My advanced criminal procedure course is, as far as I know, the first and only criminal procedure course in the U.S. to include a crimmigration unit. Following a formative semester as a visitor at Harvard, during which I audited Phil Torrey’s terrific crimmigration course, I decided that this was an essential addition–this blog post, which I wrote at the time, explains why.

At the time, I hypothesized that there were knowledge gaps in immigration, which were not completely closed since the Supreme Court’s decision in Padilla v. Kentucky (2010). I was not the only one; in this piece, Gabriel Chin discusses the professional toll that Padilla advising would take on defense attorneys, who would now have to specialize in immigration law. Even in Padilla itself, Elena Kagan–then the U.S. Solicitor General–spoke about her concerns that an entire cadre of professionals would now need to acquire expertise in an adjacent (and not particularly easy to master) field.

True, Padilla did not require defense attorneys to become full-fledged immigration law experts. It only required them to advise clients of the immigration consequences of their conviction if those were clear. The problem is that one needs to know at least something about immigration law to even identify the appropriate statutes (for example, is the person admitted or not admitted to the U.S.? in the former case, the law is in INA §237; in the latter, in INA §212.) You can’t know whether the answer is clear without understanding what the question is, and that in itself requires expertise. A big part of the wisdom, from a defense attorney’s perspective, is having the basic skills to understand whether the immigration determination is even within the attorney’s wheelhouse.

Since Padilla was decided, public and private criminal attorneys have adopted a wide range of approaches to close the knowledge gap. For the purpose of creating my module, I assembled two focus groups of friends from various areas of practice. Beyond two immigration experts (an immigration law prof and a lawyer at an immigration rights nonprofit) I had three prosecutors, one appellate attorney, three public defenders and two defense lawyers in private practice. Before practice-teaching them the modules I created, I asked them where they got their immigration law expertise. I got quite a variety of answers:

One prosecutor said that their office took immigration consequences into account when charging; they had an immigration unit staffed by experts. The other prosecutor said that the D.A. ignored all immigration matters and instructed them to proceed as if immigration consequences did not exist. Out of the defense attorneys, the appellate lawyer was unfamiliar with the field (this is unsurprising, as appellate lawyers would only rarely encounter it.) The bigger, urban public defender offices had immigration units in-house, staffed by experts. In one rural public defender’s office, one person at the office specialized in immigration law and became the office’s unofficial go-to “expert.” In another rural office, everyone learned a little and called immigration nonprofits when they needed advice. The private attorneys were lost at sea and would use published materials from nonprofits when advising their clients. Everyone professed great ignorance and panic at being entrusted with counseling clients on immigration consequences.

The focus groups conversations convinced me that there is great need to add the basics of crimmigration to criminal procedure courses–at least the advanced bail-to-jail courses that are taught to people seriously contemplating criminal justice careers.

What to teach

In shaping the curriculum, I consulted with Phil and with my colleague and friend Tally Kritzman-Amir on what to teach. I decided that the students needed to know what what would touch on their criminal practice (and if they wanted to know more about immigration law, they could take a specialized course.) As criminal attorneys they are most likely to encounter crimmigration when advising clients whether to plead guilty or when negotiating charge bargains, so they would need to be familiar with the most popular removal grounds–aggravated felonies, crimes of moral turpitude, and some of the specific removal grounds–and acquire the skill of ascertaining whether a particular criminal conviction satisfies any of these. Many interesting crimmigration topics, including a detailed history of the immigration code, the immigration removal procedure, detention and bond, and immigration protections, were left out of the curriculum. To facilitate learning, I broke the crimmigration unit into three modules:

Module 1: Background to crimmigration (including Padilla and science-based readings refuting the immigration-crime nexus and examining the emergence of IIRIRA and today’s removal grounds); The admissibility doctrine (distinguishing between admitted/deportable and non-admitted/inadmissible noncitizens, defining “conviction” under immigration law, knowing the consequences of these definitions and distinctions); the categorical and modified-categorical analysis (the basic analytical tool the students would be using in Modules 2 and 3.)

