Something is rotten in the state of California. Rotten throughout, from top to bottom. In today’s post I juxtapose for you four pieces from the last couple of days, which illuminate just how much trouble we’re in.

Scene 1: The SATF Horror and the Geography of Prison Remoteness

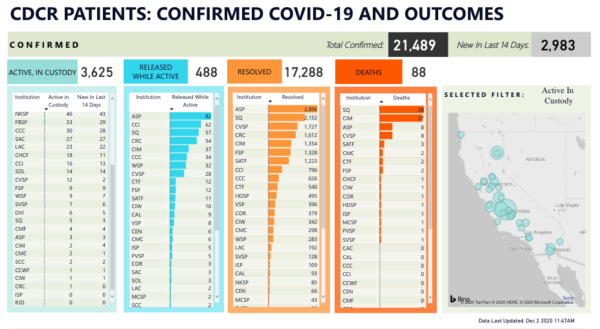

Throughout the summer, the public gaze was laser focused on San Quentin. There was a good reason for this; at 2,239 cases and 29 deaths, the outbreak at Quentin was the worst COVID-19 outbreak in the nation and the worst medical prison disaster in the country’s history. But as has been the case throughout this ordeal, once attention turns somewhere, the government’s or anyone else’s, the virus has already found opportunities elsewhere. By the time the litigation surrounding the Quentin catastrophe matured into an order and started moving toward fashioning remedies, the pestilence metastasized elsewhere–whether through a careless employee or a botched transfer, we won’t know. The CDCR population infection count shows numerous large outbreaks, to the tunes of hundreds of people, in prisons located in rural areas. Jason Fagone’s recent Chron story turns the focus to the Substance Abuse Treatment Facility (SATF) in Kings County, the largest prison in the state, which is operating at 128% of capacity. Not only is the outbreak there horrible, and has already claimed lives, but the conduct of prison authorities there seems absolutely appalling:

In just the past two weeks, 713 men in custody at SATF [now 851 – H.A.] have tested positive for the coronavirus, according to CDCR’s web tracker, and as of last week, 150 staff members were infected. Half of the facility’s 4,400 prisoners have caught the virus since August. Three have died.

One day last week, when prison staff tried to move a new man into an empty spot in Meyer’s eight-man cell, he got nervous, he said in an interview via JPay, a prison email service. Days earlier, another man sleeping mere feet away from Meyer had developed COVID-19 symptoms and was removed by staff, and Meyer suspected that his new cellmate might also be infectious. Meyer approached the officers’ station and complained, saying he didn’t want to be housed with a potentially contagious person. That’s when he was handcuffed, Meyer said.

Two days ago I talked with Sam Lewis of the Anti-Recidivism Coalition about the possibility of a vaccine for incarcerated populations, and one of the points he brought up was the proximity of San Quentin to white, wealthy Marin County. I think Sam was right to say that Quentin receives an inordinate amount of attention, but I suspect race and class play into this situation in ways that have more to do with political culture, proximity, and opportunity. Quentin is extremely close to the Bay Area, where all kinds of do-gooders like me have easy daily access to the prison; if there’s no traffic, it takes approximately 35 minutes to drive to Quentin from my house. Given that, for decades, prison programming has been slashed–most recently, this was one of the negative effects of the recession–the availability of a cadre of academics and activists as volunteers produces a rich array of programming (go ahead, click on each link, and I could offer more.) Because parole hearings emphasize programming and encourage people to talk in “programspeak”, and because of the paucity of programming elsewhere in the system, people are desperate to come to Quentin and avail themselves of these opportunities as much as they can if they ever want to be approved for parole.

By contrast, California’s other large prisons are located in rural areas, mostly in poor towns that were persuaded to accept prison siting and become a “company town” because of the promise of jobs. These places are not squeaky wheels, and for Bay Area or Los Angeles do-gooders they are difficult to access. For example, during the Pelican Bay hunger strike, my students had to drive 8-9 hours to visit the strikers, which implies huge barriers for visitors without the means to drive or stay at a hotel. These places are not “squeaky wheels”, and it’s quite difficult to get the programming “grease” there. Also, it means that the voices raising serious concerns about the outrages that happen in these rural prisons are far less amplified by voices of high-profile, concerned progressive politicians.

