Yesterday I read an op-ed by Aaron Ciechanover, Chemistry Nobel Laureate for 2004, in which he addresses the growing antisemitic crisis in American universities. Opining about the Harvard/MIT/Penn presidents’ hearing, he has many harsh words for these universities not only as morally compromised, but also as poor places for research to flourish. Unfortunately, the Ha’aretz website does not offer a translation to English, but I’ve translated a relevant part:

A university’s duty is to protect the truth. Nobel Prizes cannot serve as a cover for lying, incitement, and calls to destroy a people and a country. The truth they represent cannot replace the demand for social, historical, and geopolitical truth, for equal morality, and especially for truth, which is a cornerstone of education. Education, not studying. On the difference between the two, which these administrations failed to understand, Einstein said, “education is what remains when we forget all the things we studied in school.”

We must not ignore the problematic aspect of these protests, which radiate to the international scientific collaborations of Israeli academy and, from there, to a negative influence on U.S.-Israel relations. Israel is becoming a cultural pariah. It is essential to use every measure to fight the protests–through Jewish donors and economic institutions led by Jews, or through dialogue with university leadership.

In other words: antisemitism is bad for science. But Ciechanover goes on to hypothesize about Israeli scientists and academics:

By the same token, an opportunity for Israel has opened. Israeli researchers who planned to return during the judicial overhaul sat on their suitcases or tried to look for jobs in the United States. The trend has reversed itself. Many want to come home. Moreover, senior Jewish scientists are looking, today, for a home in Israel–fleeing the rising tide of antisemitism, which hurts them and their children. If positions are found for them in Israeli research universities and in the Israeli tech industry, they will change the course of science and industry in Israel. “Amidst the hardship lives opportunity,” Einstein said. It must be used.

Even though Ciechanover is a gifted, eminent scientist, I have a sense that he is not basing this assumption on data. To be fair, I don’t have any solid data either (though I plan to collect some–I’ll share more as I get to work). I’ve had conversations with dozens of Israeli-American colleagues, many of them with kids, who are deeply distressed and keenly aware of the fact that, antisemitism-wise, things are not looking up for them or their families. I hear of several people in my immediate surroundings who flew home to visit and comfort family and friends and even to volunteer for the reserves or for much-needed agricultural work. But there’s a big difference between that and deciding, or even seriously considering, to permanently return to Israel. There are three main considerations against it, which Ciechanover probably knows all too well:

Personal and family safety. It used to be that the message marketed to diasporic Jews was that their “safe place” was Israel. Who, among those following the news, can still say that with a straight face? Not only has the horrific Oct. 7 massacre shattered any illusions that the government was properly and responsibly protecting its people, but the war is continuing to demand sacrifices (and take a huge toll on human life on both sides) and is anything but safe. Israel is a small country. Everyone I know knows people who have been murdered, raped, kidnapped. Everyone I know has close family members serving in the army. And many Israeli academics have children; the last thing they want for their kids is to be drafted into an irresponsible army, commanded by people their parents do not trust. It’s hard to convey how desperate this dead-end sense feels because public discourse in America has muddled the concept of “feeling unsafe” by equating it with “being upset because someone said something that didn’t sit well with me.” Believe me, Israelis know the difference. Going to work in American universities is supremely shitty these days, I grant you that, and I don’t mean to make light of people’s very real distress that they are losing not only [people they thought were] friends, but entire research networks. I feel the same way and am in the process of a fairly aggressive academic pivot for this very reason: I can no longer breathe the same air with many of the people in my field. But that is a tragedy of the soul, not a serious risk to the flesh, and people will put up with a lot of unpleasantness to provide for their families. Israeli scientists are keenly aware of the gaping chasm between being deeply unhappy at work and being slaughtered by homicidal monsters or sent to fight by a psychopathic career criminal and his trigger-happy messianic government, without a real sense that the people in charge have any idea what they are doing or care about their people. No one wants this for their kids or for themselves.

