Two friends, young, poor, bright, and full of promise, sit together in a shabby room in Warsaw. They are joyous, for not only do they have food and oil to light the furnace—a rare occurrence—but also a fresh-from-the-presses literary journal issue, containing a new poem by a famous poet they both admire. They recite the poem to each other, squealing, frolicking, then leap into each other’s embrace, as the fire burns in the furnace and a candle flickers on the table.

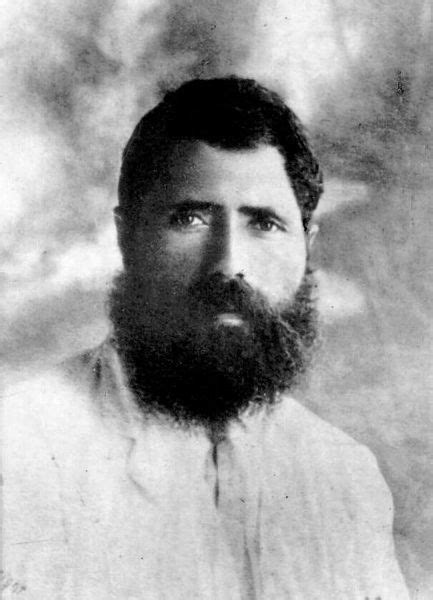

The two young men were Yosef Haim Brenner, among the most celebrated and appreciated Hebrew revival novelists and essayists, and Uri-Nissan Gnessin, a master of the short story in Hebrew and Yiddish. Intimate friends since their yeshiva days under the tutelage of Gnessin’s father in Pochep, Ukraine, the two ended up at the frontlines of literary innovation in Hebrew. They traveled across Europe fighting poverty and shirking military service. Brenner ended up living in a shabby room in East London, working long hours as a typesetter to fund his passion: his literary journal Ha’Meorer (“The Awakener”), a serial publication of Hebrew fiction, essays, and poetry. Gnessin edited Nisyonot (“attempts,”) a periodic collection of short stories. In 1907, after much deliberation, Gnessin joined Brenner in London, but the friends’ attempt at a shared life went sour within a few weeks and the two broke all contact. Brenner immigrated to Eretz Israel (then part of the Ottoman empire) in 1909 and, after a short and unsuccessful attempt at agricultural labor, moved to Jaffa and resumed his intellectual and creative career, venerated by members of the Yishuv for his originality and creative genius despite frequent controversies stemming from his controversial, strident writing. Gnessin returned to Pochep and in 1912 moved to Warsaw, already gravely ill with a congenital heart condition, a fact unknown to Brenner and to most, or all, of their circle of friends. On his deathbed he cried out Brenner’s name. The year was 1913, Gnessin was 33 old at his death, and when Brenner heard of Gnessin’s death, he was devastated. His moving eulogy to his intimate friend, “Uri-Nissan: A Few Words,” is at the heart of this paper.

Brenner married and fathered a child, whom he named Uri-Nissan and doted on, but divorced while his son was an infant. He then rented a room at a ranch in the outskirts of Jaffa, where he mentored an unknown young author, Yosef Luidor, and invited Luidor to live with him. In 1921, during a horrific pogrom in Jaffa, Brenner and several other authors, including Luidor, were horrifically brutalized and murdered at their lodging. The crime scene was so heinous, and reflected such atrocious slaughter and torture, that details were kept confidential even as the murder filled newspaper headlines, and many of the facts remain unknown to this day.

While Brenner’s books and essays are still regarded as the pinnacle of artistic merit in the Hebrew language, and his many novels, including his final masterpiece Skhol VeKishalon (“Bereavement and Failure”), are cited as inspiration by many Israeli literary giants, his works are no longer widely read beyond a small circle of literature connoisseurs. But in recent years, there has been a surge of interest in, and controversy around, Brenner—not for his literature and ideology, but for his personal, romantic, and sexual life.

The two works that sparked these controversies were literary critic Menahem Perry’s nonfiction work Sit on Me and Warm Up: The Homoerotic Dialogue of Brenner and Gnessin (Tel Aviv: The New Library, 2020), and novelist Alon Hilu’s speculative novel Murder at the Red House (Tel Aviv: Yediot, 2018). Perry’s book painstakingly recreates Brenner and Gnessin’s London misadventure, whereas Hilu’s book offers a shocking, lurid narrative that casts the murders of Brenner and Luidor as stemming from a doomed homoerotic triangle. The turmoil and heat generated by both books is the subject of this paper.

My interest is not in the was-he-or-wasn’t-he question; there is plenty in Brenner’s tortured personal life to suggest that he was a complicated man, and as to his suspected and confirmed romantic entanglements, we know that some were tragic (Gnessin), some tender (Luidor), and some, as we will see, unsavory, especially to a 21st century reader. We also know that Brenner was plagued by debilitating mental illness—perhaps depression, perhaps bipolar disorder—and it is not a stretch to hypothesize that his emotional suffering was related at least in part to his unconventional sexuality, as well as to the fact that such sexual feelings and desires, though certainly present and not uncommon, were deeply stigmatized and unspoken among the halutzim and absent from public discourse in Israel until the 1960s. What I do wonder about is the sudden cultural appetite for the sexual and romantic entanglements of a man murdered more than a century ago: What, beyond prurience, can explain this recent interest in Brenner’s sexuality? Does the speculation, investigation, and debate regarding Brenner’s queerness contribute to our understanding of his work or his death, and if so, how?

Perry’s Sit On Me and Be Warm: Investigating and Reading Between the Gaps

Most serious Brenner biographers unflinchingly accept that Gnessin was his first and biggest love interest, and that the relationship, as well as Gnessin’s premature death, deeply impacted Brenner’s life and work. You can see some of these comments in Yair Kedar’s terrific documentary HaMeorer (2016), a beautiful film I recommend you watch in its entirety:

Shai Zarhi comments:

Gnessin was truly the love of his life; I really do think he was the love of his life. They emerged together and they started writing together. You know, they went through formative experiences together, that create a friendship… a very big love. And with difficulty, because both of them were very complicated people.

