Today the sages continue with their project of defining the rebellious son as narrowly as possible. Part of the biblical definition of a rebellious son includes the description זוֹלֵל וְסֹבֵא, which means excessively stuffing one’s face with food. The goal of today’s page is to provide the most outlandishly extreme benchmarks for eating, which made me think of a book I read last week: Jason Fagone’s excellent (and marvelously titled) Horsemen of the Esophagus.

Jason, currently an investigative reporter with the San Francisco Chronicle, is someone I like, admire, and respect a lot from back in the days that we were both at the front lines of the COVID-19-in-prison crisis. He was part of the team that broke the story about the San Quentin outbreak and was reporting heartwrenching stories that shocked and surprised even those of us who were on the phone every day with the people inside and their families. I therefore value not only his turn of phrase, but also his vast empathy and curiosity. And both of those qualities are in full display even in this earlier work. There would be nothing easier than to present competitive eaters as freakish and grotesque, or as dupes of crass marketing ploys, but Jason takes them and their project seriously, on their own terms; they are aware of the financial side of the enterprise and the health risks, but they treat what they do seriously, consider themselves athletes, and have a considerable part of their identities wrapped up in these competitions.

Some of the descriptions of food in this daf reminded me of Jason’s book, as will become immediately apparent. The starting point is the Mishna, which says:

מֵאֵימָתַי חַיָּיב? מִשֶּׁיֹּאכַל תַּרְטֵימָר בָּשָׂר, וְיִשְׁתֶּה חֲצִי לוֹג יַיִן הָאִיטַלְקִי. רַבִּי יוֹסֵי אוֹמֵר: מָנֶה בָּשָׂר, וְלוֹג יַיִן. אָכַל בַּחֲבוּרַת מִצְוָה, אָכַל בְּעִיבּוּר הַחֹדֶשׁ, אָכַל מַעֲשֵׂר שֵׁנִי בִּירוּשָׁלַיִם, אָכַל נְבֵילוֹת וּטְרֵיפוֹת שְׁקָצִים וּרְמָשִׂים (אָכַל טֶבֶל וּמַעֲשֵׂר רִאשׁוֹן שֶׁלֹּא נִטְּלָה תְּרוּמָתוֹ וּמַעֲשֵׂר שֵׁנִי וְהֶקְדֵּשׁ שֶׁלֹּא נִפְדּוּ). אָכַל דָּבָר שֶׁהוּא מִצְוָה, וְדָבָר שֶׁהוּא עֲבֵירָה, אָכַל כׇּל מַאֲכָל וְלֹא אָכַל בָּשָׂר, שָׁתָה כׇּל מַשְׁקֶה וְלֹא שָׁתָה יַיִן – אֵינוֹ נַעֲשֶׂה בֵּן סוֹרֵר וּמוֹרֶה עַד שֶׁיֹּאכַל בָּשָׂר וְיִשְׁתֶּה יַיִן, שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר: ״זוֹלֵל וְסֹבֵא״. וְאַף עַל פִּי שֶׁאֵין רְאָיָה לַדָּבָר, זֵכֶר לַדָּבָר שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר: ״אַל תְּהִי בְסֹבְאֵי יָיִן בְּזֹלְלֵי בָשָׂר לָמוֹ״.

