Like Episode 8, Episode 9 deals with issues of race and racism within the police force, this time through the story of Joe Moran, who, unbeknownst to his wife, kids, and fellow officers, is Cuban. Having benefitted from the ambiguity in his last name, Moran persuasively convinced his wife that he was Irish, and advanced through the ranks, until… a Latino journalist, Sandoval, found out the truth and decided to “out” Moran as Cuban.

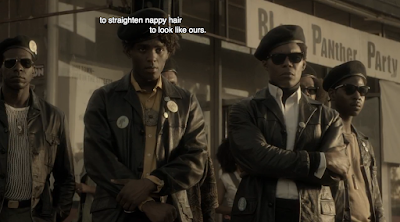

Moran’s fear that his wife will leave him leads him to attempt suicide, and Hodiak, who comes into the room, tries to help. He reveals to Moran that his father was Jewish, a fact that he also does not share widely in the department. It’s understandable why: in both episodes, the idea of affirmative action or of representation of women or “spics” is considered ridiculous. There’s not, I should mention, a black officer in sight.

Moran and, to a lesser degree, Hodiak, are examples of the quiet tragedies of “passing” and living a lie, which are echoed by the series’ exposure of sexual and marital hypocrisies. Moran reminds me a bit of Silk, the hero of Philip Roth’s novel The Human Stain, which is based on the life of Roth’s friend, Melvin Tumin.

Moreover, Moran reminded me of Osagie Obasogie’s recent book Blinded by Sight, in which he problematizes the idea that race is something that is “seen” by interviewing people who have been blind since birth about their experiences of race. The interviewees told Obasogie something fascinating: like seeing people, blind people experience race visually. Race is, therefore, not something that just “is” (Obasogie calls this faulty assumption “‘race’ ipsa loquitur“) but something that is created, manufactured, as presumably visual.

In one of the book’s vignettes, Obasogie tells an incredible, and horrible, tale of a trial for marriage fraud. The story is so astounding that I quote it in its entirety:

Leonard Rhinelander was the socialite son of a wealthy New York family. In the fall of 1921, he met Alice Jones through her sister Grace and the couple quickly became quite fond of each other. On at least two occasions during their first few months together, the couple–Alice was then twenty-two, four years Leonard’s senior–secluded themselves for days in New York City hotels where they were intimate. Over the next few years, Leonard took several extended trips at his father’s request that separated the couple, but they remained in touch through frequent letters proclaiming their love for one another. Leonard returned to New York in May of 1924, and the couple secretly married that October, as Leonard’s family was not fond of the former Ms. Jones. The couple lived in secret with Alice’s family for about a month, until a story appeared in the Standard Star, a local paper in New Rochelle, titled: “Rhinelanders’ Son Marries the Daughter of a Colored Man.” Thus, a wealthy White man from 1920s New York high society was exposed as having committed one of the biggest social faux pas one could imagine at the time: marrying a Black woman.

Alice was the biracial daughter of an English mother and a father described as “a bent, dark complexioned man who is bald, except for a fringe of curly white hair.” A few days after the story broke, Leonard was shown a copy of Alice’s birth certificate that documented her race as Black. Two weeks later, Leonard filed suit for an annulment. The reason? Fraud: Leonard alleged that Alice misrepresented that she was not colored to trick him into marrying her. The stage was now set for what some might characterize as, up until then, the race trial of the century: a legal determination of whether Alice committed fraud by “passing” as White or if Leonard knew Alice’s race before their marriage. Put differently, the question became what did Leonard know and, more importantly, what should he have known?

The strategy developed by Isaac Mills, Leonard’s attorney, portrayed him as mentally challenged and Alice’s physical features as racially ambiguous. The defense from Alice’s counsel, Lee Parsons Davis, was quite simple: there was no fraud as Alice’s blackness was visually obvious. Davis mockingly said to the jury:

I think the issue that Judge Mills should have presented to you was not mental unsoundness but blindness. Blindness . . . [Y] ou are here to determine whether Alice Rhinelander before her marriage told this man Rhinelander that she was white and had no colored blood. You are here to determine next whether or not that fooled him. Whether or not he could not see with his own eyes that he was marrying into a colored family.

After raising serious doubts about Leonard’s cognitive disability, much of Davis’ defense rested on showing that Alice’s race could be known by simply looking at her body. This became a central theme in Davis’ argument; he repeatedly asked Alice and her sisters to stand up and show the jury their hands and arms. But to hammer home this point, Davis wanted the jury to see all of Alice’s body–not just hands and arms that might darken over time with routine exposure to sunlight. Given the couple’s pre-marital relations, Davis argued that Leonard had seen all of Alice before being married, and that it was crucial for the jury to see the same intimate details of Alice’s body that Leonard did before marrying her. Against objections from Leonard’s attorneys, the judge allowed it. And what transpired was one of the biggest race spectacles of the twentieth century. From the Court record:

The Court, Mr. Mills, Mr. Davis, Mr. Swinburne, the jury, the plaintiff, the defendant, her mother, Mrs. George Jones, and the stenographer left the courtroom and entered the jury room. The defendant and Mrs. Jones then withdrew to the lavatory adjoining the jury room and, after a short time, again entered the jury room. The defendant, who was weeping, had on her underwear and a long coat. At Mr. Davis’ direction she let down her coat, so that the upper portion of her body, as far down as the breast, was exposed. She then, again at Mr.Davis’ direction, covered the upper part of her body and showed to the jury her bare legs, up as far as her knees. The Court, counsel, the jury and the plaintiff then re-entered the court room.

This dramatic revealing of Alice’s body to the jury composed of all White married men was stunning, especially for 1920s sensibilities. Once back in the courtroom, Davis asked Leonard, “Your wife’s body is the same shade as it was when you saw her in the Marie Antoinette [hotel] with all of her clothing removed?”Leonard responded affirmatively, to which Davis said “That is all.” Shortly after this display of Alice’s body to the jury and Leonard’s acknowledgement, the jury returned with a verdict in favor of Alice, finding that there was no fraud. To put a finer point on this: an all White male jury in 1925 ruled against a wealthy White male socialite and in favor of a working class Black woman because her race was found to be so visually obvious that there could have been no deception. The jury found that Alice’s body, and race in general, visually spoke for itself. Alice did not have to take the stand at any point during the trial. Her body, and the jury’s ability to observe it, was all of the evidence that was needed.

Joe Moran’s story is a televised representation of the lives of many people, such as Alice Jones, whose racial identity had to be constructed as “seen”. And it is a sobering reminder that, as late as the late 1960s, there were still people who were embarrassed and terrified to openly acknowledge their racial identities.