- Hola Amigos Latinoamericanos y Centroamericanos, y otros amigos que hablan español. Hoy di una plática, via Zoom, a la Facultad de Derecho en la Universidad de Buenos Aires sobre las políticas penales durante la administración Trump. Se me ocurrió que quizás hay mas gente que habla español y se interesa en el tema, y por eso aquí están mis notas para la plática. En unos dias, publicaremos la plática entera en YouTube y la ubicaré aquí.

- Antes de discutir la política de justicia penal de la administración Trump, es importante preparar el escenario con algunas características únicas del panorama penológico estadounidense.

- Los EE. UU. son los campeones internacionales del encarcelamiento, pero no es un campeonato que nos da orgullo: tenemos cuatro porciento de la población mundial pero veintidós porciento de la población mundial de prisionerors! Los Estados Unidos tienen setecientos treinta y siete prisioneros por cien mil de populación. En dos mil diecisiete Argentina tuvo doscientos siete.

- En dos mil siete, uno en cien personas en los EE. UU. estaba encarcelado.

- Este encarcelamiento masivo trasciende los muros de la prisión: uno en 33 estaba bajo alguna forma de supervisión estatal, por ejemplo libertad condicional después de servir una sentencia en la cárcel.

- Además, los riesgos de encarcelamiento no se distribuyen de manera uniforme entre la población y varían drásticamente según la raza, la clase y el género. Para hombres jóvenes Africanos-Americanos – uno en 3 estaba encarcelado (!!!)

- Pero Estados Unidos es un país muy grande y existe una gran variación en el encarcelamiento dentro de él. Para comprender esto, es importante tener en cuenta que no solo tenemos un sistema de justicia penal: tenemos un sistema federal, cincuenta sistemas estatales independientes y numerosos tribunales indígenas independientes.

- Para complicar aún más las cosas, incluso el sistema estatal es una generalización excesiva. Hay dos estructuras administrativas superpuestas: el nivel municipal y el nivel de condado.

- La policía es municipal – cada ciudad, incluso los pueblos mas pequeños, tiene su propia forza policial. Tenemos dieciocho mil diferentes departamentos de policía.

- En cambio, nuestros tribunales y fiscalias operan en el nivel del condado.

- Tenemos prisiones estadales y carceles mas pequenas, que llamamos “jails”, en el nivel del condado. Esto es importante porque los costos del encarcelamiento corren a cargo de diferentes niveles administrativos. En otras palabras, las fiscalías y las cortes no tienen un incentivo financiero para reducir el encarcelamiento, porque los condados no pagan por el encarcelamiento. Mi colega Frank Zimring llama esto “el almuerzo gratis correccional.”

- Otra consecuencia de la fragmentación de Estados Unidos es que los niveles penales y los “sabores” penales se ven muy diferentes en todo el país.

- Por ejemplo, en California, donde yo vivo, las políticas penales son una combinación de leyes y de referendos publicos, resultando en un populismo penal que es especialmente sensible a las apelaciones punitivas en nombre de las víctimas de delitos. El resultado es una maquina gigantesca de encarcelamiento, incluyendo el corredor de muerte mas grandee en los EE. UU, y muchas sentencias muy largas. Un tercio de los presos en california está cumpliendo cadena perpetua, ya sea sin posibilidad de liberación o con una posibilidad muy lejana de liberación. Mi libro nuevo Yesterday’s Monsters es sobre esta populación.

- El noreste es gobernado de una manera menos populista y mas elitista, y por eso las sentencias son menos punitivas.

- El noroeste es aun menos punitivo. Muchas de las reformas que mejoraron la guerra contra las drogas comenzaron en el noroeste del Pacífico.

- El sud tiene un legado trágico de racismo y esclavitud. Muchos de los problemas politicos que todavia son reflejados en las politicas penales en el sud originan desde antes de la Guerra Civil. Durante los años sesenta, la Corte Suprema introdujo algunos estándares de derechos civiles y debido proceso que corrigieron algunos de los peores aspectos de la justicia penal del Sur. Pero todavía las condiciones en muchas prisiones en el sur imitan las plantaciones anterior de la guerra.

- La justicia penal en el suroeste se caracteriza por la hostilidad hacia los inmigrantes de Centroamérica. Muchos de los casos de drogas en el suroeste involucran pequeñas cantidades de marihuana contrabandeadas a través de la frontera. La política fronteriza también conduce a cierta corrupción policial que implica la confiscación de dinero y objetos.

- A pesar de estas diferencias locales, existen algunas características comunes al panorama de la justicia penal estadounidense, y es posible que le recuerden bastante la situación en varios países de América Central y del Sur.

- Ya hablé un poco del legado nacional de colonialismo y racism, pero es importante decir que no se limita al sur del pais. ésto se manifiesta de dos formas. Primero, la policía estadounidense tiende a operar de manera racializada, lo que significa más arrestos y hostigamientos en vecindarios donde viven minorías raciales. En segundo lugar, debido a un legado de privaciones y falta de oportunidades, las minorías raciales están sobrerrepresentadas en los delitos violentos, tanto como perpetradores como víctimas.

- Otra caracteristica es la proliferación de armas legales e ilegales. En Argentina es necesario tener CLUSE para armas, y uno tiene que presentar una solicitud y aprobar exámenes de competencia de salud física y mental. En cambio, en las EE. UU. Es muy fácil comprar armas. Para muchas personas, el derecho constitucional a portar armas alcanza proporciones míticas, algo relacionadas con el legado de la justicia fronteriza.

- Los EE. UU. Tienen una cultura policial de violencia, entrelazada con politicas de arrestos y registros por motivos raciales. Hay un problema especial con abuso de fuerza, especialmente con matanzas.

- Además, hay un legado difícil de corrupción política (incluso a nivel estatal, local y del condado.)

- La trayectoria de encarcelamiento Estadounidiense continuó aumentando hasta la crisis financiera de 2008, que transformó la justicia penal estadounidense de manera importante. Este fue el tema de mi primer libro, Cheap on Crime.

- El desarrollo más importante fue la prominencia de un discurso fiscal, centrado en los ahorros de la justicia penal. Durante décadas hubo un callejón sin salida entre el apoyo conservador a la seguridad pública y el apoyo progresivo a la descarceración. El hecho de que la crisis hiciera que el encarcelamiento masivo fuera económicamente insostenible ayudó a salvar estas diferencias con ideas sobre la parsimonia que todos pudieran considerar. Estos cambios estaban en sintonía con las lógicas neoliberales, y voy a explicar de cual manera.

- La dependencia del discurso del ahorro también permitió la formación de coaliciones bipartidistas entre progresistas que intentaban reducir la maquinaria carcelaria y los libertarios de los gobiernos pequeños que estaban hartos de los gastos de la guerra contra las drogas y el encarcelamiento.

- Estas coaliciones resultaron en una variedad de practicas de ahorro: muchas cárceles fueron cerradas o fusionadas con otras instituciones, muchas políticas consistieron en mas bajas sentencias, especialmente para delitos de drogas, y diez estados abolieron o suspendieron la pena de muerte. La economía de las prisiones privadas también cambiaron: Con la reducción del mercado del encarcelamiento nacional, los empresarios de prisiones comenzaron a invertir en el creciente mercado de la detención de inmigrantes.

- Las lógicas neoliberales se manifestaron también en cambios en la percepción de los presos: en lugar de verlos como responsabilidad del estado, ellos fueron percibidos como “clientes” involuntarios del estado. Las nuevas politicas prestaron atención a categorías de presos previamente invisibles: los ancianos y los enfermos. Además, muchos costos de encarcelamiento se transfirieron a los propios reclusos, lo que en algunos casos resultó en que las personas debían pagar por su propio encarcelamiento.

- No todas las reformas fueron puramente economicas. La indignación pública por la violencia policial, especialmente contra las minorías raciales, produjo algunas reformas de la era de Obama, como la eliminación de las sentencias mínimas obligatorias para los infractores no violentos de drogas.

- Estas politicas federales ocurrieron junto con muchas políticas estatales que legalizaron el uso y posesión de marihuana al nivel del estado.

- El ascenso de Donald Trump, notablemente, dejó algunas de estas reformas en su lugar, al tiempo que cambió drásticamente el ánimo detrás de otras.

- Tengan en cuenta, como dije antes, que la mayoría de las políticas de justicia penal en los Estados Unidos se hacen a nivel local, donde la administración federal tiene un impacto muy limitado. No obstante, hubo rupturas significativas durante el mandato del primer fiscal general de Trump, Jeff Sessions, y el segundo, William Barr. Hablaremos de seis:

- Falsa Conexión entre Inmigración y Criminalidad

- Animando la Lucha contra las Drogas

- Animando la Pena de Muerte

- Interviniendo en la Justicia Local

- Obstrucción de la Justicia contra los Poderosos

- Y quizá la mas significantive, Cambios en la Corte Suprema

- Falsa Conexión entre Inmigración y Criminalidad

- Desde los primeros días de su campaña presidencial, Trump confió en reunir a sus partidarios a través de promesas xenófobas para frenar la inmigración. Una gran parte de la campaña se dedicó a promocionar una correlación entre inmigración y criminalidad.

