a risk to public safety; rather, they themselves face risks because of their age and deteriorating health. My colleagues and I have studied California crime rates for decades and found no correlation between the crime and commitment and the risk of reoffending. The public risk here is not from imaginary crime, but from the very real possibility that our prisons are turning into mass graves. So, Gov. Newsom, which wolf do you want to feed?

We’ve had to release people from our bloated prisons twice recently: in 2011 and in 2014. Both times, there was fearmongering, and there were stories in the media. We let out tens of thousands of people. We know what happened because we crunched the numbers: Crime rates stayed low. Violent crime did not rise. There was no increased risk to public safety. So, Gov. Newsom, which wolf do you want to feed?

The virus is tearing through Death Row, and the irony is that California has a moratorium on the death penalty. For decades, we litigated to the tune of billions of dollars how to kill people in a way that was not “cruel and unusual”. We were even careful to examine whether people were healthy enough to be killed by the state. And so, when you put the moratorium in place, Gov. Newsom, we applauded you for doing the right thing for California. How does that feel now, when more people have died during this moratorium than we actually executed in the entire century? Which wolf do you want to feed?

Moreover, we know for a fact that some of the people behind these gates, whom you are sentencing to death via Covid, are innocent. They are behind bars because of mistaken eyewitnesses, coerced confessions, and hidden exculpatory evidence. So, Gov. Newsom, which wolf do you want to feed?

And we know that crimes are not just a matter of choice. They come from a confluence of factors, such as poverty, neglect, deprivation, abuse, racial discrimination, persecution, food deserts, lead poisoning, necessity, mental illness, substance abuse, pain and hurt and suffering. The virus doesn’t take sides. The virus doesn’t decide who “deserves” to get sick. So, Gov. Newsom, which wolf do you want to feed?

In 2005, at the UC Berkeley ceremony in which I received my Ph.D., you, then Mayor of San Francisco, were the commencement speaker. You spoke of your decision to allow people to marry the person that they loved. And you said that it is important to do the right thing, even if it’s politically risky, even if you face press backlash, even if people are not ready for it. History has smiled on your bravery. We applauded you for your courage. Now is just such a moment. History is being written, right now, behind these gates. You know the right thing to do. Trust your own goodness. Trust your own courage. Trust your own compassion. Bring them home.