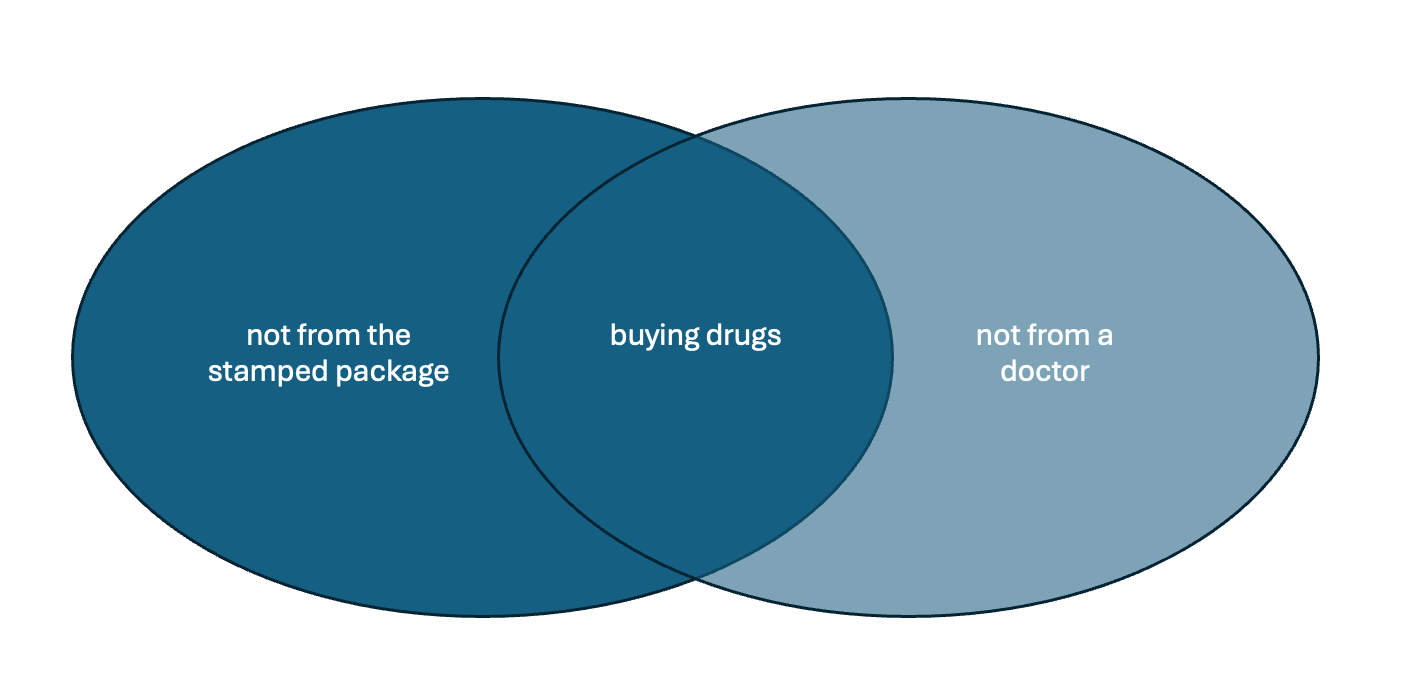

So according to the Mishna, to be a rebellious son you have to be a glutton in all the following ways: (1) eat both meat and wine, to the tune of (2) a tharteimar (?) of meat and (3) half a log of Italian (!) wine, (4) eat non-kosher things, (5) not eat in a group and (5) not eat something that is a mitzvah to eat. That doesn’t leave you with a lot of transgressive meals, so to rise to the level of a rebellious son it has to be a truly outrageous, over-the-top meal indeed. Can the Gemara sages top that?

How much meat and wine? Rabbi Zeira doesn’t know what a “tharteimar” is, but believes that since the wine amount is double what you expect someone to consume, it’s the same re the meat portion, and so a “tharteimar” is “half a maneh”.

What cost of meat and wine? According to Rav Huna, inexpensive stuff (paraphrasing Woody Allen–the food was so bad and the portions so big).

How should the meat and wine be prepared? Rav Hanan cites Rav Huna: raw meat and “live” (unstrained? undiluted?) wine. Others disagree and think eating these things is actually fine. Ravina proposes a compromise: medium-rare meat and improperly diluted wine. Rabba & Rav Yosef: eating salted meat is fine, as is drinking wine straight from the press (essentially grape juice). This last comment leads to a long segue about the kosher qualities of salted meat, how long is should be salted for, and how long the wine should ferment for (three days, says a baraita, which I think should surprise some friends in Napa and Sonoma).