- Esta conexión es cien por ciento falsa. Existe un sólido cuerpo de investigación empírica, que cubre diversos tiempos y lugares, y todas las investigaciones llegan a la misma conclusión: los inmigrantes cometen menos delitos, en todas las categorías de delitos, que los nativos.

- La falsa suposición de que los inmigrantes son un peligro para la seguridad pública se basa en inseguridades económicas profundamente arraigadas, principalmente de los hombres blancos, de que los inmigrantes aceptarán trabajos estadounidenses.

- Una gran parte de la política de justicia penal estadounidense, como la criminalización de ciertas drogas, se creó para criminalizar los comportamientos de los inmigrantes a fin de mitigar estos temores.

- Además de las políticas xenófobas bien publicitadas, incluida la prohibición de los viajeros de países musulmanes y las separaciones familiares, la administración Trump prosiguió los procedimientos de deportación sobre la base de condenas penales, por lo que la aplicación de la ley de inmigración es la principal preocupación del departamento de justicia.

- Animando la Lucha contra las Drogas

- Cuando fue elegido para el cargo, Jeff Sessions anunció públicamente que los consumidores de marihuana eran “malas personas”, una afirmación fuera de contacto con las sensibilidades bipartisanas de republicanos y demócratas, que apoyaron una tregua en la lucha contra las Drogas

- La administración procedió a revertir las restricciones de la era de Obama y perseguir casos federales contra infractores de drogas en estados en los que el uso y posesión de drogas son legales.

- Pero al mismo tiempo, estados y ciudades continuaron sus politicas regulatorias. Marijuana se legalizo en mas estados, y algunos estados y ciudades decriminalizaron otras drogas tambien.

- Animando la Pena de Muerte

- Como mencioné antes, la pena de muerte ha disminuido en los Estados Unidos debido a la política de la era de la recesión. La administración de la pena de muerte, junto con los litigios, es muy cara. Durante el crisis financiero, muchos estados abolieron la pena de muerte o dejaron de usarla.

- Trump ha sido un admirador público de la pena de muerte desde la década de 1980, cuando publicó enormes anuncios en los periódicos pidiendo la pena de muerte en varios casos, incluyendo el célebre caso de cinco adolescentes acusados de acostar a una corredora en el Parque Central de Nueva York. Lo increíble es que los cinco fueron exonerados por evidencia de ADN, pero Trump continúa hasta el día de hoy argumentando que eran culpables y merecían la pena de muerte.

- Aún ahora, en los últimos días de su administración, Trump y Barr continúan a ejecutar a personas condenadas a muerte en el nivel federal, incluyendo personas con discapacidades mentales y trauma personal documentado y personas que muchos expertos creen que son inocentes.

- Interviniendo en la Justicia Local

- A pesar de que la administración de Trump no tenía jurisdicción en asuntos estatales, Trump intervino, a través de Twitter, en los procedimientos locales cuando fueron simbólicamente útiles para él.

- Un ejemplo fue la muerte de una joven llamada Kate Steinle en San Francisco. Un inmigrante indocumentado fue acusado del crimen. Resultó que había encontrado un arma perdida por un agente del FBI y el arma falló. El acusado fue absuelto. A lo largo del juicio, Trump atribuyó el resultado a los “valores de San Francisco” y lo utilizó para criticar las “ciudades santuario”, que tenían una política de no cooperar con las agencias federales de inmigración.

- Obstrucción de la Justicia contra los Poderosos

- Es instructivo comparar estas políticas punitivas hacia las comunidades marginadas con la obstrucción de la justicia orquestada por la administración Trump en lo que respecta al propio Trump y sus leales.

- Trump usó repetidamente el poder del perdón para excusar a sus amigos y asociados, acusados o condenados por crímenes atroces, más recientemente, Michael Flynn.

- La investigación del fiscal especial Robert Mueller sobre la interferencia rusa en las elecciones de 2016 encontró que los funcionarios de la campaña de Trump eran receptores entusiastas de la inteligencia rusa y que los miembros de la campaña de Trump, incluido el propio Trump, obstruyeron la justicia en este contexto en al menos diez casos.

- Cambios en la Corte Suprema

- Pero quizás el efecto más duradero de la administración Trump en la justicia penal son sus tres nombramientos en la Corte Suprema.

- Neil Gorsuch fue designado para un escaño que quedó vacante durante la era de Obama, pero fue arrebatado por los republicanos argumentando que un presidente en su ultimo año no debería nombrar a un suplente.

- Despues, Trump tuvo otra oportunidad a nombrar a un juez supremo y nombró a Brett Kavanaugh, cuyo proceso de solicitud se vio empañado con una acusación creíble de abuso sexual. Los votos a favor y en contra de su nombramiento fueron de partidos políticos.

- Finalmente, tres semanas antes de las elecciones, falleció la jueza ruth bader ginsburg, lo que les dio a los republicanos la oportunidad de hacer exactamente lo que impidieron hacer a los demócratas al final de la presidencia de Obama: nombrar a una jueza más, Amy Coney Barret.

- El nuevo tribunal es incondicionalmente conservador en varios asuntos de justicia penal. Seis jueces apoyan la pena de muerte y los tres nuevos jueces tienen un historial de imponer largas penas de prisión. En asuntos relacionados con las investigaciones policiales basadas en tecnología, sin embargo, Gorsuch podría votar más a la izquierda que sus dos nuevos colegas.

- El Futuro Penal de la Administración Biden

- Los partidarios de la reforma de la justicia penal se sintieron aliviados con los resultados de las elecciones, aunque están mucho más cerca de lo que se esperaba y el control del Senado aún no se ha determinado.

- Es importante recordar que la justicia penal sigue siendo principalmente un asunto local. Las reformas que apoyan la igualdad racial y erosionan la guerra contra las drogas todavía ocurrirán en los estados azules, excepto que ahora, el aspecto federal de la guerra contra las drogas probablemente volverá a la moderación que caracterizó a la administración Obama.

- Otros cambios federales podrían involucrar recortes presupuestarios a los departamentos de policía municipales, que apoyarán muchas iniciativas locales de desviar los problemas sociales a agencias no policiales.

- El desafío más complicado involucra cambios en la Corte Suprema. Una posibilidad, que no está prohibida por la ley, es que Biden amplíe la Corte y nombre siete jueces progresivos para equilibrar la composición conservadora de la corte. El problema con este enfoque es el riesgo de que el tribunal pierda la legitimidad que le queda, y que una futura administración republicana nombrará a 14 jueces, etc., etc. Pero los partidarios progresistas de Biden lo presionarán para que lo haga, en parte porque se han adoptado enfoques más cuidadosos se encontró con ofuscación y manipulación durante los últimos cuatro años. Sin embargo, si el Senado permanece en manos republicanas, Biden tendrá dificultades para tener éxito con estas nominaciones.

Fixing Policing Is More Complicated than Cutting Budgets

One of the defining features of the last election was the passage of a slew of propositions diverting funds away from the police department. Inspired by the vocabulary of movements (defund! abolish! dismantle!) but not always referencing this vocabulary explicitly, these propositions aimed at shifting the approach toward addressing social problems toward social services, mental health, and harm reduction approaches to narcotics.

But it turns out that things are more complicated than expected. The Chronicle’s Bob Egelko reports today:

As homicides rise throughout the Bay Area during the coronavirus outbreak, San Francisco police have reported 45 killings this year, compared with 41 for all of 2019. Black people, who make up less than 6% of the city’s population, accounted for nearly half the victims.

The 41 slayings reported in 2019 were San Francisco’s lowest total in 56 years. Police reported four homicides in January and February this year, but the numbers began to rise as the pandemic set in, even as most other crimes were declining. As residents grow more fearful, gun sales are also increasing and have reached record levels nationwide.

Homicides in the Bay Area’s 15 largest cities increased by 14% in the first six months of 2020 compared with 2019, The Chronicle has reported. In Oakland, with a population of 435,000 compared with San Francisco’s 896,000, killings totaled 79 as of mid-October, a 36% increase over 2019.

The homicide totals do not include any fatal shootings by police.

In San Francisco, police said, the victims of the year’s first 43 homicides included 20 Blacks, seven Latinos or Latinas, seven Asian Americans and six non-Hispanic whites, with the rest from other groups. The two most recent killings, a double homicide Nov. 18, are still under investigation, police said.

Indeed, the trend is the same in Oakland, and the political implications are too important to ignore. Earlier this month, Rachel Swan reported:

Heeding the urgency of the Black Lives Matter movement, Oakland leaders committed over the summer to ultimately slash the Police Department’s budget in half, by about $150 million. The City Council created the 17-member Reimagining Public Safety Task Force to figure out how to meet this lofty goal to “defund the police.” They would write a draft proposal by December and present it to the council in March.

Then a wave of gun violence engulfed the flatlands in East Oakland, home to the city’s most impoverished neighborhoods. Homicides spiked. Policymakers — and even the most devoted reformers — had to confront a paradox: that the Black and Latino neighborhoods most threatened by police violence are also the ones demanding better and more consistent law enforcement.