Module 2: Aggravated felonies (explaining what generic offenses are., focusing on the categories of “crime of violence” and “trafficking in a controlled substance”, and highlighting the difference between elements of a generic offense and circumstance-specific elements, such as loss to the victim.)

Module 3: Crimes of moral turpitude (explaining the category within and outside the context of immigration, practicing some cases); the specific grounds of drugs, firearms, and domestic violence

The choice to front-load the mechanics of the categorical analysis reflected the fact that, of all the material I teach in the course, this would be one of the most difficult skills to master, in no small part because the federal removal grounds are so thin, vague, and poorly drafted, and state law can so often be overbroad and abstruse. This was also the reason I chose to sequence the entire crimmigration unit after teaching double jeopardy and sentencing. I reasoned that, at this point in the course, the students would have mastered the art (hopefully taught to them in 1L criminal law) of breaking an offense into its elements. Before teaching double jeopardy, I provided them with a prerecorded refresher on elements of the offense, reminding them that this skill matters beyond substantive criminal law. This way, prior to studying the crimmigration unit, they would practice this skill when determining whether two offenses count as the “same offense” for double jeopardy purposes (under Blockburger) and when determining whether a particular fact must be alleged in the charging document and found by a jury beyond reasonable doubt (under Apprendi.) These two topics would also serve as a rehearsal before learning the categorical analysis and make it more comprehensible.

A note on terminology

The first question I faced was what to call the new unit. I automatically gravitated toward the term “crimmigration”, popularized in Juliet Stumpf’s seminal article. The term has gained considerable traction, becoming the title of César Cuauhtémoc García Hernández’s book and eponymous blog. But then I received a thoughtful note from a colleague who explained that, when Stumpf adapted the term, it was being used in white nationalist/neo-Nazi circles with racist and xenophobic connotations. Its portmanteau construction can also be seen as reinforcing a particular set of suggestions about immigration and criminality that we seek to reject–namely, that there is a nexus between immigration and criminality. My colleague suggested the colloquial alternative “crim-imm”, or the clunkier “convergence between immigration control and crime control” (which reflects, quite well, Stephen Legomsky’s wonderful piece about the asymmetric convergence between the two fields.)

My colleague’s comments were well-taken, and I gave them a lot of thought, but finally decided to keep “crimmigration” as the unit title. There’s value in introducing students to the field by the name the field is known, so that if they seek to know more, it’s accessible and available to them. I also think that terminology isn’t static–it changes over time, and there have been multiple examples of derogatory terms being redeemed and put into empowering use by the people they sought to oppress.

Which brings me to the second issue. Immigration law currently uses the term “alien” to refer to noncitizens (here’s a CIS primer on definitions). Several students emailed, feeling jarred by the statutory terminology, saying it sounded “racist” (I think they meant xenophobic or dehumanizing.) I know this sentiment is shared by many, to the point that the Biden Administration is poised to change the term. I confess that I’m not an enthusiastic convert to the terminology obsession, which does not show any signs of abating. I get it–I’m not stupid–words can create reality. But we’re imbuing words with much more power than they have, I think, and this constant cycle of the linguistic washing machine is diverting attention from more important matters. It reminds me of how, as a child, I heard adults around me say “she has a bad thing… they found something…” treating the word cancer as if it was Voldemort. If a horde of dedicated, progressive-minded Biden officials do a “find + replace” function on the immigration code and replace all instances of “alien” with “noncitizen”, but leave all the removal grounds intact and continue to deny basic Gideon rights to people facing permanent banishment from the country, the enlightened terminology is not going to cheer me up. And given that the zeitgeist is all about certifying only the oppressed for speaking about their own oppression, I am happy to tell you that, prior to my naturalization in 2015, I was an “alien” for fifteen years–an alien student, a nonresident alien with extraordinary abilities, a resident alien–and I always found the term humorous and not dehumanizing at all. If foreigners are dehumanized and marginalized in the United States–and they absolutely are–it’s not because of what the INA calls them; it’s because of what we are misled to think about them. Nationalists were not born with the term “alien” at hand. “Alien” means foreign; it was then borrowed to describe extraterrestrial life. Whatever “they” took, “we” can reclaim, for whatever value of “they” and “we.” In class, I use “noncitizen” when I talk (or, when relevant, “lawful permanent resident” or “visa holder”), and “alien” when I’m quoting legislature, and I leave it at that.