Scene 2: Inaction Figures

The Chronicle is on a roll, continuing with a hard-hitting, data-intensive piece by Nora Mishanec. Mishanec managed to obtain a demographic breakdown of the thousands of people who were released by CDCR since Newsom promised 8,000 releases by the end of the summer. It’s not summer anymore, of course, and even when the plan was proposed it was already underwhelming–too little, too late, too piecemeal, and too restrictive. I am sorry to say that this sad excuse for pandemic relief played out exactly as I had predicted, and please believe me that I take no pleasure in having been 100% right.

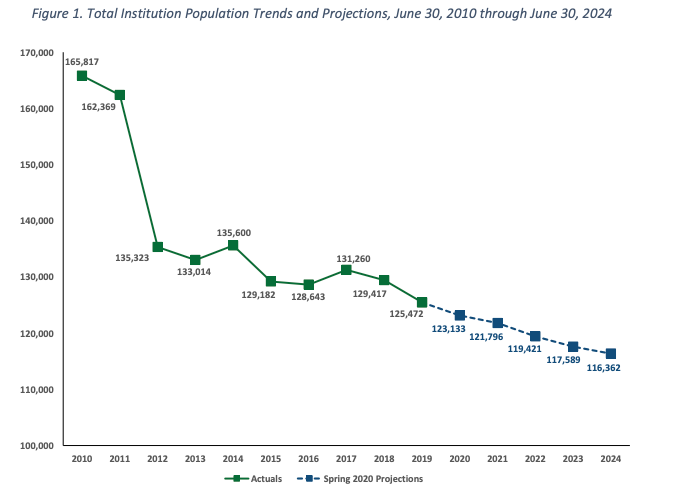

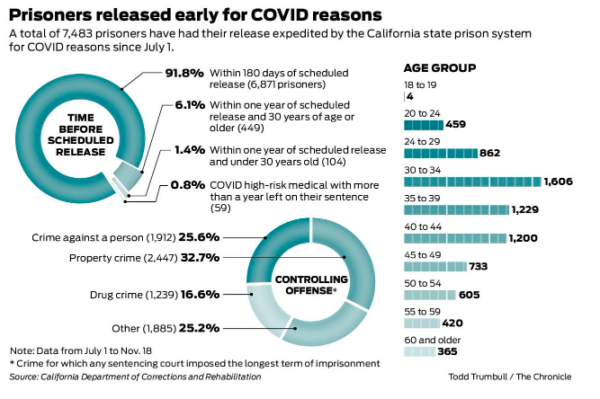

This graphic from the Chron story gives you an idea of who was released and who was not. Take a look at the circle in the top left. The vast majority of people who have been released had only months left on their sentence back in early July. It is now early December, and these folks would have gotten out by now anyway–they just got a wee push on the way out the door to hasten their release. This is something that happens all the time in California prisons, pandemic or no pandemic: every month thousands of people churn in and out of the system, the folks whose sentences have ended to be exchanged for folks coming in from jails (The population reduction here is artificial, and stems from the halt of transfers from jails–but the carceral apparatus as a whole is bursting at the seams, and of course now the jails are seeing their own COVID-19 horrors and are grossly over-capacity. Something’s gotta give, and there are already jail lawsuits.) Only 0.8% of the people who were released were deemed “COVID high-risk medical”, when a full quarter of the population on the eve of the pandemic was people aged 50 and over.

Why, you might wonder, are so few of the people who got released in the over-50 bracket (1,390 out of 7483)? The answer is in the bottom right. People convicted of violent crime who, unsurprisingly, serve longer sentences and, also unsurprisingly, are older because of it, are underrepresented. Those are also the folks at highest risk of contagion and serious complications. But this plan was not designed with public health in mind–it was designed to avoid headlines like “Newsom Releases Murderers, Yikes.” And so here we are.

Scene 3: Insult to Injury

If they’re not laboriously and efficiently going over people’s files and releasing grandparents back to their families, what, pray tell, are state officials busy doing? I’m so glad you asked: The best and brightest at the California Attorney General’s Office are busy not only petitioning the California Supreme Court to review the population reduction order in Von Staich and jamming the wheels on hundreds of habeas petitions, they are petitioning the court to depublish the decision itself. Yes, you heard it right. Dozens dead, tens of thousands infected, and the most pressing order of business is to obliterate from bureaucratic memory that there were compassionate, humane, knowledgeable judges, who recognized a human rights crime when they saw one, and acted accordingly.

You are incredulous? I get it. So was I. Here’s the whole thing for you to read.