Task force members agreed that police brutality against Black and brown people is too common, that gun violence needs to end and that the city needs more services to address the underlying causes of crime. But while advocates wanted swift, dramatic change, others felt conflicted. In neighborhoods with high crime and slow police response times, Black residents winced at what sometimes felt like preaching from outsiders.

A poll released last week by the Chamber of Commerce showed that, citywide, 58% of residents want to either maintain or increase the size of the police force. That figure climbs to 75% in District 7, an area of East Oakland where gunfire exploded this summer.

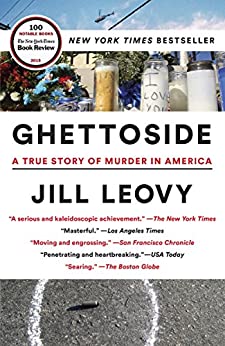

The reason I get a rash every time I hear the defund/abolish/dismantle refrain is that, years ago, I realized the fundamental problem with American policing: it’s not about too much or too little policing, it’s about the wrong kind of policing. I got there in three parts. First, I read Alexandra Natapoff’s fantastic article Underenforcement, which theorized the problem of too little policing and why it affects especially the neighborhoods where people assume there’s too much policing going on. Then, I read an interview with the wonderful David Simon, who spent the earlier part of his career as a crime reporter following the Baltimore homicide detectives (and writing this marvelous book.) He explained why the reward system for police officers incentivized stop-and-frisk policing and disincentivized crime solving:

How do you reward cops? Two ways: promotion and cash. That’s what rewards a cop. If you want to pay overtime pay for having police fill the jails with loitering arrests or simple drug possession or failure to yield, if you want to spend your municipal treasure rewarding that, well the cop who’s going to court 7 or 8 days a month — and court is always overtime pay — you’re going to damn near double your salary every month. On the other hand, the guy who actually goes to his post and investigates who’s burglarizing the homes, at the end of the month maybe he’s made one arrest. It may be the right arrest and one that makes his post safer, but he’s going to court one day and he’s out in two hours. So you fail to reward the cop who actually does police work. But worse, it’s time to make new sergeants or lieutenants, and so you look at the computer and say: Who’s doing the most work? And they say, man, this guy had 80 arrests last month, and this other guy’s only got one. Who do you think gets made sergeant? And then who trains the next generation of cops in how not to do police work?

Then, I read Jill Loevy’s heartbreaking Ghettoside. Loevy shows how the LAPD homicide detectives are unable to solve murders because witnesses won’t cooperate with them. What she says at the outset of the book (pp. 8-9) is so powerful, and so easy to obfuscate, that it calls for a long quote.

This is a book about a very simple idea: where the criminal justice system fails to respond vigorously to violent injury and death, homicide becomes endemic.

African Americans have suffered from just such a lack of effective criminal justice, and this, more than anything, is the reason for the nation’s long-standing plague of black homicides. Specifically, black America has not benefited from what Max Weber called a state monopoly on violence the government’s exclusive right to exercise legitimate force. A monopoly provides citizens with legal autonomy, the liberating knowledge that the government will pursue anyone who violates their personal safety. But slavery, Jim Crow, and conditions across much of black America for generations after worked against the formation of such a monopoly where blacks were concerned. Since personal violence inevitably flares where the state’s monopoly is absent, this situation results in the deaths of thousands of Americans each year.

The failure of the law to stand up for black people when they are hurt or killed by others has been masked by a whole universe of ruthless, relatively cheap and easy “preventive” strategies. Our fragmented and underfunded police forces have historically preoccupied themselves with control, prevention, and nuisance abatement rather than responding to victims of violence. This left ample room for vigilantism—especially in the South, to which most black Americans trace their origins. Hortense Powdermaker was among a handful of Jim Crow–era anthropologists who noted that the Southern legal system of the 1930s hammered black men for such petty crimes as stealing and vagrancy, yet was often lenient toward those who murdered other blacks. In Jim Crow Mississippi, killers of black people were convicted at a rate that was only a little lower than the rate that prevailed half a century later in L.A.—30 percent then versus about 36 percent in Los Angeles County in the early 1990s. “The mildness of the courts where offenses of Negroes against Negroes are concerned,” Powdermaker concluded, “is only part of the whole situation which places the Negro outside the law.” Generations later, far from the cotton fields where she made her observations, black people in poor sections of Los Angeles still endured a share of that old misery.

This is not an easy argument to make in these times. Many critics today complain that the criminal justice system is heavy-handed and unfair to minorities. We hear a great deal about capital punishment, excessively punitive drug laws, supposed misuse of eyewitness evidence, troublingly high levels of black male incarceration, and so forth. So to assert that black Americans suffer from too little application of the law, not too much, seems at odds with common perception. But the perceived harshness of American criminal justice and its fundamental weakness are in reality two sides of a coin, the former a kind of poor compensation for the latter. Like the schoolyard bully, our criminal justice system harasses people on small pretexts but is exposed as a coward before murder. It hauls masses of black men through its machinery but fails to protect them from bodily injury and death. It is at once oppressive and inadequate.

The crux of the matter is something that has been tragically true for decades, but “my side” of the criminal justice debate is always too reticent to mention: African American people–the people whom “defund” initiatives are purporting to protect–are vastly overrepresented as both homicide perpetrators and victims. Time after time I see mental and linguistic gymnastics in academic and journalistic circles pretzeling around this simple, true statistic (note the quotes above from solid, responsible journalists, focusing only on victimization.) I know there are good intentions behind this–the fear to stereotype–and I also know there are performative reasons: in the era of Kendi and DiAngelo reeducation camps in our campuses, no one wants to appear racist. We are repeatedly admonished that asking the right question (“what about black-on-black crime?”) is in itself racist, so how are we ever going to get any answers? The thing is, there is an obvious explanation for this, and it’s not racist at all: When one lives in poverty and is consistently treated as a second class citizen, and when legitimate opportunities to thrive are not available, a larger proportion of the population will recur to illegitimate ones.

This is so obvious that everyone I speak to behind bars, when reflecting about their own lives and how they ended up in prison, say the same thing: recurring to violence as part of the drug trade is situational and comes from a very diminished repertoire of opportunities and choice. As James Forman explains here, is much easier for “my side” of the debate to focus on drug offenses, where we know that white and black people use and sell at about the same rates, and explain the disparities by overactive stop-and-frisk policing. But what do we do about explaining disparities in violence? Overpoliced poor neighborhoods do not explain disparities in bodies on the ground. It was therefore eye opening to read Scott Jacques and Richard Wright’s Code of the Suburb. In a shorter article, Jacques and Wright explain why it is that suburban, middle-class, white drug dealers don’t get mixed up in homicides: not only were they raised in the conflict-avoiding “code of the suburb”, but they knew that they had bright futures ahead of them and the stakes were too high:

Compared to their urban counterparts, it was easier for the suburban dealers to give up dealing because they didn’t really need the money. Their parents were able to provide for them, so for these teens, dealing was never meant to be a career. It was just another phase on their way to becoming successful adults, which they had no intention of jeopardizing.

In the 1950s, studying juvenile crime was all the rage among criminologists. One promising avenue was the opportunity theory developed by Cloward and Ohlin. They argued that the kind of crime one recurs to–not only whether or not one starts engaging in criminal activity–depends on what kind of opportunities are available in one’s neighborhood in terms of resources, know-how, role models, etc. Some of my colleagues have made a name for themselves trashing Cloward and Ohlin and retroactively branding their theories as racist (again, following the principle that any focus on crime committed by people of color that does not explain it away as discriminatory policing is racist.) The effort to take what was a solid step forward and rebrand it as reactionary and outside the realm of the sayable reminds me of Mark Twain’s saying, “the radical of one century is the conservative of the next. The radical invents the views. When he has worn them out, the conservative adopts them.” But if you read Jacques and Wright, you have to conclude that, in basics, what Cloward and Ohlin said was so spot-on that it still stands: the same systemic racism that produces discriminatory policing also produces differences in violent crime perpetration rates. And the tragedy is that, no matter how you look at it, it’s poor people of color who lose. They are hounded and humiliated by paint-by-numbers policing that doesn’t solve crimes, they are themselves victimized by violent crime at higher rates, and because their uphill battles are not solved from the root in this uncaring, hypercapitalist society, they also recur to crime at higher rates. All these things come from the same roots, but somehow saying the first two is fine, while saying the third out loud runs the risk that your colleagues will treat you as if you have cooties.

I think we’re seeing a refreshing change, though, and more folks–like Simon, Loevy, Forman, Pfaff, Jacques and Wright, and Natapoff are willing to point out that the problems caused by poverty and deprivation cannot be brushed away just because it’s inconvenient to discuss them. Recently, they have been joined by David Garland, whom no one can suspect of being some sort of right-wing reactionary nut. Lisa Kerr summarized the main points in the following tweet thread:

As always, fascinating keynote from David Garland at @CCR_UofA Prisons and Punishment conference this morning. He started by making clear that we should not avoid fact of racial difference in homicide / violent crime rates in the US (in both commission and victimization).

Conservatives repeat and liberals avoid this data – but that’s a mistake. These real differences have nothing to do with intrinsic characteristics. Must ask: how does this fact pattern emerge? Segregation, economic exclusion, absence of social services, deep poverty.