What to read

For this course, I use an electronic casebook hosted by ChartaCourse, which gives me great control ver my materials. I assigned a bit of Legomsky’s article, sections from the INA, and some key cases. The selection of cases presented some challenges, though. The categorical and modified categorical analyses, which are the cornerstone of crimmigration, were established in federal cases, Descamps and Mathis, both of which deal with portions of the Armed Career Criminal Act (ACCA.) This presented a dilemma. On one hand, I wanted the students to know that the categorical analysis will come in handy in a variety of federal legal contexts; on the other, I didn’t want to confuse them and muddle the issue by making them read cases that are not about immigration. I opted for omitting Descamps and assigning only the portion of Mathis that explains the analysis.

As to the rest of the cases, I had to be quite selective and a harsh editor. The cases come from various federal courts and from the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA), and they often involve various issues that pertain to the immigration side of the case, e.g., adjustment of status issues or removal protections. For the limited purpose of criminal practice, the students don’t need to know that. There are also cases that deal with interesting but arcane immigration law sections, and the choice I made was to focus on the common deportation and inadmissibility grounds. I can already see how making the choice to teach these materials will require keeping abreast of the information in a field adjacent to my own with its own precedents, etc., but there are blogs and other good people working on this, and honestly, after Padilla, I do think it’s our responsibility to teach this.

Finally, my materials include one of the best helping tools for criminal lawyers: the ILRC reference table and notes. It is detailed and trustworthy but, as I found, not exhaustive. I’m trying to teach the students not to rely on the table as the be-all, end-all of crimmigration (even though it’s very useful to have on hand) in the same way that I was taught, when I learned statistics, how to calculate F-values and t-values by hand while also learning STATA. There is immense value in doing the exercise by oneself, and I wanted to put people on the path to proficiency.

Crafting problems

Since the second semester of the pandemic, I transitioned my classes to a flipped classroom model: the students receive readings and prerecorded lecturettes in advance. In class, I go over the basics, and the bulk of the time is devoted to solving problems in small groups. Oftentimes, my problems are shaped after real cases. This proved to be a bit tricky in crimmigration. The cases are very complicated and require serious paring down. They are also often BIA cases, which means there are lots of adjacent, ancillary issues to be resolved on the immigration front. This means the hypotheticals need to be carefully edited, and that the ones based on real cases cannot be the first problems that the students solve. I have had to come up with simpler, two-liner problems that the students solve, and then graduate to problems based on recent cases.

Basing the problems on real cases also presented a problem involving the hermeneutics of immigration law. Because removal grounds are so generalized and vague, and because it is difficult to tell, just from looking at a state statute, whether it is divisible or not, there’s an abundance of caselaw, precedent, and courtroom documentation that needs to be looked at to ascertain how to resolve the problem. In the context of a classroom exercise, it is essential that all the information the students need be within the four corners of the problem. So that, too, requires attention in fashioning the problems. And, of course, working through these hypotheticals can be frustrating to the students, because it is ultimately not where the heart of their practice will lie, and it requires them to visit an entire different world of legal meaning-making. Which brings me to the heart of the matter.

The heart of the matter

I think the frustration and incredulity that the students might encounter when studying this material comes from a pretty understandable source: after all, I am essentially teaching them how to twist and turn their main occupation to bypass the perversion that is immigration law. Rather than looking at what a defendant did and charge them with that, they now have to think ten steps ahead, consider what the feds might do, and craft the whole narrative of the case away from the truth if they are trying to avoid immigration consequences.