VON STAICH Request for DePublication by hadaraviram on Scribd

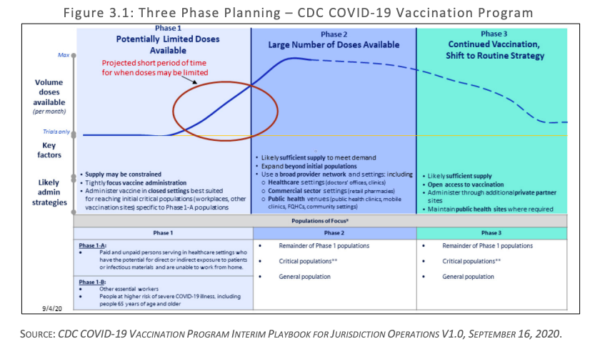

What more is there to say about this? At every junction, when the opportunity emerges to do the right thing, these folks are doing the exact opposite. We are going to pay dearly for this concerted cruelty when the time comes to get buy-in for vaccination (that is, if anyone there might ever see prisons for what they are, which is confined, crowded spaces, and actually prioritize “murderers, yikes.” Want to know why it is important to vaccinate? here’s my op-ed in the Chron about this.) By the time the vaccine comes to the prison gate, people will not believe CDCR that it is in their benefit to take it, and while I find this awful and deeply disappointing, I deeply understand where the suspicion and resentment come from.

Scene 4: No Bad Deed Goes Unrewarded

What is going to happen to all these folks, who have worked so hard for months to keep aging, infirm people languishing behind bars, vulnerable to the pandemic? Gosh, I’m so glad you asked, because California’s AG Xavier Becerra, whose signature decorates everything you’ve seen defending CDCR in courts since March, is being tapped for a position in the Biden cabinet.

Look, I’m not a member of the no-lesser-evil brigade, and in November I cheerfully and without reservations voted for Democrats, even Democrats who have deeply disappointed me, because the alternative was to keep a despotic, sociopathic, semiliterate career criminal in office. For four years I was a vortex of disdain for the repertoire of cruelties of the Trump Administration, and I’m thrilled the people I voted for won. Elections are a buffet at a roadside motel, not a personalized meal. But when you’re handling what we call a “Big Bad” in TV tropes, the other side automatically becomes “the good guys,” and critique of them is muted, or at least softened–even when the courageous leaders of La Résistance forget about the burden of proof or flip-flop about the death penalty. I suspect it won’t be long before we forget how Monsieur et Madame Blanchisserie Française, the delectable taste of Yountville gastronomy still fresh in their mouths, proceeded to close our children’s playgrounds with not a shred of medical evidence connecting them to outbreaks. I get it. We’re grownups, politicians are politicians even when they are generally on the right side, and people should not be expected to be perfect. But I’m frustrated that the nature of California politics creates the illusion that we are a blue, progressive state, in the face of everything that has been going on.

Why is it that we appear so blue when our prisons are such a horror show? My colleague Vanessa Barker offers a convincing explanation. By contrast to the East Coast, or even the Pacific Northwest, California’s political culture is both deeply polarized and populistic. Our red counties, which are, after all, where most of our prisons are, are deeply red; jails there are run by red sheriffs and prisons by red CDCR officers. A lot of decisionmaking happens on a local level. Even when a prison is located in a blue county, such as San Quentin in Marin, prison officials refuse to collaborate with county health officials, citing jurisdiction. Moreover, we tend to legislate our criminal justice arena via referendum, which creates a lot of the horrors that I recount in Chapter 2 of Yesterday’s Monsters: a salience of a particular class of victims as the moral interlocutors of criminal justice, inflammatory rhetoric, and a lot of money backing up fear and hate.

The consequence of this is that our elected officials, who are so right on so many things (immigration, healthcare, climate action) are so often so wrong about criminal justice. Some of what we have going on is so deeply ridiculous–to name just one example, moratorium on a death penalty that should have been abolished eons ago, and because of populist stubbornness we can’t reap the huge economic benefits of abolition–and it is difficult to explain to lefty friends on the opposite coast how come people who appear to be such heroes on the national stage act in such villainous ways on the local stage.

This week, I recommend that you keep your gaze on some of the newest outbreak sites. Beyond SATF, there are also serious outbreaks in PVSP (643 new cases), HVDP (473), MCSP (416), CTF (284), and VSP (298). Dozens of other facilities have “only” dozens of cases. The only CDCR facility with no cases at present is RJD. The death toll systemwide has risen to 90.