Garland is also clear that policing operates in a more dangerous environment in the US than in other countries, due to guns. Police at work are killed at a higher rate, as are civilians by police.

Central claim was that the relaxation of Democratic commitment to economic politics, after New Deal, in favour of identity politics, has had bad effects. Plus: we should spend more time calling for economic justice, less time calling for defunding police / abolishing prisons.

Garland says that “Defund Police” is “a slogan that can’t mean what it says.” No modern nation has abolished police, would mean (1) private security for rich (2) poor communities exposed and vulnerable.

We should be saying “Defund the Rich.” Tax more to fund police, fund social services and safety net, and transform the police: abolish militarization and improve accountability mechanisms.

Notably, someone asked, can’t we do ‘all of the above’? Garland is firm that “Defund Police” is very ill-conceived and has benefited Republicans, even as Democrats worked hard to distance themselves from it.

These tweets don’t do the talk justice. Be sure to watch. (I was transported back to graduate school when I had the ridiculous good fortune to learn from Garland for several years. I have craved his perspective even more in these difficult months.)

Watch the whole thing:

What we need is not more policing or less policing. We certainly don’t need slogans. What we need is to rethink the very nature of policing and rebuild policing from the ground up. How we promote and reward police officers must change to disincentivize stop-and-frisk abuses and incentivize crime solving–for everyone’s sake.

Essential Readings for CCC3: COVID-19 Meets Mass Incarceration

In anticipation of our upcoming symposium about COVID-19 and mass incarceration, here are a few sources that our attendees might like to read. It’s not an exhaustive list; rather, it focuses on some of the themes we will be covering throughout the symposium.

Prisons, Disease, Medicine

Ashley Rubin, Prisons and jails are coronavirus epicenters – but they were once designed to prevent disease outbreaks, The Conversation, April 15, 2020

Misha Lepetic, Foucault’s Plague, 3 Quarks Daily, March 4, 2013

Margo Schlanger, Plata v. Brown and Realignment: Jails, Prisons, Courts, and Politics, Harvard Civil Rights–Civil Liberties Law Review 48(1) 2013: 165-215.

Osagie Obasogie, Prisoners as Human Subjects: A Closer Look at the Institute of Medicine’s Recommendations to Loosen Current Restrictions on Using Prisoners in Scientific Research, Stanford Journal of Civil Rights & Civil Liberties 6(1) 2010: 41.

COVID-19 In Prisons

Brendan Saloner, Kalind Parish, Julie A. Ward, Grace DiLaura, Sharon Dolovich, COVID-19 Cases and Deaths in Federal and State Prisons, JAMA, July 8, 2020

Hadar Aviram, Triggers and Vulnerabilities: Why California Prisons Are So Vulnerable to COVID-19, and What to Do About It, Tropics of Meta, July 3, 2020

Hadar Aviram, California’s COVID-19 Prison Disaster and the Trap of Palatable Reform, BOOM California, August 10, 2020

Sharon Dolovich, Mass Incarceration, Meet COVID-19, University of Chicago Law Review Online, Nov. 2020

Matthew J. Akiyama, M.D., Anne C. Spaulding, M.D., and Josiah D. Rich, M.D., Flattening the Curve for Incarcerated Populations — Covid-19 in Jails and Prisons, The New England Journal of Medicine, May 2020

Oluwadamilola T. Oladeru, Nguyen-Toan Tran, Tala Al-Rousan, Brie Williams & Nickolas Zaller, A Call to Protect Patients, Correctional Staff and Healthcare Professionals in Jails and Prisons during the COVID-19 Pandemic, Health and Justice, July 2, 2020

The San Quentin Catastrophe

Megan Cassidy and Jason Fagone, 200 Chino inmates transferred to San Quentin, Corcoran. Why weren’t they tested first? San Francisco Chronicle, June 8, 2020

AMEND SF and UC Berkeley, Urgent Memo – COVID-19 Outbreak: San Quentin Prison, June 15, 2020

Megan Cassidy, San Quentin officials ignored coronavirus guidance from top Marin County health officer, letter says, San Francisco Chronicle, August 11, 2020

Al Jazeera Front Lines, Pandemic in Prison: The San Quentin Outbreak, October 28, 2020

In re Von Staich on Habeas Corpus, A160122, California Court of Appeal for the First District, October 20, 2020

Solutions and Policies

Hadar Aviram, Gov. Newsom’s Release Plan Is Not Enough, San Francisco Chronicle, July 10, 2020

James King and Danica Rodarmel, Gov. Newsom must release more people from prisons to protect Californians and save lives, The Sacramento Bee, July 11, 2020

Jason Fagone, California could cut its prison population in half and free 50,000 people. Amid pandemic, will the state act? San Francisco Chronicle, August 16, 2020

Ruth Wilson Gilmore in conversation with Naomi Murakawa, Haymarket Books, April 17, 2020

Reproductive Justice, Women, and Gender in CA Prisons

Sulipa Jindia, Belly of the Beast: California’s dark history of forced sterilizations, The Guardian, June 30, 2020

Jason Fagone, Women’s prison journal: State inmate’s daily diary during pandemic, San Francisco Chronicle, June 14, 2020

Valerie Jenness, Transgender Prisoners in America, September 5, 2016

AJ Rio-Glick, COVID-19 Adds to Challenges for Trans People in California’s Prisons, Vera Institute of Justice Blog, July 7, 2020

COVID-19 in Immigration Detention Facilities

COVID-19 in Jails, Prisons, and Immigration Detention Centers: A Q&A with Chris Beyrer, Johns Hopkins School of Public Health, September 15, 2020

American Bar Foundation, Impact of COVID-19 on the Immigration System

Carmen Molina Acosta, Psychological Torture: ICE Responds to COVID-19 with Solitary Confinement, The Intercept, August 24, 2020

COVID-19 Prevention in Prisons and the Problem of Buy-In

Throughout the last few months, there’s something that’s been constantly gnawing at me and I haven’t had a moment to process in an organized way. I started thinking about this a lot when the AMEND report came out in June, reporting that people at San Quentin were afraid to get tested or report symptoms, lest they be placed in isolation in a death row or solitary confinement cell. And it came up again when I listened to the Assembly hearing on the PPE wearing failure and the commentary about the “physical plant” being “not conducive to compliance.” Then, I thought about it again when I read the AG’s briefs yesterday, detailing all the “reasonable” COVID-19 prevention steps they took. And finally, I felt a sense of despair and futility when I read this well-intended missive from Brendon Woods:

Unpopular view but incarcerated people should be amongst the first to get a safe vaccine. You can’t socially distance in prison or jail. Our society has failed them too many times, we should not do it again. We will be judged by how we treat our most vulnerable #CareNotCages

— Brendon Woods (@BrendonWoodsPD) November 13, 2020

My immediate, gut reaction to the idea of vaccination priority was this: If I were incarcerated in one of the places that experienced horrific outbreaks–or anywhere else in CA, really–why would I believe anyone from CDCR or CCHCS offering me a vaccine, treatment, PPE, quarantine space, transfers, or anything else, except a ticket out of the system? And why on earth would I want to cooperate with anything short of being released? The sense of futility comes from a strong core realization that the trust between the state and incarcerated people is so deeply broken that, even when reasonable steps are being proposed, they’ll be understandably doubted. The long history of being swindled and harmed, especially in the context of healthcare, is so embedded in the system’s DNA, that any prevention or treatment initiative must take into account poor buy-in.

I’m not a doctor or a public health expert, but it seems obvious to me that, when designing a public health response, one important consideration is public buy-in. As this paper explains, effective COVID-19 prevention measures depend, in big part, on an enormous amount of groundwork to foster compliance, including virtual community building, fostering solidarity between high-risk and low-risk groups, and trust building between decision-makers, healthcare workers, and the public. What we’ve seen in the U.S. on the national level is instructive of what happens when the government not only fails to make this effort, but actively stokes the opposite sentiments. I suspect that even a reasonable administration would have had trouble containing the virus in such a big country with deep pockets of ignorance and misinformation, but given the Trumpian legacy of actively creating misinformation and division, this is going to be a huge challenge for whoever runs the COVID-19 response for the Biden administration.

What we’re seeing in CDCR facilities is a crystallized example of this problem. Efforts to implement pandemic prevention methods have to contend with deep mistrust of prison authorities in general, and prison healthcare in particular, which have profoundly painful historical roots. Osagie Obasogie reminds us of the horrific history of harm and deception in prison healthcare in this piece:

As early as 1906, Dr. Richard P. Strong—director of the Biological Laboratory of the Philippine Bureau of Science who later became a professor of tropical medicine at Harvard—gave a cholera vaccine to twenty-four Filipino inmates without their consent in order to learn about the disease; thirteen died. Though this provides an early modern example of using prisoners as human subjects, it certainly was not the last. Twelve inmates from Mississippi’s Rankin Farm prison became test subjects in 1915 to study pellagra—a disfiguring and deadly disease characterized by skin rashes and diarrhea. Though common wisdom at the time suggested that pellagra was a disease caused by germs, Dr. Joseph Goldberger—a physician in the federal government’s Hygienic Laboratory, predecessor to the National Institutes of Health—thought it was linked to malnutrition characteristic of Southern rural poverty. After Mississippi Governor Earl Brewer promised pardons to all participants—an inducement to participate in research that would be intolerable today–Goldberger tried to prove his theory that poor diet caused pellagra by subjecting inmates to what many called a “hellish experiment”: eating exclusively high-starch foods such as “corn bread, mush, collards, sweet potatoes, grits and rice” that caused considerable pain, lethargy, and dizziness. Despite their pleadings to end the study, prisoners were not allowed to withdraw. And, in an early 1920s experiment that was as bizarre as it was gratuitous, 500 inmates at California’s San Quentin prison had testicular glands from rams, boars, and goats implanted into their scrotums to see if their lost sexual potency could be rejuvenated.