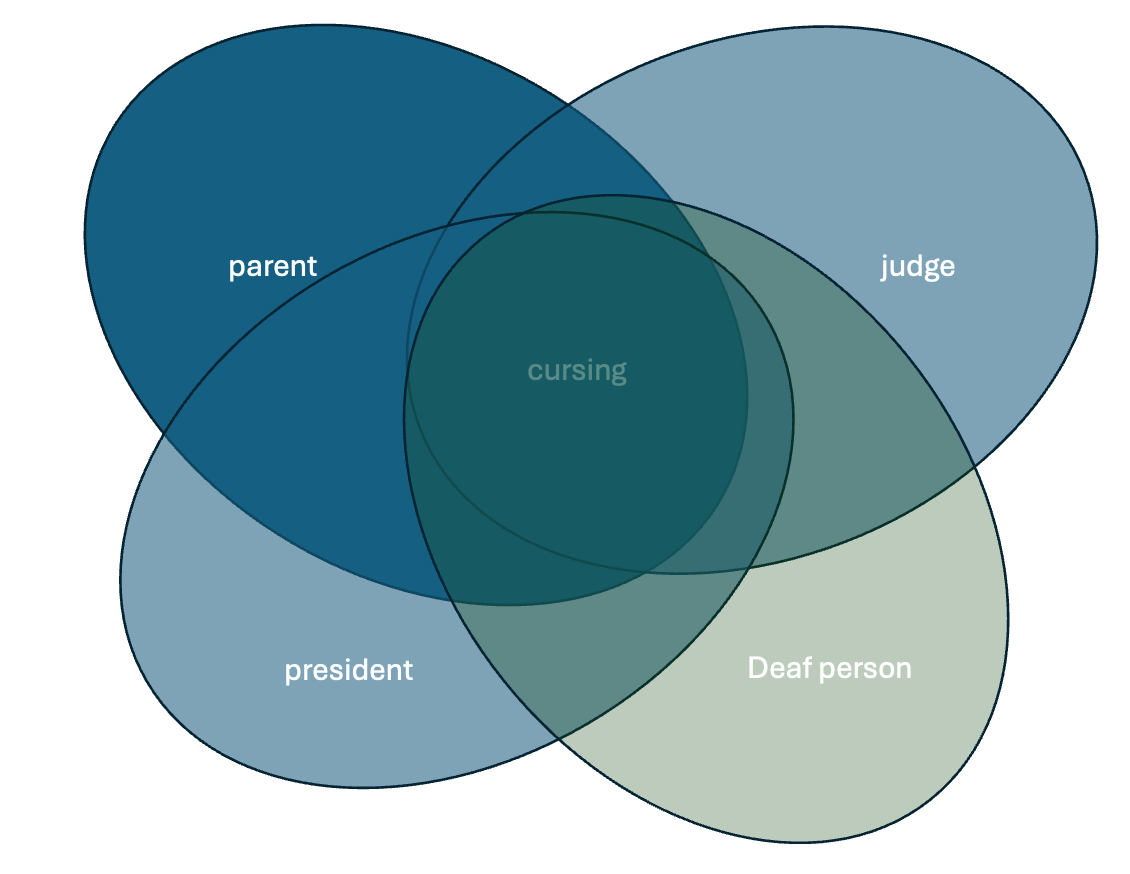

The concern with the rawness of the meat and wine has to do with what can and cannot be eaten on Tish’a be-Av, the memorial day for the destruction of the temple. But that discussion is a good springboard for a general round of commentary about the virtues of drinking in moderation. The various rabbis provide some zingers, with which you can charm everyone at your next pub crawl, champagne tasting, or AA meeting:

אָמַר רַב חָנָן: לֹא נִבְרָא יַיִן בָּעוֹלָם אֶלָּא לְנַחֵם אֲבֵלִים, וּלְשַׁלֵּם שָׂכָר לָרְשָׁעִים, שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר: ״תְּנוּ שֵׁכָר לְאוֹבֵד וְיַיִן לְמָרֵי נָפֶשׁ״.

Wine is for comforting mourners and paying the wicked (so that they rejoice in this world but not the next).

אָמַר רַבִּי יִצְחָק: מַאי דִּכְתִיב ״אַל תֵּרֶא יַיִן כִּי יִתְאַדָּם״? אַל תֵּרֶא יַיִן שֶׁמַּאֲדִים פְּנֵיהֶם שֶׁל רְשָׁעִים בָּעוֹלָם הַזֶּה, וּמַלְבִּין פְּנֵיהֶם לָעוֹלָם הַבָּא. רָבָא אָמַר: ״אַל תֵּרֶא יַיִן כִּי יִתְאַדָּם״ – אַל תֵּרֶא יַיִן שֶׁאַחֲרִיתוֹ דָּם.

Wine reddens the faces of the wicked and whitens it (with shame) for the next world.

רַב כָּהֲנָא רָמֵי: כְּתִיב ״תִּירָשׁ״ וְקָרֵינַן ״תִּירוֹשׁ״. זָכָה – נַעֲשֶׂה רֹאשׁ, לֹא זָכָה – נַעֲשֶׂה רָשׁ.

The term for sweet juice, tirosh, is a play on rosh (head) and rash (poor).