The most harmonious and idealized expression of this relationship is an episode described in Brenner’s eulogy for Gnessin (1913), which centers around a poem by Haim Nahman Bialik titled “On a Sunny, Warm Day.” The poem proceeds in three parts, corresponding to three seasons. In the first, the narrator joyously a friend (“pleasant brother,” “blessed of God”) to his garden during the hot summer months. The second part, which is especially relevant to Perry’s inquiry, reads:

When the black cold of a winter’s night

bruises you with its icy pinch

and frost sticks knives in your shivering flesh,

then come to me, blessed of God.

My dwelling is modest, lacking splendor,

but warm and bright and open to strangers.

A fire’s in the grate, on the table a candle –

my lost brother, sit with me and get warm.

When we hear a cry in the howling storm

we will think of the destitute starving outside.

We will weep for them – honest pitiful tears.

Good friend, my brother, let us embrace.

וּבְלֵיל חֹרֶף, לֵיל קֹר, עֵת מַחֲשַׁכִּים וּשְׁחוֹר

יְשׁוּפוּךָ בַּחוּץ, הוֹלֵךְ סוֹבֵב הַקֹּר,

וּבִבְשָׂרְךָ כִּי-יִתְקַע מַאַכְלוֹתָיו הַכְּפוֹר –

בֹּא אֵלַי, בֹּא אֵלַי, בְּרוּךְ אֲדֹנָי!

בֵּיתִי קָטָן וָדַל, בְּלִי מַכְלוּלִים וּפְאֵר,

אַךְ הוּא חָם, מָלֵא אוֹר וּפָתוּחַ לַגֵּר,

עַל-הָאָח בֹּעֵר אֵשׁ, עַל-הַשֻּׁלְחָן הַנֵּר –

אֶצְלִי שֵׁב וְהִתְחַמֵּם, אָח אֹבֵד!

וּבְהִשָּׁמַע מִילֵל סוּפַת לֵיל קוֹל כָּאוֹב,

זָכֹר נִזְכֹּר עֱנוּת רָשׁ גֹּוֵע בָּרְחוֹב,

וּלְחַצְתִּיךָ אֶל-לֵב, רֵעִי, אָחִי הַטּוֹב –

וּרְסִיס נֶאֱמָן אוֹרִידָה עָלֶיךָ

In the third part of the poem, however, describing the fall season, the narrator wishes for solitude, begging his “merciful brother” to leave him alone, away from others’ prying eyes.

In his eulogy for Gnessin, Brenner reminisces about an evening in Warsaw, in which Gnessin returned from the printer with a fresh copy of the literary journal Luah Ahiasaf, containing the poem’s first-ever appearance in print, on an auspicious evening “when we had bread, tea, oil for the lamp, a warm fireplace.” By this time, Brenner and Gnessin were 19 and 21 years old, respectively, both out of the yeshiva and living secular lives. Brenner describes what happened next:

We sat, both of us, during dinner, and began: “On a warm, sunny day, when high noon makes the sky a fiery furnace and the heart seeks a quiet corner for dreams”, etc., etc., – a song by H. N. Bialik!- and after a little while, when we finished our meal, we already stood facing each other, knowing the poem by heart.

“A shady carob tree grows in my garden” – he emphasized every word with a sensuous, physical pleasure…

“And when the black cold of a winter’s night” – I extended a howl toward him…

“My dwelling is modest, lacking splendor” – he squealed, frolicking, and in his frolic “sat on me and got warm” while reciting “sit on me and get warm,” intoned “a cry in the howling storm,” imitated, with extended limbs, a “destitude starving outside,” jumped, shook, and then “pressed me to his heart,” his “brother, good friend” –

And suddenly –

The tear that had been sent in the letter from Pochep to Bialistok sparkled in his eye, and then another dropped –

“honest, pitiful tears,

Friend of my youth!”

Our bones shook, and in the furnace a fire burned, and on the table the candle…

Brenner’s description of the evening suggests harmony and mutuality, and his heartbreak over the rift with Gnessin is evident. Gnessin, however, never shared his own perspective on his relationship with Brenner, and though his biographer Anita Shapira observes that he sometimes expressed disgust with his friend, she still believes that they were “two opposites attracted to each other: Gnessin, tall, handsome, the Rabbi’s son, and Brenner, the plebeian, short, somewhat fat.” Shai Zarhi describes Gnessin as “completely different from Brenner. He was fastidious, delicate, a prince. But Gnessin’s special sensitivities, which created this deep connection—they were both people who were very sensitive to the soul.”

Perry’s resulting literary investigation led him to posit a much darker, unsavory picture of the relationship, which Perry links to a cynical interpretation of Bialik’s poem. In a nutshell, Perry sees “On a Sunny, Warm Day” as a prime example of a typical Bialik semiotic device, which Perry refers to as a “reversing poem.” In such a poem, readers are led to interpret the song in a certain way, only to find themselves confronted, later in the poem, with new, contrasting information that sheds a new light on the earlier part. Perry believes that, in “On a Sunny, Warm Day,” this mechanism plays out to reverse our opinion of the protagonist’s desire to commune with his friend, suggested by the first two sections: the summer and the winter. When we discover that, in the fall, the protagonist wishes for solitude and distance, it casts doubt and undermines the credibility of his previously expressed enthusiasm for companionship and intimacy.

Perry believes that Bialik’s reversing song is the key that unlocks Brenner and Gnessin’s relationship and also explains the rift that tore them apart during Gnessin’s stay in London, which is evident from Brenner’s words of despair in his friend’s memory:

Neither him nor I expected anything from his arrival in London, and nevertheless we were both as if cheated… as if we both had hoped that our meeting would be different, that our relationship would be different, that our lives together would be different.