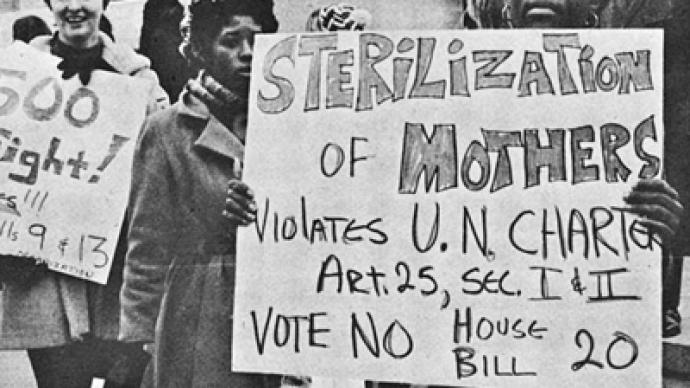

But one needn’t go that far back. Nonconsensual sterilization of incarcerated women was still going on as of 2013, when the practice was exposed and excoriated. The Guardian’s Shilpa Jindia explains:

Despite federal and state law prohibiting the use of federal funds for sterilization as a means of birth control in prisons, California used state funds to pay doctors a total of almost $150,000 to sterilize women. That amount paled in comparison to “what you save in welfare”, one doctor told the news outlet.

Against this backdrop, you would expect public health experts at CDCR to bend over backwards to build trust, so as to engender cooperation. Instead, they’ve done exactly the opposite. The most obvious problem, of course, has been the botched transfer from CIM. I can finally put my finger on what seemed so disingenuous in the AG’s brief from yesterday: “[P]etitioners’ attempts to suggest prisoner transfers of any kind are not safe or effective is not well taken.” The irony of taking offense at people’s understandable mistrust after this colossal fiasco is completely lost on them, which I find breathtakingly obtuse.

But the transfer issue is just one of many. Why would prisoners comply with PPE-wearing requirements when they see guards, frequently and openly, flouting these requirements with no consequences? Why would people rush to report symptoms and get tested when the consequence is that they’ll be put in places which they’ve associated, for decades, with punishment and deprivation? Most importantly, given the history of using prisoners as experiment subjects, how could CDCR and CCHCS possibly lay some trust groundwork when rolling out a vaccine, so that people don’t suspect them, understandably, of subjecting them to untested, unreliable treatments?

This is the real crux of the problem. It’s not that “the physical plant is not conducive to compliance.” It’s that the atmosphere of neglect, indifference, and cruelty, and the resulting deep mistrust, does not engender compliance, and at every turn in this situation, prison authorities have moved the compliance needle further out of whack. This problem is a big part of why the only way out is to release people. Whatever other preventative steps the authorities are taking, regardless of their objective usefulness, need to actually be adopted by people on the ground to succeed. Hanging informational posters and handing out masks might work with some fantasy environment in mind, but it doesn’t work with the institutions and people we actually have. And it doesn’t seem like the AG’s office, or CDCR officials, have even begun to comprehend the depth of this problem.

Post-Election Thoughts

The Scorpion and the Frog

The results of the election did not bring me immediate solace. I’m sure this has been the case for many folks who found it difficult to take off the psychological backpack we have been carrying for so long. In my case, the psychological weight is the product of daily engagement with this administration on various public forums, including having to spend least thrice a week, WEEKLY, for the last four years, in TV stations and radio studios talking about this. In November 2016, when I lost the fight for death penalty abolition and my beloved cat Spade on the week of the election, I made it my mission to be an expert in everything these cartoon villains were cooking up, and every morning I sat up abruptly in my bed, with my first thought being, “it’s already morning in D.C., what has he done today?” Every time I saw an unrecognized number on my phone it was a TV producer or journalist asking me things that I had to cram on. I’ve crawled through information on abominable, underhanded things that I could not have even imagined possible before the last four years. Engaging with this sewer of an administration every day, including weekends, has brought exhaustion and stress into our family life, soured my good humor and my patience at work, and taken a real, measurable toll on my health. Doing upbeat explainers, volunteering, and taking abuse via phone and text from voters has felt like wading through a swamp, and even though I wore my psychological hip waders, I resent and revile this administration for demanding that I set aside my own grief, decency, and decorum, and be constantly on-call to respond to venal, opportunistic excrement. After I gave the explainer on Justice Ginsburg’s replacement process, I could barely get out of bed for a few days.

But the miasma in my soul is slowly dissipating. The first time I felt truly rapturous was when I got a letter from Traci Felt Love, the organizer of Lawyers for Good Government. The letter reminded me of when we started L4GG and brought back the incredible week in which we shut down San Francisco International Airport in reaction to the Muslim ban. It was only then that the magnitude of our success in dethroning this monster started to hit me, and I’ve been slowly digesting it.

One thing that has greatly helped is ignoring the legal pageant of the absurd that Trump is mounting in various courts around the country. I have given myself permission to disengage from all his frivolous lawsuits, antics, last-minute personnel juggling, and desperate cries for attention. In January, no matter what happens in the interim, Joe Biden will be President of the United States. Whether Trump concedes (ya think?), resigns (hmmmm), flees to the Cayman Islands to a mansion with golden toilets (on brand) or is dragged out of the White House in handcuffs (appealing but dangerous), the outcome will be a change in administrations.

It’s useful to keep in mind the story of the scorpion and the frog. A scorpion, which cannot swim, asks a frog to carry it across a river on the frog’s back. The frog hesitates, afraid of being stung by the scorpion, but the scorpion assures the frog he won’t do that: “If I sting you, we’ll both drown, right?” This argument convinces the frog, which agrees to transport the scorpion. Midway across the river, the scorpion stings the frog anyway, dooming them both. The dying frog asks the scorpion why it stung despite knowing the consequence, to which the scorpion replies: “I couldn’t help it. It’s in my nature.”

Trumps are going to Trump. Giulianis are going to Giuliani. McConnells are going to McConnell, with or without us as their audience. It’s far more productive to focus our attention on the upcoming races in Georgia.

Drug Truce

Throughout the country, drug law reform gained more momentum. This wonderful post on the Drug Policy Alliance blog summarizes some of the main reforms, the most impressive of which was Oregon’s approval of Measure 110. The next step in procuring a truce on drugs was always going to be branching beyond marijuana, and for various political reasons that are difficult to explain to people outside California, I expected another state to move in that direction first.

What I find especially thrilling about the passage of Measure 110 is that it could open the door to an important dialogue about the value and benefits of psychedelics. MAPS has been leading the charge on declassifying these important substances and acknowledging their potential to help people with depression and trauma, as well as foster spiritual growth. Little by little, the hypocrisy is dissipating, but it’s going to happen on the state and local level first.