רָבָא רָמֵי: כְּתִיב ״יְשַׁמַּח״ וְקָרֵינַן ״יְשַׂמַּח״. זָכָה – מְשַׂמְּחוֹ, לֹא זָכָה – מְשַׁמְּמֵהוּ. וְהַיְינוּ דְּאָמַר רָבָא: חַמְרָא וְרֵיחָנֵי פַּקַּחִין.

The term “yesamah” (will gladden) can go either way: either you do become glad (mesamho), or you become desolate (meshamemehu)

אָמַר רַב עַמְרָם בְּרֵיהּ דְּרַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן בַּר אַבָּא, אָמַר רַבִּי חֲנִינָא: מַאי דִּכְתִיב ״לְמִי אוֹי לְמִי אֲבוֹי לְמִי מְדָנִים לְמִי שִׂיחַ לְמִי פְּצָעִים חִנָּם לְמִי חַכְלִלוּת עֵינָיִם (וְגוֹ׳) לַמְאַחֲרִים עַל הַיָּיִן לַבָּאִים לַחְקֹר מִמְסָךְ״? כִּי אֲתָא רַב דִּימִי אֲמַר: אָמְרִי בְּמַעְרְבָא, הַאי קְרָא מַאן דְּדָרֵישׁ לֵיהּ מֵרֵישֵׁיהּ לְסֵיפֵיהּ – מִדְּרִישׁ, וּמִסֵּיפֵיהּ לְרֵישֵׁיהּ – מִדְּרִישׁ.

Wine is associated with fighting and injuries and red eyes.

דָּרֵישׁ עוֹבֵר גָּלִילָאָה: שְׁלֹשׁ עֶשְׂרֵה וָוִין נֶאֱמַר בַּיַּיִן: ״וַיָּחֶל נֹחַ אִישׁ הָאֲדָמָה, וַיִּטַּע כָּרֶם, וַיֵּשְׁתְּ מִן הַיַּיִן, וַיִּשְׁכָּר, וַיִּתְגַּל בְּתוֹךְ אׇהֳלוֹ, וַיַּרְא חָם אֲבִי כְנַעַן אֵת עֶרְוַת אָבִיו, וַיַּגֵּד לִשְׁנֵי אֶחָיו בַּחוּץ, וַיִּקַּח שֵׁם וָיֶפֶת אֶת הַשִּׂמְלָה, וַיָּשִׂימוּ עַל שְׁכֶם שְׁנֵיהֶם, וַיֵּלְכוּ אֲחֹרַנִּית, וַיְכַסּוּ אֵת עֶרְוַת אֲבִיהֶם וּפְנֵיהֶם וְגוֹ׳״, ״וַיִּיקֶץ נֹחַ מִיֵּינוֹ, וַיֵּדַע אֵת אֲשֶׁר עָשָׂה לוֹ בְּנוֹ הַקָּטָן״.

One example of the harms of drinking too much is Noah, whose nakedness was witnessed by his youngest child after he blacked out in his tent. This, by the way, leads to a side discussion about what, precisely, the youngest child did, which we’ll leave out of this. But at least Rabbi Zakai–and possibly also Rabbi Meir connects Noah’s misfortune to the banishment of Adam from Heaven, which he blames on wine (a dispute erupts on whether the infamous tree in Eden was a vine).

שֶׁאֵין לְךָ דָּבָר שֶׁמֵּבִיא יְלָלָה לְאָדָם אֶלָּא יַיִן.

Wine brings about wailing.

In what company? Rebellious sons eat in the company of empty nothings (סְרִיקִין). According to the sages, even if there are some worthy companions, if they are gathered for idle purposes, the rebellious son is still liable.

What’s the timing of the meal? During the full moon, there’s a celebratory meal (to which you’re supposed to arrive at daybreak) with only grains and legumes. But if the rebellious son eats meat and wine there, he’s at least participating in the ritual, so it doesn’t count. Similarly, if the meal is a second tithe in Jerusalem, it’s fine.

What sort of meat? Chicken is fine, according to Rava; insects and creepers are not. But Rava speaks of diet generally, rather than on the excessive addition of bad foods. Transgressive food in itself does not render one a rebellious son, because the essence of the offense is disobeying one’s parents, rather than God.

Meat- and wine-analogues? The rabbis argue that it has to be actual meat and actual wine. Drinking other intoxicating things, like honey and milk, doesn’t count. Also, eating other filling things, like dried figs, does not count.

So, you see, these are very specific, peculiar ways to binge and overindulge; your regular bingeing and overindulgence do not land you in biblical trouble. We will continue to see these narrow interpretations in the next few days.