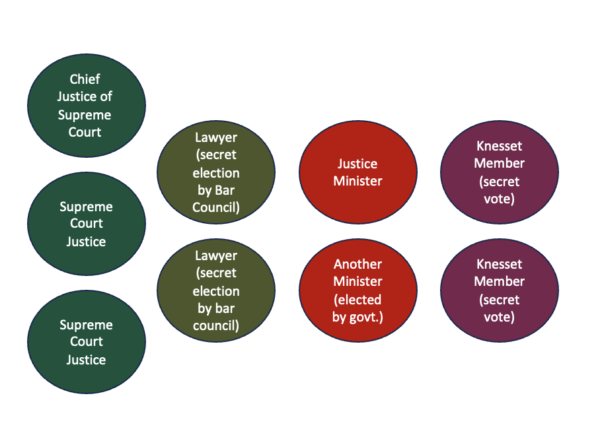

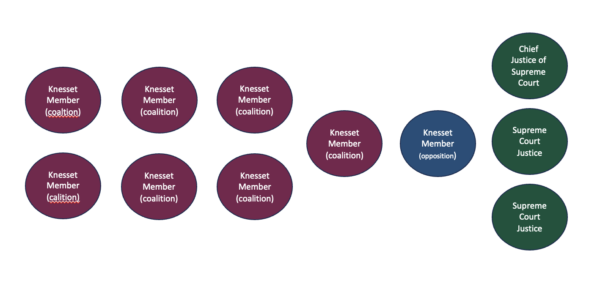

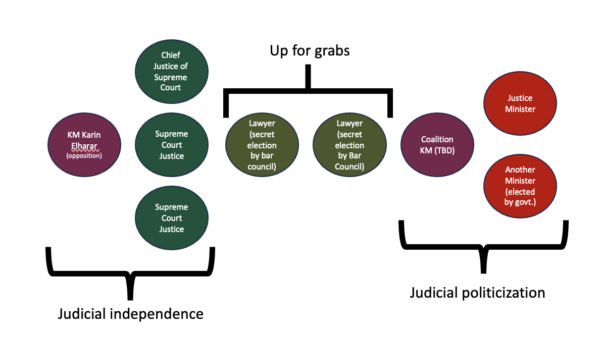

Political problems. This is of course closely related to the deeply worrisome collapse of Israel as a free, democratic country, a long process decades in the making, which intensified in the months before the massacre and the war through the frightening actions of Israel’s 37th government. I’ve written plenty about why hundreds of thousands of Israelis, including my mother and my late father, protested daily in the streets. Academics were a huge part of these protests; in every march I attended there were big contingents wearing t-shirts emblazoned with “without democracy there is no academy.” As one of the most prominent academic protesters, Ciechanover knows this all too well: he was one of the signatories on the Nobel Prize Winners letter against the regime overhaul, warning Netanyahu and his cronies that countries with no separation of powers or freedom of thought end up wrecking their research infrastructure. On one occasion, Ciechanover himself led 50,000 protesters in a march for democracy in Haifa (see image above). Political polls consistently show that academics in Israel were, and still are, among the staunchest resisters to Netanyahu’s agenda. Here in the U.S., academics, scientists, and tech workers are leading UnXeptable, a grassroots movement of expats supporting the Israeli protest movement. Not only have these problems not gone away; many of us see them as the cause for the military and intelligence failures that allowed the massacre to happen, clamor for Netanyahu’s resignation (shameless, despicable man; the buck never stops with him) and are deeply horrified by the atrocities that Ben Gvir’s goons are performing in Gaza and elsewhere, including the appalling murder of Yuval Castleman and a home-grown pogrom at a peaceful village. For many of us, the war has not quelled the spirit of the protest; au contraire, it has intensified its urgency.

Personal growth and prosperity. And all this is related to the fact that, for decades, Israeli governments did very little to encourage promising scientists to remain in the country. My colleagues and I were part of a huge brain drain. Lots of good people who are flourishing, publishing, winning grants and awards, and well respected in their fields, came here after years of subsisting on meager pay as postdocs without prospects in Israeli universities. A disproportionate number of PhDs in many areas, including STEM, means that most people cannot find a job in Israeli universities right away (or ever). University pay, for better or worse, is governed by a collective labor agreement that does not allow universities to pay competitive salaries or match competing offers people receive from universities outside Israel. Back in 2013, the New Yorker ran an explainer story showing that the growing economic distress in Israel–the fruit of Netanyahu’s systematic dismantlement of the welfare state and destruction of the middle class–mean that many people in their thirties and forties (such as academics with young families), in the face of stagnated wages and rising costs of life, were still being financially supported by their parents at an alarming rate. A study conducted in 2007 found that the migration rate of highly educated Israelis to the United States was among the highest of 28 countries examined – more than three times the average. The trend continues: according to this report from i24 News, as of 2022, academics had the highest rate of emigration from Israel at 7.8 percent, followed by physicians at a rate of 6.5 percent. Numerous people I have talked to lately, including folks of serious caliber and international renown, are still looking for the way out.

In other words, I suspect that the growing isolation of Israeli academia and academics abroad is an unmitigated problem, which does not harbor an opportunity to reverse the brain drain. Many of us feel patriotic sentiments, which are bolstered by the ugliness we experience from our surroundings. I don’t mean to belittle that. But we also have a responsibility to our families, and we also understand that living under this government in the aftermath of this horror–if there will ever be an aftermath–is not sustainable. Colleagues working in Europe in the 1930s felt the creeping limitations, followed by expulsions, that we feel; but the alternative they had was to flee to America, whereas our alternative would be to flee–where exactly? One of Ehud Manor’s most beloved songs, written about the War of Attrition (in which my father was injured), is called “I don’t have another country.” For those of us living in diaspora, I don’t feel like we have any country.