When the Perfect Is the Enemy of the Good

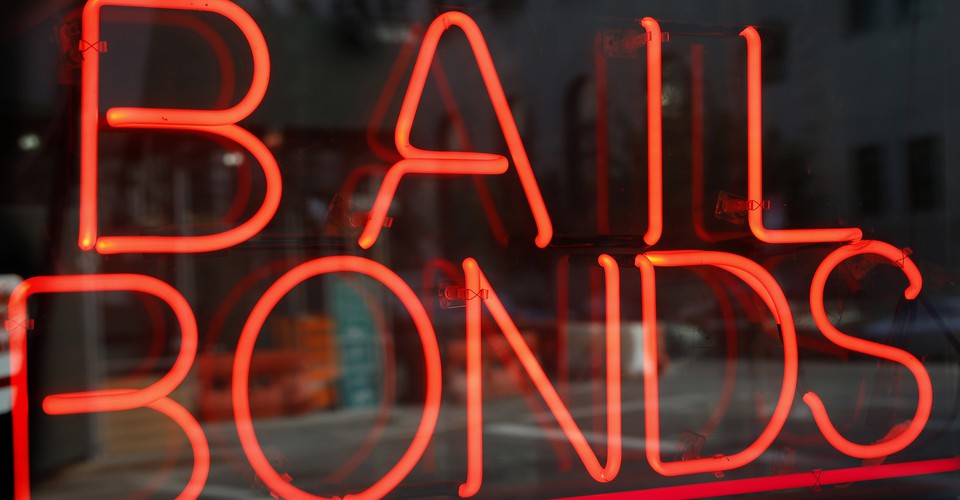

Amidst my joy about the passage of Prop 17 and the failure of Prop 20–a reactionary law-and-order package–the demise of Prop. 25 brought me some anguish. As I explained elsewhere, all the arguments against the abolition of cash bail were ridiculous except for one, which had superficial appeal: the idea that “algorithms are racist” and that we would end up with “something worse” than cash bail. Aside from the fact that it’s hard to imagine how risk assessment is “worse” than debtor prisons straight out of a Charles Dickens novel, there’s a basic misunderstanding of how algorithms work. I have been explaining and explaining, but for some reason am not getting through to people captivated by woke rhetoric: ALGORITHMS ARE NOT RACIST. They predict the future on the basis of the past. If they have racially disparate outcomes, it’s because they reflect a racist reality in which, for a variety of systemic, sad, and infuriating reasons, people who are treated like second-class citizens in their own country commit more violent crime. The overrepresentation of people of color in homicide offenses and other violent crime categories is not something that progressives like to talk about, but it is unfortunately true–not just a mirage caused by stop-and-frisk in low-income communities. The reasons why more African American people commit more homicides than white people are the same reasons why they are arrested more frequently for the drug offenses they don’t actually commit more than white people: deprivation, neglect, lack of opportunities, dehumanization and marginalization on a daily basis. Solving these problems requires an administration committed to treating its citizenry fairly, not sweeping them under the rug by ignoring predictive tools that show what is actually going on. So powerful is the progressive self-deception that the ACLU, initially a supporter of eliminating cash bail, opted not to have a position on the ballot, because of the optics. I can’t even begin to tell you how many people I like and respect opposed Prop 25 using organizations’ positions as proxy, as if they couldn’t think for themselves. These organizations’ and people’s fears of being perceived as racists by supporting “algorithms,” the bogeymen of the left, was so overpowering that it hijacked the very real possibility to get rid of an actual, real, on-the-ground, in-the-open perversity: the only-in-America notion that people should pay money for their pretrial release.

The counterargument, made by some thoughtful folks, was that rejecting Prop. 25 would lead to a better proposal to abolish cash bail. But this argument exhibits deep ignorance of how political gains are made. Part of why I’m so upset about this is that I’ve already lived through a horrible round of the Perfect-Is-the-Enemy-of-the-Good game. Back in 2016, when we campaigned for death penalty abolition, I had to respond to arguments by progressives who thought that abolishing the death penalty was going to somehow “retrench” life without parole. The preciousness of this view infuriates me. As I explained until I was blue in the face, political progress is made incrementally. You can’t get to LWOP abolition without death penalty abolition. Expecting ballot propositions, which have to rely on broad coalitions, to be tailor-made to one’s exquisitely purist views about the public good is a recipe for disappointment. And, as Gov. Newsom said, the demise of Prop 25 essentially eliminates any possibility, motivation, or energy for getting together the “more perfect” solution to the bail problem that activists are yearning for. So, instead of celebrating the end of cash bail, progressives have yet again been duped into failing their own cause because the compromise wasn’t photogenic enough for them, and the big winner has been the bail bonds industry–you can see in this piece how effectively these scoundrels have coopted wokespeak to keep Victorian debt prisons alive.

Got a Sane Idea? Great! Wrap It in Sane Packaging

Just read a terrific Mother Jones article, which highlights the success of various local initiatives to divert resources from policing to less confrontational alternatives. Beyond my satisfaction with this outcome, I’m pleased with the rhetorical strategy used in these initiatives.

In the aftermath of the killing of George Floyd, many advocates were making proposals that sounded scary, because they were wrapped in odious movement jargon (defund! abolish! dismantle!). Thing is, the proposals themselves were not radical or insane; they were sane enough that even people who were victimized in scary ways could see the logic in them–if they had the background to understand them. Alternatives to policing are not earth-shattering discoveries. Anyone, not just hyperprogressives, who walks around the Tenderloin these days can sense the palpable shift in energy since the arrival of the wise and conciliatory Urban Alchemy folks. All these propositions are doing is rolling back the Nixonian logic, according to which you somehow get more justice if there are more cops, riot gear, and weapons on the streets. We were sucked into this insanity in the 1970s with the LEAA funding scheme, and later in the 1980s with civil asset forfeiture. You could be forgiven for thinking that “defunding the police” is an extreme proposal if you’re not familiar with how police departments used to be run before they became bloated paramilitary organizations.

But the success of this measures was not only rooted in their inherent reasonableness (and cost-effectiveness.) It was rooted in wise, matter-of-factly packaging, which offered positive alternatives to policing that people could get behind. There is an important lesson here for progressives looking for referendum victories, which I very much hope will be learned: packaging matters. Offering people a realistic vision of humane, therapeutic, preventative public safety works better than wrapping sane, totally plausible ideas in flurries of self-righteous performativity. And that means resisting the cultural zeitgeist, which pushes the movement to flood social media with the most preposterous, off-putting jargon, even when proposing things that would appeal to a broad swath of the population.

When incendiary terminology is used to explain sane, effective reform, more time is spent debating the terminology and performatively defending it than discussing the policies themselves. People who are put off by the rhetoric are exhorted to “check the website,” “do the work,” and “educate themselves” by folks who do not inspire any desire to engage any further with them or with their ideas. Indeed, one of the dumbest aphorisms of this movement is the classic “it’s not my job to educate you.” It’s nobody’s job to educate anyone else (except, in the case of teachers, their actual students.) But hurling insults and disdain on people, piling nonrequired homework on their backs, hiding good ideas behind performative nonsense, and finding fault in people asking to know what they’re expected to support and vote for, is not particularly likely to induce them to take the trouble to learn somewhere else. Decrying the burden of “unpaid emotional labor,” another unfortunate classic, is also not particularly persuasive. Not everyone needs to dance through their revolution like Emma Goldman, but very few people want to get flogged through it. Corollary: If you call yourself an activist, and you want to bring people to your coalition, yes, it is part of your job to educate them. I’m so pleased that the advocacy for these proposals took a different approach, one that voters could get behind. The result will be safer and happier streets in many U.S. cities.

The Marshall Project Survey and “Programspeak”

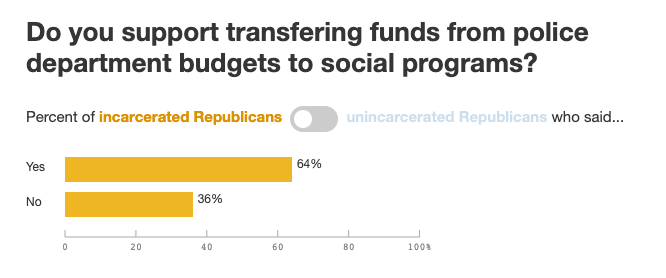

The Marshall Project has published the results of a political survey of incarcerated people, and they are extremely interesting. In a previous installment, they refuted the widely-held belief in broad support for Democrats behind bars; the majority of white prisoners would vote for Trump if they could. The current installment, in which the respondents were invited to opine on criminal justice policy, is just as interesting. Among other findings, even though there was a marked racial divide on questions about police violence and support for Black Lives Matter, 64% of incarcerated Republicans supported transferring funds from policing to social programs, by contrast to only 5% of incarcerate Republicans.

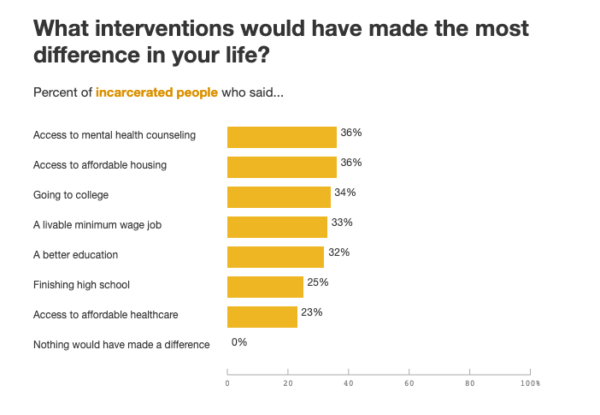

I highly recommend reading the whole thing, and have just one comment to make. In the survey, respondents were invited to comment on the kinds of interventions that would have kept them from prison, and they did list some of the “usual suspects”:

But the article then comments that many respondents ascribed the responsibility for their incarceration solely to their own behavior.

This is worth commenting on, because it dovetails with one of my findings fromYesterday’s Monsters, namely, the insidiousness and proliferation of “programspeak.” Programspeak is more than a jargon–it’s a worldview that is propagated in prison rehabilitative programming, all of which is geared toward telling the parole board a story of personal responsibility. At parole hearings, where the concept of “insight” is kind, there is a constant pressure on people to attribute their incarceration only to their own failings, without any allowance for environmental factors.

Now, there is nothing wrong with encouraging people to be accountable, and I think Marxist theories of crime take things too far when they divorce criminality from anything involving personal autonomy; even when choices are very constrained, we see evidence of agency (and to say otherwise is incredibly insulting to the large majority of people from disadvantaged backgrounds who don’t commit crime.) But adults with complex worldviews should be able to account for criminality in a way that does not discount the robust evidence of environmental factors, including poverty, difficult family lives, lead exposure, governmental neglect, lack of educational and vocational opportunities, and understandable, class- and race-based resentments. Unfortunately, this is not how it plays out on parole, where any effort to contextualize one’s personal history prior to the crime of commitment can be interpreted as “minimizing” or “lack of insight.”