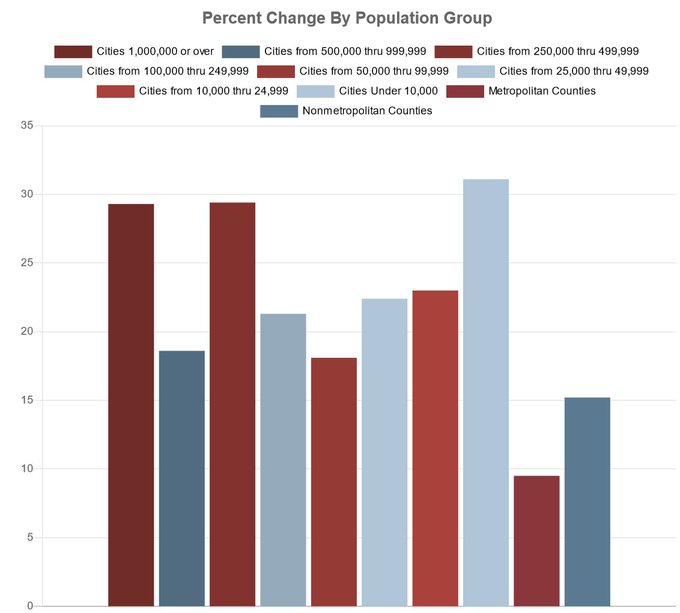

What mitigates this frustration, though, is the other component at the heart of the matter: I kept banging the same drum again and again in class–the fact that, across all places, crime categories, and legal statuses, immigrants commit less crime than the native born. I usually deeply dislike facile, oversimplified slogans, but in this case there’s robust social science supporting that, and I had to talk about that again and again because the perception of an immigration/crime nexus is incredibly pervasive and very resistant to modification–more resistant than any other myth of immigration. I think the students might feel better about learning how to perform this analysis if they know that the purpose is to prevent situations in which ancillary, collateral consequences eclipse the actual criminal process and frustrate its goals.

Stressing the moral imperative to take this so-called externality into account in criminal lawyering is important for another reason. That the categorical analysis is technical and ignores the facts of the cases creates the risk that class will become a glib game, akin to the fantastical hypos that are often part and parcel of teaching 1L criminal law. The somber, urgent quality that accompanies the perceived domestic crises (the prime example is the relationship between police departments and communities of color) can be absent from this unless personal stories of people are brought forth. And the absurdities need to be highlighted for people to feel that what they are doing is not just an intellectual exercise of overlaying one offense on top of the other, but a valuable effort to save families from falling apart.

Striking the right balance

Toward the end of the third module, I asked my students whether learning this material made them more or less confident about their ability to do this. Responses were mixed (even though they knew nothing about this analysis before taking the unit!). I’m not sure that’s a bad result. On one hand, per Padilla, you want the students to feel empowered to offer this kind of advisory to their clients–it is their constitutional duty. On the other, you don’t want them to be overconfident about their ability to clearly predict the immigration consequences of everything under the sun. In this respect, Padilla is too optimistic about the ability of a criminal lawyer to tell a simple crimmigration case from a complex one. Immigration law is ever-changing, very responsive to the blowing of political winds, and what my students are taught about immigration law might not be good law under a new administration. Rather than have them freeze in panic, I would like to empower them to take action: call an immigration lawyer or a nonprofit and consult. Because this isn’t going to be sustainable for every lawyer/client, I think that ultimately the answer to the problem of advising noncitizen clients should be a combination of two factors: the emergence of law school clinics whose job is to offer Padilla support to public and private defense attorneys, and the establishment of an excellent MCLE credit network that keeps criminal lawyers abreast of pertinent developments in immigration law.

If you are a criminal procedure professor who read this, feels inspired, and wants to teach my bail-to-jail course with my immigration materials, contact me (or contact ChartaCourse.)