And sometimes I thought: Everyone speaks of suffering. The word suffering is carried on every tongue. About us, as well—we are sufferers. Hebrew authors, exiles in East London, sickly, poor, etc. etc. But what could people know about the measure of suffering of this relation, that is between me and Uri-Nissan, my Uri-Nissan…

In the few good moments, of which there certainly were some then, hearts were joined and purified from the impurities of resentment. Then we both understood, that I am not at fault, that he is not at fault, that we are not at fault, only disaster lies upon us.

What was the “disaster”? To reconstruct those few fateful weeks, Perry engages in a maximalist reading of all documentary evidence of the London weeks, looking for details neglected or ignored by prior biographers, and “raising the concentration level” of the information about the relationship amidst the less important clues. He doggedly pursues clues in Gnessin’s letters to Brenner and others, painstakingly reconstructs the friends’ respective lodgings and employment situations in Whitechapel, and even travels to London to walk their paths and verify the feasibility of their intentional and accidental meetings. The resulting portrayal is one of a relationship that those of us inclined toward couples’ therapy (though not Perry) would easily armchair-diagnose as “anxious-avoidant.״ Gnessin, Perry believes, was always conflicted about his relationship with Brenner, fearful of him, and repelled by his exaggerated mannerisms and aggressive pursuit. His known romantic entanglements were with women, whom he treated shallowly and callously, and he teased Brenner with the same ambivalence that he teased some of his female lovers, including Yiddish poet Celia Drapkin, who attempted suicide after Gnessin rejected her. Perry documents Brenner’s repeated pestering and supplications that Gnessin, who was traveling throughout Europe, join him in London. After several evasions, Gnessin finally arrived in London in 1907, and during his stay there, for a few weeks shared close quarters with Brenner. Perry’s detective work suggests that the two shared not only a room, but a bed, and he hypothesizes that they also shared sexual intimacy. The experience was far from mutual and short-lived. Gnessin fled Brenner, quickly found a female lover and moved in with her, and never spoke to Brenner again. Perry carefully analyzes one of Brenner’s letters, in which he recalls walking to a public park and bitterly weeping there, and literally follows in Brenner’s footsteps in London, concluding that Brenner walked across the entire city to see Gnessin, who at this time lodged as far away from him as possible.

Casting Gnessin as the solitude-seeking narrator of the “autumn” section of Bialik’s poem, Perry shows that, at the time of his London visit, Gnessin was already aware of his congenital heart disease and his impending death. It was due to this heavy emotional burden that Gnessin shied away from deep connections and commitment, and his disease was known to no one (Perry mines the autobiography of Asher Beilin, who lived near Gnessin and Brenner in London, and finds Beilin’s assertions that he knew of Gnessin’s disease unreliable.) Brenner’s deep grief at Gnessin’s passing, Perry surmises, stems from the fact that he finally understood the source of his beloved’s avoidance and hostility, and agonized over having judged him and snapped at him. In particular, Perry is attentive to an anecdote Brenner describes in the eulogy: Gnessin, who worked as a typesetter for Brenner’s journal Ha’Meorer, made a typographic error, and in Brenner’s apology for the late publication, set the editor’s note to read, instead of “please accept it [the issue] with my apologies,” “please accept me with my apologies.” Brenner’s recollection of how he fumed at Gnessin for the error is impregnated with guilt and anguish, and Perry believes that this might have been Gnessin’s subconscious effort to apologize to Brenner for his rejection, an effort that Brenner recognized only posthumously.

Sit On Me and Be Warm became a lightning rod in the literary world. Perry is a venerated professor of Hebrew literature, the author of countless articles and essays, and the editor of several prestigious book series, and most of Israel’s literary circle consists of his former students. This hegemony has antagonized people who believe that their lack of fealty to Perry has harmed their careers, and that his work is unserious, as he is coasting on his earlier successes and established reputation. One of these critics, Ha’aretz literary critic Orin Morris, refers to Perry’s book as an “abject failure” (2017), and writes:

This could have been an excellent book, had Professor Perry striven to do what is expected of a reasonable biographer. That is, to make do with existing materials. Instead, Perry decides to play the part of a detective, but he has to invent a mystery, because a mystery does not exist here at all, but Perry cannot let go of the glory of a land discoverer, even in a world in which all continents have been already found for quite some time. That’s why validating the mystery is so full of effort, puffing, and sweating.

Morris rejects Perry’s “fanciful” interpretation of the Bialik poem as negating Gnessin’s attraction to Brenner. But more importantly, he expresses reservations about Perry’s project at all:

[Brenner’s] ambiguous sexuality is among the most open secrets of Hebrew literary gossip. What was he? Celibate, monastic, shy, horny, a latent homosexual, a friend to children—what difference does it make. Like any person, he had an assortment of desires and abhorrences, and like any person, his sexuality was mostly his own business. Perhaps he tried to put order into his excitement over the touch of Gnessin, who was a known seductor. Perhaps, but that is not grounds for a book, and certainly for this kind of book. . . in addition, about a century after the acceptance of Freudian theory, we can easily leave the following question open: if any lengthy, strong male friendship, a youth friendship, carries the echo of homoerotic secrecy, what is the sensation here?

A few days later, an irate Perry responds, also in a Ha’aretz article:

Morris’ critique completely misses the quality of the story I’m telling, a story that I by no means claim to be true and final. The intellectual adventure in the book—which describes a multistage love story and not the story of acts, a story that centers a Bialik song and a famous typographical error. . . provides hypotheses justified by the fact that they accommodate an ocean of details that were either neglected or marginalized or unknown before, and allow them to coalesce. To undermine this narrative suggestion one has to propose a better counterstory, or to explain why this standard for deciding between stories—by examining them and comparing their capacity to make meaning of details that were left neglected in other readings—is farfetched.

