Today I received an email from T’ruah, an organization I like quite a bit, inviting me to sign a letter from North American rabbis and cantors. T’ruah’s mission is to “bring[] the Torah’s ideals of human dignity, equality, and justice to life by empowering rabbis and cantors to be moral voices and to lead Jewish communities in advancing democracy and human rights for all people in the United States, Canada, Israel, and the occupied Palestinian territories.” The letter was a call to stop the violence, and it included a denouncement of the murderous Hamas attack as well as a warning about the humanitarian disaster in Gaza. Among other things, the letter said:

Pidyon shevuyim, redeeming captives, is one of the most important mitzvot. Sadly, there is a long history of Jewish communities being forced to practice this mitzvah over the centuries and across continents — from Egypt to Poland to Russia and beyond. We call on Hamas to release the hostages immediately, on Israel to prioritize negotiations for the captives above all else, and on the international community to do everything possible to secure their release.

I agree with this sentiment completely–you’d have to be a psychopath not to–but as I read it, I wondered: Is it really the case that Judaism prioritizes Pidyon shevuyim? Or, more generally, nonviolent negotiation? Do we endorse the important goal of bringing the hostages home because we’re Jewish, or because we are humans with a feeling, crying heart?

Jewish texts usually credit Abraham with the importance of releasing hostages. This shows up in two important texts from this week’s parasha. The first relates Abraham’s fairly peripheral involvement in what perhaps is the first world war in the Old Testament. The parasha describes a violent struggle between a coalition of four kings and a coalition of five kings who rebelled against them. The four kings resisted the rebellion and pursued the rebels, and here’s what happened next:

[The invaders] seized all the wealth of Sodom and Gomorrah and all their provisions, and went their way. They also took Lot, the son of Abram’s brother, and his possessions, and departed; for he had settled in Sodom. A fugitive brought the news to Abram the Hebrew, who was dwelling at the terebinths of Mamre the Amorite, kinsman of Eshkol and Aner, these being Abram’s allies.

When Abram heard that his kinsman’s [household] had been taken captive, he mustered his retainers, born into his household, numbering three hundred and eighteen, and went in pursuit as far as Dan. At night, he and his servants deployed against them and defeated them; and he pursued them as far as Hobah, which is north of Damascus. He brought back all the possessions; he also brought back his kinsman Lot and his possessions, and the women and the rest of the people.

When he returned from defeating Chedorlaomer and the kings with him, the king of Sodom came out to meet him in the Valley of Shaveh, which is the Valley of the King. And King Melchizedek of Salem brought out bread and wine; he was a priest of God Most High. He blessed him, saying, “Blessed be Abram of God Most High, Creator of heaven and earth. And blessed be God Most High, Who has delivered your foes into your hand.” And [Abram] gave him a tenth of everything.

Then the king of Sodom said to Abram, “Give me the persons, and take the possessions for yourself.” But Abram said to the king of Sodom, “I swear to יהוה, God Most High, Creator of heaven and earth: I will not take so much as a thread or a sandal strap of what is yours; you shall not say, ‘It is I who made Abram rich.’ For me, nothing but what my servants have used up; as for the share of the parties who went with me—Aner, Eshkol, and Mamre—let them take their share.”

Genesis 14:11-24.

In other words: Abraham, badass as he was, mounted a courageous military offensive to rescue the hostages, and then declined to partake in the loot.

The second story is also Sodom related. God, appalled by the despicable people of Sodom, determines to ruin the entire city. Abraham gathers the courage to negotiate with him, to ensure that, if there are innocents to be found in Sodom (notably, his own nephew, the aforementioned Lot), he won’t obliterate them–even if there are very few–along with the wicked ones:

And Abraham drew near and he said: Will You also cause to perish the righteous one with the wicked one? Perhaps there are fifty righteous ones in the midst of the city — Will You also cause to perish — and will You not spare the place for the sake of the fifty righteous ones in its midst? It is profane in You to do such a thing, to kill a righteous one with a wicked one, rendering the righteous one like the wicked one. It is profane in You. Will the Judge of all the land not do justice?

And the L-rd said: If I find in Sodom fifty righteous ones in the midst of the city, then I shall spare the entire place for their sake.