This “programspeak” of personal accountability bleeds over to almost all other prison programming. I should know; I volunteered with, and visited, many of them. But it also bleeds out of the prison experience and accompanies people in their lives on the outside. In his ethnographic study of reentry, Alessandro de Giorgi found this self-attribution is so insidious that even after reentry, people blame themselves for not having a roof over their heads or basic groceries to feed their families.

Given the pervasiveness of programspeak, I’m not surprised to find that the folks surveyed by the Marshall Project emphasized their own responsibility. It’s being drilled into them throughout their incarceration. If anything, it’s a miracle that despite this aggressive, programmatic indoctrination, they articulate environmental factors as well. And to the extent that, after everything we know, people still subsribe to this heavyhanded partly-false consciousness, much of it is going to crumble because of the contrast between the consistent pressure on individuals to take responsibility for their actions and the equally consistent reluctance of prison systems to take even a shred of responsibility for what is being done to them, especially in the context of COVID-19.

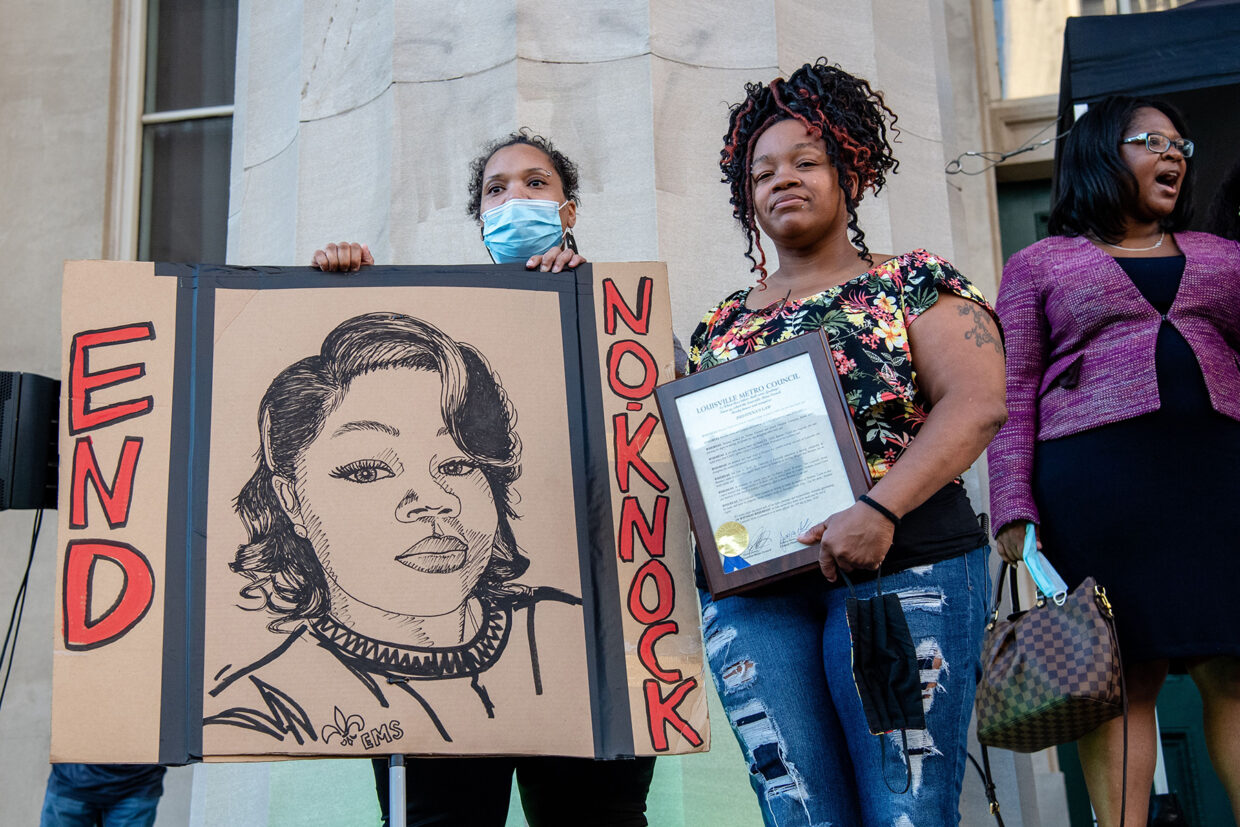

Getting Rid of No-Knock Warrants Isn’t Enough

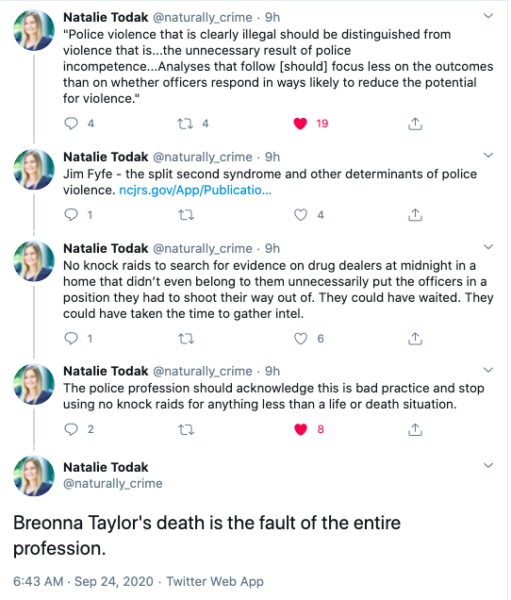

Yesterday we received the news that only one of the police officers involved in the killing of Breonna Taylor was to be indicted–and not for homicide, but for “wanton endangerment” involving shooting toward the neighbors’ homes. Because of the obvious point made by my colleague Frank Zimring in When Police Kill–that the hope to save more lives from police brutality should not be pinned on the criminal process–I want to focus on the question of saving lives, specifically in the context of knock-and-announce. A good starting point is this valuable commentary by my colleague Natalie Todak, who studies policing:

I agree and want to add a few words about how this is not only the fault of police officers, but of the Supreme Court.

You’ve all seen the knock-and-announce rule in action on your TV screens, every time a cop in a police drama loudly yells: “Police! Open up!” What you might not know is that the knock-and-announce rule has ancient roots in common law. In Miller v. United States, officers without a warrant knocked on the door of Miller’s apartment and, upon his inquiry, “Who’s there?” replied in a low voice, “Police.” Miller opened the door, but quickly tried to close it, whereupon the officers broke the door, entered, arrested petitioner and seized marked bills which were later admitted as evidence against Miller in a drug case. The Supreme Court held that “[t]he common-law principle of announcement is embedded in Anglo-American Law” and that Miller’s arrest was unlawful because the police broke in without first giving him notice of their authority and purpose.

The reason for this is obvious. In Wilson v. Arkansas, the court explains: “[A]nnouncement generally would avoid ‘the destruction or breaking of any house … by which great damage and inconvenience might ensue’.” And in Hudson v. Michigan, Justice Scalia expands:

One of [the interests protected by the knock-and-announce requirement] is the protection of human life and limb, because an unannounced entry may provoke violence in supposed self-defense by the surprised resident. Another interest is the protection of property. Breaking a house (as the old cases typically put it) absent an announcement would penalize someone who “ ‘did not know of the process, of which, if he had notice, it is to be presumed that he would obey it … .’ ” The knock-and-announce rule gives individuals “the opportunity to comply with the law and to avoid the destruction of property occasioned by a forcible entry.” And thirdly, the knock-and-announce rule protects those elements of privacy and dignity that can be destroyed by a sudden entrance. It gives residents the “opportunity to prepare themselves for” the entry of the police. “The brief interlude between announcement and entry with a warrant may be the opportunity that an individual has to pull on clothes or get out of bed.” In other words, it assures the opportunity to collect oneself before answering the door.

J. Scalia (Op. Ct.), Hudson v. Michigan (2006)

Granted, in some cases there may be an advantage in hurrying in, because otherwise the police knock on the door can prompt the people inside to destroy evidence–especially in drug cases. But this advantage needs to be weighed against the drawbacks of violence: to mention just two possible scenarios, the police could be making a mistake and trashing the wrong person’s house, or the people inside might mistake them for a rival drug crew and shoot them. Because of these drawbacks, in Richards v. Wisconsin, the Court hesitated to create a special “felony drug exception”, exempting officers from the knock-and-announce rule in all drug cases. They explained:

We recognized in Wilson that the knock and announce requirement could give way “under circumstances presenting a threat of physical violence,” or “where police officers have reason to believe that evidence would likely be destroyed if advance notice were given . It is indisputable that felony drug investigations may frequently involve both of these circumstances. . . But creating exceptions to the knock and announce rule based on the “culture” surrounding a general category of criminal behavior presents at least two serious concerns.

First, the exception contains considerable over generalization. . . not every drug investigation will pose these risks to a substantial degree. For example, a search could be conducted at a time when the only individuals present in a residence have no connection with the drug activity and thus will be unlikely to threaten officers or destroy evidence.

Second. . . the reasons for creating an exception in one category can, relatively easily, be applied to others. . . If a per se exception were allowed for each category of criminal investigation that included a considerable–albeit hypothetical–risk of danger to officers or destruction of evidence, the knock and announce element of the Fourth Amendment’s reasonableness requirement would be meaningless.