Yehuda Vizan’s ferocious critique of Perry’s work is of a different nature, and is titled “the fall of a giant”—referring, of course, not to Brenner, but to Perry himself:

There’s an especially aggressive academic fad here, an additional layer to the “discourse,” not to say neoliberal propaganda masquerading as literary research, the fruit of French fornication that became further contaminated in the United States, and arrived here to us, unenlightened savages that we are, with fashionable tardiness—in which scholars compete, perhaps with homoerotic pleasure—whose is bigger, that is, who has identified a bigger author in whose work, or letters, or a note on the fridge of his former neighbor, there is a hint, vague as might be, that he considered flipping the table, or perhaps did not, but would have liked to. Or maybe did not consider, or wish to, but dissociated with all his might his homoerotic fleshly desires, which might explain his antipathy toward women in his adult life, and circularly then proves the homoerotic tone of his works, etc.

Vizan is especially incensed by the fact that Perry himself, in an interview he gave to Vizan a decade earlier, decried the identitarian-ideological turn in literature and literature scholarship, complaining that ideology and gender theory “have nothing to do with literature” and are selectively deployed for the purpose of confirming theories of academics. He wonders about Perry’s megalomania and apparent change of heart about identitarianism, asking, “why, of all the topics in the world, would a liberal, Tel Avivi, enlightened author, in 2017, in the Eighth decade of his life, choose to write about “the homoerotic dialogue between Brenner and Gnessin? What is it good for? Whom, exactly, does it serve?”

Vizan’s answer is that it serves mostly Perry himself:

Perry’s new book, more than it is a story about “the homoerotic dialogue between Brenner and Gnessin, is the story of the fall of a giant who became, in his dotage, a hostage. His kidnapping finally confirms what has been known for a while: the changing of the guard in Hebrew academia, and the role flip between the former teachers (Perry) and their students (Gluzman), who now lead them, defeated and bludgeoned. . . mumbling others’ words with the heartwrenching, human, and understandable hope to remain relevant, to remain just a little bit loved, not necessarily homoerotically.

Arik Glassner’s critique, far less vicious than Vizan’s, more constructively addresses the heart of the problem. Glassner admires Perry’s pedantic and dogged documentation, though he gently admonishes him for his “excessive appetite for piquancy,” and he highlights the complexity around the appropriateness of Perry’s inquiry:

The question of “Brenner the fairy” is not mere gossip. Erotic distress is at the heart of the Brennerian creation, and therefore the question of the precise nature of the distress that preoccupied Brenner the person has deep meaning for the interpretation of his work as well. As opposed to Orin Morris’ critique in Ha’aretz, which sparked a heated debate on social media (including the brilliant argument that the conflicted relationship between Perry and Dan Miron as central to this book as the one between Brenner and Gnessin)—I think Perry represents a legitimate question here. Nevertheless, I do think that this position, the “Question of Brenner the Fairy,” which Perry sharpened and enhanced with the question of Gnessin’s reticence, does not quite hit the heart of the matter.

Glassner leaves open the question of the literary relevance of Brenner’s sexuality, and we will return to it. But first, we turn to another recent treatment of Brenner’s biography that eclipses even Perry’s.

Hilu’s Murder at the Red House: Sexuality, Mystery, Horror, and Thrill

If Perry’s book provoked sharp critique, Hilu’s Murder at the Red House, a fictional, speculative novel, caused uproar. Hilu, no stranger to mining the biographies of historical figures, is known for playing fast and loose with the boundaries between fact and fiction. His previous book, The Dajani Estate (2008) is a retelling of Shakespeare’s Hamlet, in which a Zionist agronomist, Haim Klorinsky (a real historical figure), starts an affair with a married Arab woman, Afifah, and takes over her estate after her husband suddenly dies. Afifa’s son, Salah, is convinced that Klorinsky murdered his father. The book made a splash,[1] and Hilu was praised for his virtuosic use of historical Hebrew and Arabic, but panned for his one-sided, villainizing perspective on Zionism. More importantly, Hilu was accused, by the Klorinsky estate, by author Aharon Meged and even by Attorney General Elyakim Rubinstein, of deliberately misrepresenting the legacy of a man who was known for his friendly and cooperative approach to the Arab population and his firm commitment to peaceful coexistence. Hilu eventually admitted that his purported reliance on real personal diaries was fabricated, and that the diary pages he had supposedly reproduced in the book were forged; after a mediation process between him and the Klorinsky estate, Hilu changed the protagonist’s name in subsequent editions, and added a lengthy disclaimer at the beginning of the book.

Either out of a sincere commitment to historical authenticity, or in a desire to avoid a second legal kerfuffle for maligning eminent cultural figures, Hilu equipped Murder at the Red House with two preemptive disclaimers. In a detailed afterword, he accurately and assiduously documented the known facts about the murder of Brenner and his companions. The trigger for the 1921 Pogrom was a violent clash between two May Day protests of rivaling Jewish political parties. The British police quelled the violence and pushed the communists to the Jewish neighborhood of Neve Shalom. The communists unleashed their furor against the police, the Jewish landlords, and their Arab neighbors, by continuing to provocatively wave red flags and sing the International in the vicinity of the Arab neighborhood of Manshiye. Fisticuffs broke, which escalated into a bloody armed conflict, in which hundreds on both sides were killed. The Hebrew authors’ murders occurred the next day and, save for the fame of the victims, would probably have been seen as one violence site among many. It is also known that, on the day before the murders, an Arab “lad” of an unknown age had disappeared, and his family had inquired after him at the Red House. Shortly before the murders, the neighboring Arab village held a funeral for a boy (it is unknown whether it was the same boy.) And it is unquestionably true that massive efforts were made to send a vehicle to Jaffa, to evacuate the house’s residents, and that they refused, sending some bee keepers who stayed with them, the Lerer family, in the vehicle in their stead. The Lerers attested that, the day before the murders, Luidor was sexually assaulted by a gang from Nablus and rescued by a Jewish man, and that he was deeply shaken by this experience. They also mentioned at the police inquest that there were hostilities between the residents of the Red House and an Arab gardner, Murad Alkarnawi, who cared for the nearby orchards.