And Abraham answered and he said: I have now willed to speak to the L-rd when I should have been dust and ashes. Perhaps there shall lack of the fifty righteous ones, five. Will You destroy the entire city because of the five [and not add Yourself as a “righteous One” to each district to save the whole]? And He said: I shall not destroy if I find there forty-five.

And he ventured to speak more unto Him and he said: Perhaps there will be found there forty. And He said: I shall not do for the sake of the forty.

And he said: Let not the L-rd be wroth and I will speak. Perhaps there will be found there thirty. And He said: I shall not do if I find there thirty.

And he said: Behold, I have willed to speak to the L-rd. Perhaps there will be found there twenty. And He said: I will not destroy for the sake of the twenty.

And he said: Let not the L-rd be wroth and I will speak but this time. Perhaps there will be found there ten. And He said: I will not destroy for the sake of the ten.

Genesis 18: 23-32

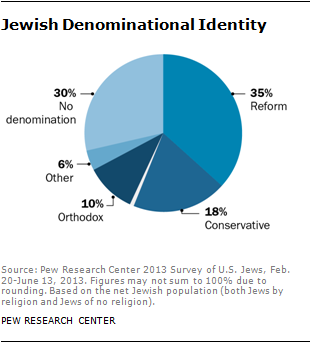

This is often presented as grounding military ethics and, arguably, the edicts of international law, in text. And so, we have T’ruah, and many other progressive Jewish denominations, organizations, and institutions, making a plausible impassioned argument against the impending humanitarian disaster in Gaza, not as an implementation of humanist principles, but as manifestation of Jewish principles.

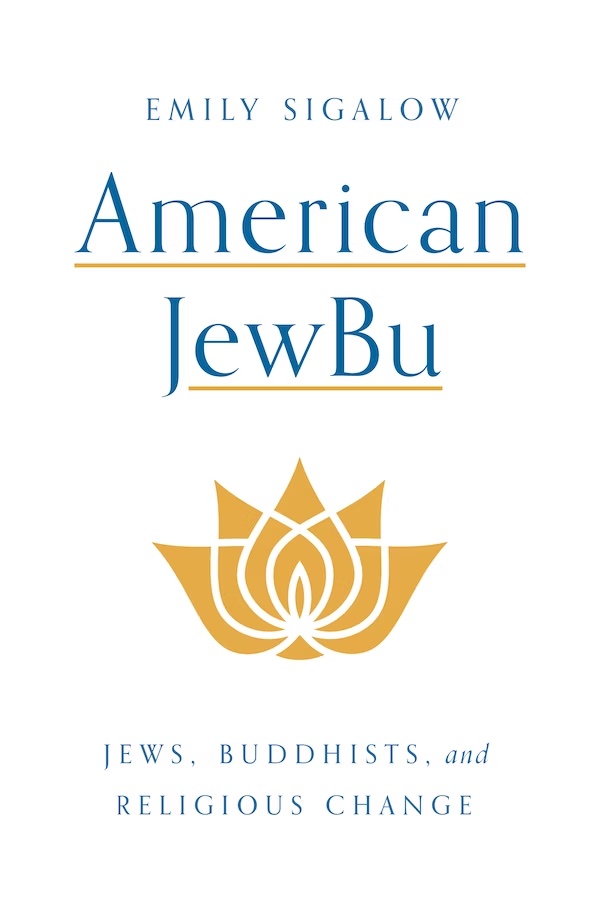

It just so happened that, just as I was thinking about this, I was reading a terrific article by Amod Lele, called “Disengaged Buddhism” (you can find it here.) Lele’s point of departure is the common tendency, throughout various Buddhist denominations, to practice “engaged Buddhism”, i.e., to interpret Buddhism as requiring political activism, most commonly in support of social justice and human rights. An emblematic articulation of this trend is a statement attributed to Thich Nhat Hahn, according to which “Buddhism is already engaged Buddhism. If it is not, it is not Buddhism.” Lele disagrees, both factually and normatively. His article sets out to show that disengaged Buddhism is a coherent, thoughtful position to be found across a variety of at least classical Indian Buddhist texts. But he also makes normative claims: scholarship and advocacy by engaged Buddhists, primarily Western ones, should not ignore these valid sources advocating for disengaged Buddhism, but rather defend their position. He even signals his agreement with an idea that I’ve always found compelling whenever I spent time in Buddhist or mindfulness spaces: namely, that “engaged Buddhism” in the west is less about Buddhism and more about American lefty culture surrounding Buddhism.