J. Stevens (Op. Ct.) Richards v. Wisconsin (1997)

But it’s unclear who the real winner in Richards was. Even though the Court refused to create a blanket exception, the opinion did open the door to special circumstances in which the police might decide not to knock (because of exigent circumstances.) Many of these situations overlap with the exception that the state of Wisconsin sought (and didn’t get.) So we were left with police discretion as to whether to knock and announce or not.

Soon enough, this developed into a practice in which officers anticipated the need to enter without knocking and asked for a carte blanche from the magistrate signing the warrant to do so (so as to cover their asses in case their judgment is questioned at a later date)–and that in itself invited all kinds of shenanigans, such as inventing nonexistent informants to obtain the warrants.

The final blow to the knock-and-announce rule came in Hudson v. Michigan. The main remedy in cases in which the police obtain evidence in violation of the Fourth Amendment is, typically, the suppression of the evidence under the exclusionary rule: the prosecution can’t use it in their case-in-chief. But gradually, the post-Warren courts saw this as a steep price to pay: “the criminal goes free because the constable has blundered.” Because of that, in Hudson, the Court introduced a cost-benefit analysis: The evidence will only be suppressed if the benefit of deterring the police from the undesired behavior exceeds the cost of allowing a guilty defendant to “walk away on a technicality.” Hudson involved a situation in which the police did not knock and announce, and Justice Scalia took the exclusionary rule of the table, arguing that it was not the right fit. While the knock-and announce rule, he said, protected the right of people to be calm and collected when answering the door, it had “never protected. . . one’s interest in preventing the government from seeing or taking evidence described in a warrant. Since the interests that were violated in this case have nothing to do with the seizure of the evidence, the exclusionary rule is inapplicable.” Justice Scalia proceeded to say that the exclusionary rule is no longer necessary:

Another development over the past half-century that deters civil-rights violations is the increasing professionalism of police forces, including a new emphasis on internal police discipline. Even as long ago as 1980 we felt it proper to “assume” that unlawful police behavior would “be dealt with appropriately” by the authorities, but we now have increasing evidence that police forces across the United States take the constitutional rights of citizens seriously. There have been “wide-ranging reforms in the education, training, and supervision of police officers.” Numerous sources are now available to teach officers and their supervisors what is required of them under this Court’s cases, how to respect constitutional guarantees in various situations, and how to craft an effective regime for internal discipline. Failure to teach and enforce constitutional requirements exposes municipalities to financial liability. Moreover, modern police forces are staffed with professionals; it is not credible to assert that internal discipline, which can limit successful careers, will not have a deterrent effect. There is also evidence that the increasing use of various forms of citizen review can enhance police accountability.

This turns out to be untrue. Not only do structural police reforms have mixed outcomes at best, monetary damages are completely meaningless because police officers are indemnified and police departments insured to the hilt. But the real outrage about this decision is the logic that the exclusionary rule has excelled so much in educating police officers about the rights and wrongs of the Fourth Amendment that it’s not necessary anymore. To support this argument, Scalia cited Samuel Walker’s book Taming the System, which showed that the exclusionary rule was an essential component in the reduction of constitutional violations. When Walker heard that Scalia cited his book, he was incensed, and wrote a hilarious-but-irate op-ed in the L.A. Times, titled, “Thanks for Nothing, Nino.” Walker explains:

[Scalila] twisted my main argument to reach a conclusion the exact opposite of what I spelled out in this and other studies.

My argument, based on the historical evidence of the last 40 years, is that the Warren court in the 1960s played a pivotal role in stimulating these reforms. For more than 100 years, police departments had failed to curb misuse of authority by officers on the street while the courts took a hands-off attitude. The Warren court’s interventions (Mapp and Miranda being the most famous) set new standards for lawful conduct, forcing the police to reform and strengthening community demands for curbs on abuse.

Scalia’s opinion suggests that the results I highlighted have sufficiently removed the need for an exclusionary rule to act as a judicial-branch watchdog over the police. I have never said or even suggested such a thing. To the contrary, I have argued that the results reinforce the Supreme Court’s continuing importance in defining constitutional protections for individual rights and requiring the appropriate remedies for violations, including the exclusion of evidence.

The ideal approach is for the court to join the other branches of government in a multipronged mix of remedies for police misconduct: judicially mandated exclusionary rules, legislation to give citizens oversight of police and administrative reforms in training and supervision. No single remedy is sufficient to this very important task. Hudson marks a dangerous step backward in removing a crucial component of that mix.

Samuel Walker, “Thanks for Nothing, Nino,” Los Angeles Times, June 25, 2006

There are now numerous efforts, through litigation and legislation, to outlaw no-knock warrants at the state level. But doing this will not remove the problem. All it will do is forbid the judge from kosherizing the police decision to enter without knocking–a decision that they will still be allowed to make, with no consequences, under Hudson v. Michigan. As long as the Supreme Court does not overturn this decision, the discretion in the field will still be available–and given the post-Warren Courts’ tendency to give officers in the field, making decisions based on “totality of the circumstances”, the benefit of the doubt, the problem will not go away. Not only is Breonna Taylor’s death the fault of the entire policing profession, it is also the fault of the Supreme Court’s lopsided cost-benefit analysis, and I dread to think about the people who will continue to pay the price for these misguided practices.

Blackface Scandals Are the Logical Conclusion of the Performative Goodness Race

As if we don’t have bigger tofu slices to fry–with 57 days till the election, we absolutely do–the academic/activist left is atwitter (pun intended) about yet another blackface scandal. This time, it’s Jessica Krug, African and Latin American history professor at George Washington University, whose identity as “Jess La Bombalera” was, as it turns out, fictitious: she grew up Jewish in Kansas City. Facing imminent unmasking by colleagues who suspected that something was awry, Krug published a self-excoriating screed on Medium, in which she admitted to fabricating “a Blackness that I had no right to claim: first North African Blackness, then US rooted Blackness, then Caribbean rooted Bronx Blackness.”

This mess comes to us just a few years after the exposure of Rachel Dolezal, the NAACP official who cultivated an African-American-passing appearance and sparked a debate on whether “transracial” was a “thing,” and a few months after the death of author H.G. Carrillo (“Hache”) of COVID-19, which exposed his lifelong fabrication of a Cuban-American identity. Because of the nature of the identity-manufacturing–white people posing as black–Krug and Dolezal drew understandable ire, and both scandals erupted amidst waves of uprising about racial inequality.

Plenty of personal trauma and pathology is evident in both stories, but Durkheim taught us to see even the most personal phenomena as social facts. Given the progressive obsession with performance, these scandals are a Petri dish for dissection and, faithful to the trappings of the genre, most of these have revolved around the authenticity (or lack thereof) of apologies. But I found an especially insightful twitter thread by Yarimar Bonilla, who astutely remarks that it was “[k]ind of amazing how white supremacy means [Krug] even thought she was better at being a person of color than we were.” Bonilla offers revealing examples of how expertly Krug trafficked in the tropes of progressive oneupmanship:

She always dressed/acted inappropriately—she’d show up to a 10am scholars’ seminar dressed for a salsa club etc—but was so over the top strident and “woker-than-thou” that I felt like I was trafficking in respectability politics when I cringed at her MINSTREL SHOW. In that sense, she did gaslight us. Not only into thinking she was a WOC but also into thinking we were somehow both politically and intellectually inferior.While claiming to be a child of addicts from the hood, she boasted about speaking numerous languages, reading ancient texts, and mastering disciplinary methods—while questioning the work of real WOC doing transformative interdisciplinary work that she PANNED. She consistently trashed WOC and questioned their scholarship. She even described my colleague Marisa Fuentes as a “slave catcher” in the introduction to her book. Kind of amazing how white supremacy means she even thought she was better at being a person of color than we were.That pathology remains evident in her mea culpa article. Somehow she manages to remain ultra woke and strident, still on her political moral high horse, caling for white scholars to be cancelled –in this instance her own white self.

Yarimar Bonilla on Twitter, Sep. 3, 2020

Bonilla is not the only scholar who blamed white supremacy–in this particular case, Krug’s whiteness–for the scandal: elsewhere on twitter, Sofia Quintero quipped that “[n]othing says white privilege like trying to orchestrate your own cancellation.” But I think there’s something else going on here. As many people have observed, Krug materially benefitted from her deceit, through fellowships and opportunities open to underrepresented people of color. The benefits, however, don’t end there, and it’s time to be honest about this. Overall (no matter how much our Attorney General chooses to ignore this), white people enjoy preferential treatment across the board, starting with the very basic good fortune to avoid humiliating, dangerous, and sometimes lethal encounters with the police, and continuing through intergenerational wealth, opportunity, and representation. However, there are pockets and milieus–and they are not minuscule or insignificant–where being a person of color confers real, valuable social advantages. I happen to know this milieu, the academic-activist pocket, quite well, and I think the social dynamics in it explain a lot. It’s not just scholarships and fellowships (though there are examples of material benefits.) It’s the mantle of authenticity, the uncontested ability to hold a moral high ground, and the sometimes-explicit, sometimes-tacit permission to treat others publicly with disdain.