In the introduction, he flags the holes in the evidence, which he sets out to speculate about in the novel:

What were the reasons that [Brenner and his author friends] gathered at the house on the day of the murder despite the turbulent political climate and despite the house’s dangerous location amidst Arab villages? What were the relationships between the residents? What was the reason for their incomprehensible (and ultimately fateful) choice not to get into the escape vehicle that arrived to pick them up the day before they were murdered? What were their connections with the Arab inhabitants of the nearby village, Abu Kabir? . . . Why were the bodies mutilated? What became of the body of Yosef Luidor? Was there a connection between the death of an Arab boy from the nearby village and the collective lynching?

There could be numerous ways to bridge these narrative gaps, but Hilu chooses to augment and center the possibility that the murder plot was closely related to sexual conduct and misconduct by Brenner and Luidor. As we saw in Perry’s book, this possibility, while explored in deeply unsettling directions, is far from being out of character for Brenner. Even Brenner biographers and documenters far less prurient than Perry all accept as plausible that he was attracted to men. Haim Be’er documents his mentoring relationships with young men and suggests that future biographers might explore these through a homosexual lens. Moreover, there is at least one confirmed story of a close, intimate, physical friendship (hugging and kissing), between Brenner and his landlords’ twelve-year-old daughter, Rachel Katinkaץ In interviews decades later, Katinka remembered the friendship fondly, expressed unreserved affection and warmth for Brenner, and mentioned that they remained in loving connection throughout her young adulthood, marriage, and motherhood, until his murder. Nevertheless, the relationship seems deeply unsavory, even predatory, through the lens of 21st century sensibilities, and even at the time, Brenner himself must have felt ambivalent about its morality, and about his own sexual proclivities; as early as 1907, he commented in Yiddish to Hillel Zeitlin that “the difference between pure and impure hands regarding [sexual behavior] is unclear to me”, and he left the Katinka home in haste in 1909.

Playing up the sexual possibilities to the max, Hilu’s Rashomon-style tale is narrated from three perspectives, starting with Luidor’s. Rescued by Brenner—the “Great Author”—from isolation and abject poverty, and invited to reside at the Red House, Luidor is initially grateful to Brenner and flattered by his attentions, until he learns that of Benner’s sexual interest in him. After initially rejecting Brenner’s unwanted advances, he succumbs, finding the experience traumatic and repellant. A lovesick Brenner promises to stop pestering Luidor if the latter refrains from having sex with another men. But unbeknownst to Brenner and others, Luidor meets and falls in love with an Arab “lad”, Abd’ul Wahab, and the two enjoy a beautiful, idealized romantic relationship in various hideouts around the neighboring Arab village, Abu Kabir. When Abd’ul Wahab disappears, Luidor frantically searches for him, coming upon what he believes to be a murder scene, and is immediately and brutally ambushed and sexually assaulted by a gang of Nablus men. Before he can compose himself, a group of beekeepers arrive at the house, alarming the inhabitants by telling them about a wave of pogroms against Jews in Jaffa and seeking shelter. The residents decide to leave the house immediately, and a rescue vehicle, procured with great effort, arrives to evacuate them. But Luidor has received a note from Abd’ul Wahab’s young sister, informing him that his lover is seriously ill and wishes to see him, and refuses to board the vehicle. Halfway to Tel Aviv, Brenner exits the vehicle and returns to the house, the others on his heels, and reunites with Luidor, explaining: “if I am unwilling to risk my life for my love, I do not deserve to be called a human, let alone a Hebrew author.” At night, news of Abd’ul Wahab’s death reach the house. It is too late to evacuate, but they decide to take shifts defending the house from a possible mob with the only rifle they have. A local cop, Ali Arafath, whom they consider an ally, offers to help, and they reveal to him their plan to flee through the back door during Abd’ul Wahab’s funeral.

The second narrator is Murad Alkarnawi, an old gardener, reminiscing about the events forty years later. His special connection to the orchard trees is disrupted when the Red House’s owner, Mantura, leases the house to the Jewish ranchers, who frighten and repel him. He is especially unsettled by the Jewish authors—especially “the bearded one,” Brenner, and “the limping one,” Luidor—whom he catches lovemaking in the orchard and alarming the trees. After he complains about them to the rancher, the two steal a valuable ax from Murad’s shed, falsely accusing him of stealing it (the ax is a gift from German gardeners) and getting him in trouble with Officer Arafath.

Murad is horrified to see “the limping one” grooming a young, dimwitted child (implied to be Abd’ul Wahab) and sexually assaulting him. The next day, the boy disappears, and his family frantically searches for him. The villagers are further alarmed by the May First labor parades and protests, in the ensuing violence, the dimwitted boy suddenly reappears, and is fatally shot in his stomach by a Jew. Murad, shoked and horrified, reports all he witnessed to Officer Arafath.

During the boy’s funeral, the villagers carry improvised weapons, to defend themselves against Jewish attacks. Ali Arafath urges restraint, but the villagers are shocked to see “the limping man” peeping through the Red House’s second story window, threatening them with a rifle even as the funeral processes. The stress upsets the donkey pulling the funeral cart, and when the boy’s corpse falls off the cart, “the limping man” deliberately shoots the innocent cart driver. The angry crowd storms the house, finding it empty, and then find the Jewish men—six of them, all armed—outside the house. The men shoot and kill many of the villagers.