I found this last comment incisive and persuasive. Lele critiques Nelson Foster, who argues (either mistakenly or disingenuously, I think) that “the values that have cropped up in the American sangha are

hardly those that prevail in the population of the United States” (52). To this, Lele responds:

American engaged Buddhists’ values may be at odds with those that prevail in Alabama or rural Michigan, but they are not easily distinguished from the values of their non-Buddhist fellows in Berkeley and Vermont and Boulder. Indeed, some of the characteristics Foster attributes to engaged Buddhists are stereotypically so, like “recycling, gardening, and organic farming”. Such values appear far closer to those of their non-Buddhist neighbors than they do to the values in the classical Buddhist texts we have considered.

I think the same story applies to progressive Jewish organizations. Since this horrid tragedy struck, in an effort to process my shock and grief amidst people who are not hostile/antisemitic, I’ve attended services in various synagogues around the Bay Area. What I see, in terms of scripture interpretation, evinces the same maneuver that Lele identifies: the idea that avoiding horrendous war crimes, seeking hostage release as a priority, and caring for the innocent are quintessential Jewish values. Of course I share these values. But are they really the be-all, end-all of what Judaism has to say on the topic? Or can one scour the Old Testament for counterexamples of massive cruelty? Abraham, the righteous protagonist of the two sections from this week’s parasha that I quoted above, was also an absolute monster (by today’s lefty sensibilities) on more than one occasion: his willingness to sacrifice his own son to cement his covenant with God, his despicable banishment of Hagar and Ishmael, his shameless and self-serving pimping of Sarah when availing himself of food available in foreign lands. Not a uniformly commendable character from a progressive standpoint, I think. So, picking and choosing which Abrahamic behaviors are congruent with human rights perspectives when seeking justification in sacred texts is a quintessentially modernist approach to religion, one we find among engaged Buddhists as well as among progressive Jews.

You might say: well, if one wants to prioritize the release of the hostages, what difference does it make if one argues it’s a Jewish position as opposed to a humanist one? Because positing this position as the only possible Jewish position (a-la “this is not who we are”) is factually misleading, the only honest position is that it is a possible Jewish position (this horrendous government is rife with people who, as Jews, are pushing the hostages down the list of priorities and drowning that, and their own incompetence, in abominable rhetoric justifying all the horrors they want our friends and relatives to perpetuate in Gaza. This is not a true-Judaism-versus-false-Judaism scenario. This is a scenario where each side can dig dip into the Jewish bookcase and find plenty of justifications for and against humanitarian action.

It seems like these organizations believe that there is strategic value in staking this position as a Jewish position, because it is held in a debate among Jews, some of them big believers in messianic, aggressive action in Gaza; these folks would undoubtedly find religious argumentation more persuasive than lefty the-occupation-is-evil argumentation. Still, I very much doubt that Ben Gvir et al. are amenable to a good faith conversation about the theological advantages and drawbacks of hostage negotiation. Which is why, I think, there should be no shame–and plenty of integrity–in saying: A position that prioritizes hostage negotiation is a humanist Jewish position, a progressive Jewish position, a peace-and-safety-seeking Jewish position. And that’s a position I would gladly share if I were feeling calm enough or resolute enough to form an opinion. I’m shaken and horrified to my core by the massacre. I tremble and weep at the thought of further horrors: to Gazans, to our soldiers, and above all, to the hostages. I don’t claim any authoritative military expertise on whether peace or negotiation are still viable, nor am I sure that my personal revulsion at violence toward civilian populations necessarily means that one can obliterate Hamas without obliterating Gaza. I hate this whole thing and can’t see anything good coming out of it. And all I want, all I’m ever going to want, is to live to see a news report in which a little boy like mine is returned, alive and unharmed, to his mother’s arms. I can almost see it in my mind’s eye: the running, the crying, the smiles and the applause and the outpouring of love. Pidyon shevuyim. My dream.