The third story, implied to be the true version, is narrated by Raneen, Abd’ul Wahab’s sister and the only fictional character in the book, in 1971 (on the fiftieth anniversary of the murder). In her recollection, Abd’ul Wahab is neither a child or dimwitted—he is a gentle, effeminate teenager. Raneen befriends the Jewish residents of the Red House, enchanted by the empowered women and the kind farmers, but mostly by a goodhearted man (Brenner), whom she calls “the bear.” Learning to sneak into the Red House, unobserved, Raneen notices that Bear is deeply in love with a man with manicured nails (Luidor), and then, with alarm, that Nails falls for her own brother—a love that becomes mutual. Ali Arafath finds out from Murad—known by the children to be frightening and mentally ill—about the affair, and shares his suspicions with Abd’ul Wahab and Raneen’s parents. After an ensuing conflict, Abd’ul Wahab leaves the home, asking Raneen to bring food for him to a hut where he intends to stay. When she delivers the food, she overhears Officer Arafath blackmailing her brother: if Abd`ul Wahab does not persuade the Jews to sell a cow and give Arafath five hundred francs, Arafath will reveal the illicit relationship to Abd`ul Wahab’s father. As the whole village searches for Abd’ul Wahab, Raneen arrives in the shed, finding her brother dying from a self-inflicted gunshot to the stomach. His last words are, “five hundred francs.”

News of the death spread throughout the village. Amidst the collective horror and outcry, Ali Arafath orders Raneen to deliver a note to Nails (which we know is forged to appear from Raneen’s mother and claims Abd’ul Wahab is still alive). In this way, Arafath guarantees that Nails, and possibly the others, will choose not to evacuate, thus being present at the house when he orchestrates the raid during the funeral. Raneen, who does not know about the ploy, cooperates, and things unfold as Arafath had hoped: the officer exploits the funeral to incite the mourners against the Jews, falsely claiming that Abd’ul Wahab was murdered by a Jewish officer, and pretending to help the Jews escape while directing the villagers to the back door. Arafath then orchestrates the Jews’ brutal massacre and torture, including the burning of Luidor’s corpse. At the criminal murder trial, Abd’ul Wahab’s father and Arafath are acquitted; the father flees the country, and Arafath is ambushed and murdered by the Haganah.

Horrified and repelled by male violence, Raneen refuses to marry. Her eyesight, marred by the horrors she witnessed, deteriorates to almost complete blindness. Fifty years after the murder, she hears of a memorial for the murdered authors and attends it. She meets a Jewish woman of her own age, Rina, who is Yitzkar’s granddaughter. Raneen recalls meeting Rina at the Red House in their infancy, shares the full story of the murders wih her and, finally, finds peace.

As the recipient of the Sapir prize for his previous novel, Hilu provoked a splash with Murder at the Red House, which was especially praised by queer critics. Filmmaker Gal Ohovsky’s laudatory review read:

Despite the fact that it centers a love story between two men, this book cannot be described as a homosexual affair. As in [his previous books], Hilu uses homosexuality as a background for uncovering the subterranean currents between different cultures, opposing worldviews, and the documentation of human diversity. This is not a simple, beautiful, rewarding homosexual novel like “call me by your name.” What we do have here is a love-hate relationship between Luidor and Brenner who constantly desires him, and there is the complicated relationship between the Jewish intellectual and the Arab boy who, according to one of the versions, is a bit dimwitted. Homosexuality serves here as a way to examine prejudices and social taboos. With great delicacy, Hilu manages to tell a painful historical tale, and also to describe interpersonal sensitivity in an insensitive place. Whoever looks for an amiable telenovela featuring two men, in love and kissing, might be disappointed.

Other reviews were far less sanguine. An editorial in Yisrael Hayom praised Hilu’s style of writing and his gift for intriguing the readers, but raised serious qualms about the ethics of Hilu’s creation:

Is it appropriate to do so? Can a man produce a book that relates the fictional, or half-fictional, biographies of flesh-and-blood people and write in it whatever he fancies, tie to their characters any qualities, choices, deeds, and words that he wishes? Or should such freedom be limited to whoever writes on well-known people, who cannot hide in the shadow of their anonymity and their very celebrity kosherizes writing about them?

An even more negative perspective was articulated by critic Maya Sela for Ha’aretz:

The novel’s motto is “The early ones are not remembered” (Ecclesiastes 1: 11), as if the book intends to serve as a memorial. When I read it, a different biblical passage echoed in my ears as an alternative motto: “What have you done? Hark, your brother’s blood cries out to Me from the ground” (Genesis 4: 10). It was hard not to think of Hilu’s actions here as a sexual assault on history—a rather homophobic sexual assault, including completely stripping his characters of any humanity, thought or idea in favor of them being homosexuals and nothing else.

But Sela’s main concern with Hilu’s work is with literature. She pans the way he crassly crafts the facts, admitting that many of the horrifying, gratuitously lurid details he revels in describing did not, by his own admission in the epilogue, actually happen. She then expresses grave concerns about the value of the literary exercise:

The things the author wrote in the introduction and epilogue raise some substantial questions about literature and its role as intellectual amusement without any obligations—not to shaping, not to language, not to style, not to history, not to ethics, not to good taste, and not to the ancient, forgotten art of the storyteller. In that, the novel also exemplifies what can go wrong when authors do not write literature, but rather engage in sociology, gender, psychology, politics, and law. Maybe because this book was borne out of intellectual amusement, there is not a single moment where the reader can be sucked into the loose tale and find in it any logic, grace, or taste.

Hilu tried to examine things that remained mysterious to him, but the truth is that there isn’t much of a mystery here. The six Jews were murdered because they were Jews who settled at a place where there were already people, as has happened since then to this day—Jews and Arabs fighting and killing each other in a war over the land.

I fancied that I heard Brenner’s blood crying out to us from the Earth and begging that we stop sexually assaulting him, but it’s possible that he was crying the cry of literature. Perhaps he does not care about historical truth, perhaps he already understands postmodernism, he certainly understands melancholy and emptiness, but what will be of literature, he wonders, perhaps, still demanding the right to cry out.

Is Brenner’s Work Queer Work, the Work of a Queer Author, Both, or Neither?

Perry and Hilu critics seem to object to the use of Brenner’s sexuality as crass exploitation, wondering whether the two works are crafted to pander to the readers’ basest instincts, and wondering about the value of the exercise given what we already know, without such graphic elaboration on Brenner’s corporeality, about his conflicted sexuality. According to this critique, the blow-by-blow elaborations, fictional, speculative, or otherwise, contribute nothing to our lives beyond the satisfaction of prurient interests. But Arik Glassner, whose critique of Perry’s book I presented above, is willing to consider the questions of Brenner’s biography relevant to our understanding of his work. Elsewhere in his review he writes that the notion that the rift between Brenner and Gnessin stemmed from the latter’s “gay panic” and avoidance is “not preposterous, but it’s worth saying a few things about it”:

First, it’s worth distinguishing between the question whether Brenner was attracted to Gnessin and the question whether Brenner was attracted to men at all. Regarding Gnessin specifically—perhaps. Regarding men in general, I’m doubtful. Shofman, a friend of Brenner’s and not at all a naïve man, wrote about Brenner that “his painful point” was the thought that women do not fancy him. In a critical essay about Poznansky, Brenner himself observes that Poznansky differs from others, and apparently from Brenner himself, “in that the erotic is not a touch of leprosy in the life [of Poznansky’s novel protagonists], but rather a welcome source of emotional glow, of magical ruminations, of lyrical sesntiments. ‘The worm of envy’ does not eat at the heart [of his protagonists]. Au contraire, may the senior student realists fraternize with the junior female students of the gymnasium—and all the power to them!” The implication is that the erotic is “a touch of leprosy” for those who envy others’ sexual successes.

I tend to think that the inner erotic world of Brenner’s protagonists is much closer to that of the protagonists of Ya’acov Shabtai and Hanokh Levine. In fact, Brenner, to me, is the one who made these protagonists possible in our culture. These are straight heroes who are haunted by sexual inferiority sentiments and envy of exploding virility, and the heartrendering esthetic treatment by the male triangle Brenner-Levine-Shabtai of these painful topics has made this theme central to Hebrew literature.

Glassner’s point is well taken, but I submit that he does not take it far enough. While definitions of queer theory vary considerably, some suggest a broad understanding of the “queer gaze” (Burnston & Richardson 1995). According to these broader perspectives, one’s experience of being an outsider-looking-in, perennially feeling out of place in visible and invisible ways, code-switching, and sometimes furtively hiding in plain sight, in a heteronormative society where openness could sometimes result in serious life-threatening consequences, has the power of opening one’s eyes to many other displays of inequality, injustice, and exclusive assumptions—beyond those directly related to sexual identity or expression. The loneliness that can result from a closeted life could generate deep empathy for lonely people everywhere. Understanding how experiencing one’s own unconventional sexual attractions in a society where these things are unspoken (and would remain unspoken until the 1960s) can illuminate more general, and possibly coded, references to deep helplessness, a sense of “being stuck,” and experiences of shattered, fragmented identity.

An instructive way to consider whether this perspective can add to our understanding and enjoyment of Brenner’s work is to see how he was read by critics and scholars of prior decades, for whom the personal/sexual biography aspect was inaccessible either because they had no idea of it or because it was taboo. In his 1977 book Brenner’s Art of Story, Yaacov Even, whose analysis never veers anywhere near Brenner’s interiority (sexual or otherwise), sees the central theme of Brenner’s work as the struggle of a complicated hero—usually a former yeshiva student turned secular, almost devoid of friendship and intimacy, and unmoored from his cultural context even as he strips off the suffocating confinement of the religious world—to survive in an ugly, unjust, alienated world that in need of urgent moral and spiritual repair. This general truth manifests in different ways in Brenner’s novels. In Winter (1904) the hero, departing the shtetl for a big Russian city and joining a circle of intellectuals, discovers that his new milieu is nothing more than a modern manifestation of the ghetto he left behind. In From Here and There (1911), the hero is similarly disillusioned with the New York City underworld (set in the Lower East Side and resembling Brenner’s Whitechapel’s experience). Several of Brenner’s novels—notably, Beyond the Border (1907)—paint the world’s oppressiveness and cruelty at its most extreme through descriptions of compulsory military service and various carceral settings for military defectors. And lest these appear to suggest that the answer to these conflicts is Eretz Israel, Brenner’s greatest work, Bereavement and Failure (1914), reveals the same oppression, indifference, and cruelty among Zionist immigrants of the first Aliyah.

Bereavement and Failure is especially remarkable because, for many halutzim, who yearned to shed stifling religious environments and home lives, Zionist immigration held the promise of freedom: newfound connection to the land, new ways to literally embody their ideals through agricultural work, and an empowering rejection of the stereotypical exilic, effeminate weakling. Brenner was an enthusiastic believer in the Zionist dream and devoted his life to the revival of the Hebrew Language, and he was deeply committed to the success of the exercise, to the point that he was willing to walk away from his meteoric literary career and become a farm laborer. That someone in Brenner’s position, having been expelled from his only viable career path at the yeshiva, spent a coerced and frightening stint in the army, and lived in various European cities in abject poverty, would fully buy into the Zionist dream and yet, upon attaining that dream, bravely and perceptively indict his new environment for being as stifling and constrictive as all the other environments he previously occupied, is nothing short of genius, integrity, and true courage, and could be the product of two factors or both. First, as a deeply closeted man who experienced deep, unrequited love that truly could not say its name, with a traumatic ending, whose devastating psychological effects he could hardly keep from wearing on his sleeve but could openly discuss with no one, Brenner would carry his anguish and emotional suffocation with him wherever he went, for the rest of his life. It would be so central to his human experience that a geographic change, even dramatic and supported by exuberant ideological hope, would not enable him to shed it. Second, Brenner could be one of those rare people blessed with boundless sensitivity for the universal human condition, whose ability to identify invisible threads of human distress and suffering could transcend his personal experience. Given the artistry with which Brenner shaped his unhappy, stuck heroes, with both ridicule and empathy, I find both possibilities plausible, and perhaps more valuable than those offered by Perry, Hilu, and their critics.

Personalizing Grief, Queering Mourning

Another possible explanation for the recency of interest in Brenner’s sexuality could be the changing landscape of grief, mourning, and bereavement in Israel. Some of these shifts echo universal trends: the exhortation to avoid speaking ill of the dead has been deeply undermined by the gradual empowerment of victims of sexual assault and bullying to speak up, years before the #metoo movement but more extensively in its wake. Exposés of sexual misconduct—unethical or criminal—have provoked countless cultural debates about the need to reassess the public image and cultural contributions of people whose reputations are tarnished by accusations and, sometimes, by proven facts. At the same time, changing mores regarding the acceptability of unconventional identities have allowed fuller appreciation and mourning of people whose suffering in life and in death from a stigmatized disease was silenced or minimized, such as Rock Hudson and Ofra Haza.

There are, however, aspects to the changing forms of bereavement that are uniquely Israeli. For a reader in 2024, the murders at the Red House strongly and keenly reverberate the October 7 massacre, provoking a well of horror and grief. But for people who read Brenner’s books in the 1950s and 1960s, the horrors of pre-World-War-II pogroms and killings paled in comparison to the all-encompassing horrors of the Holocaust. Shocked locals, meeting Holocaust survivors for the first time in the late 1940s and unable to make sense of the horror, reacted with guilt, shame, and mistrust: “How come you survived and so many died?” “Why did you go like sheep to the slaughter and did not try to fight?” In the early years of Israel’s existence, therefore, the collective memory of the Holocaust was characterized by the schism between the Holocaust martyrs and heroes, emphasizing the bravery and revolt of the few while neglecting the physical suffering of the victims. Gradually, as Holocaust survivors found their voices and their testimonies were deemed valuable, Holocaust memory became collectivized, to the point that it is now widely experienced and felt as a national trauma, regardless of family connection to the Holocaust, ossified through the rituals of Holocaust Day, and marshalled to convey the message of commitment to ensure the future of the Jewish people, closely entwined with the project of realizing Jewish life in the State of Israel.

Similarly, the collective commemoration of military deaths in Israel was initially crafted in two ways that Liat Granek (2014) refers to as “mourning sicknesses”: the urge for parents to display bravery and resign and refrain from showing emotion, and the political manipulation of grief as justification for war, aggression, and violence. As with Holocaust remembrance, the emphasis on bravery and the worth of sacrifice normalized the distinctions made between whose lives were deemed grievable and whose lives are considered worthless and unmournable.

Since the 1980s, this hegemonic pattern of mourning has been gradually eroded and undermined. The eroding political consensus led to the eschewing of collective, official narratives of death, in favor of an expansion of individualized, personal remembrances. Udi Lebel (2011) exemplifies this process through an analysis of the bereavement models of parents of fallen soldiers. Before the Yom Kippur war, the activities of bereaved parents were channeled by the state to public sites and commemoration practices, and bereavement was, in effect, nationalized. However, in the aftermath of the Yom Kippur War fiasco, complete with widespread political protest and the Agranat Inquiry Board, and following the Lebanese incursion of 1982, a political bereavement model became dominant. Parents blamed the government for the death of their children and engaged in media and political protest activities. This trend intensified in the 1990s when, against the backdrop of human rights legislation and the prospect of a peace agreement with the Palestinians, bereaved parents whose sons had been killed in training accidents and military failures adopted a model of civilian criticism of the army. This alienation from hegemonic rituals, which increasingly clashed with the standard commemorative practices, was especially striking for families whose political views did not align with government policies, and for families whose sociocultural and economic circumstances disconnected them from the national ethos, such as new immigrants from Russia and Ethiopia.

The model of individualizing death and mourning, as well as mourners’ protest against governmental ineptitude or violence, continues to characterize bereavement in Israel. Among the most outspoken critics of the 2024 war in Gaza are family members of soldiers and civilians slaughtered in the October 7 massacre, who see Netanyahu as the chief culprit in the country’s unpreparedness for the massacre and the war as a self-centered distraction from the desperate need to redeem the hostages through diplomatic means. The families of the hostages use social media to publish their loved ones’ images, telling stories about them and their lives, and introducing the Israeli public to their family members, pets, hobbies, and contributions to their local communities.

This individualized model of bereavement has bled over to less recent losses. Holocaust education in Israel is now far more individualized than it was decades ago. Israeli textbooks no longer deal in abstract numbers (“the six million”), opting instead to tell individual stories about children in the Holocaust. Military mourning has also changed, not just for recently bereaved parents, but also to those who lost loved ones in wars decades ago.

More than a century has passed since Brenner’s murder. Perhaps the surge of interest in his personal life suggests that the horror of his murder, silenced by the media in the 1920s and unspoken for years, subsumed into the horrors of the holocaust, is finally ready for processing, through the current bereavement model: a celebration of Brenner as a private person, rather than merely as a national hero, and an openhearted look into the lights and shadows of his psyche.

***

It’s important to keep thingsi n perspective, though. Despite the open secret of Brenner’s complicated sexuality—many of the facts about his personal life are either known or surmised—it has taken more than a century for two books to center these issues and marinade in them, and even that encountered fierce resistance. The fact that this issue still generates considerable heat in literary circles shows that, despite the rise in identitarian approaches to literary criticism and in wresting control of tragedy away from hegemonic patterns—or maybe because of them—some aspects of Brenner’s life are still controversial, though perhaps not to the extent they were in his lifetime.

Whether one sees merit in the exercise of revisiting the personal and embodied lives of cultural giants, every human being is more than a sum of their group identities. Brenner might have wrestled with silenced and unrequited desires, and he was far from a perfect, “put together” person. At the same time, he was blessed with a rare, sparkling intellect, and with a heart open to identifying and protesting injustice and cruelty. Those unique gifts are what made him a literary luminary, and will hopefully continue to be guide our path when we lionize literary heroes, in all their remarkable flaws and beautiful imperfections.