The prevalence of Jews among certain American Buddhist communities has provoked lively research and commentary, from Rodger Kamenetz’s classic The Jew in the Lotus to David Bader’s irreverent Zen Judaism which hilariously recounts how “[t]he Buddha’s parents, Max and Helen. . . would describe the miraculous, god-like powers of their ‘little Buddhaleh’” (11-12). Emily Sigalow’s American JewBu: Jews, Buddhists, and Religious Change is an innovative socio-historical and ethnographic contribution to this literature, based on extensive archival work, participant observation, and eighty interviews with Jewish practitioners of Buddhism (all detailed in the book’s superb methodological appendix).

Prior inquiries into the Jewish-Buddhist connection examined the appeal of shared values and ideals (a focus on suffering, text-based theology, attraction to intellectual and bohemian pursuits). By contrast, Sigalow examines the JewBu phenomenon sociologically. Reclaiming the concept of syncretism from its conventional usage (a trifling mix-and-match of religious practices found in traditional societies), Sigalow takes syncretism seriously, showing that interreligious exchange between minority communities is “a process shaped by their specific social locations in society” (8), which has allowed “middle and upper-middle classes (including American Jews). . . [to] appropriate and recontextualize [Buddhism]—and arguably exploit as well as fragment it too—in order to commodify it and place it at the service of their needs” (10-11). American Jews and convert Buddhists, she explains, “share a remarkably similar sociodemographic location in society. . . urban, educated, upper middle class, and liberal. . . thus facilitating the mixing of the two groups” (182). Moreover, Buddhism appeals to Jews as “it [does] not have a legacy of persecuting Jews” (183); and “the flexibility and permissiveness of. . . Buddhist centers enable [Jews] to maintain and preserve their inherited religion, and take from Buddhism the practices and wisdom that support it” (183). This multifaceted appeal of Buddhism to Jews is enhanced through the role Jewish pioneers and teachers played in modernizing Buddhism, and through the wide availability of Buddhist teachers of Jewish heritage.

Sigalow’s book begins with a historical-chronological account of the Jewish-Buddhist encounter. This account begins with the conversion of Charles Strauss, a Jew “brought up the liberal way” (20), to Buddhism on stage at the 1893 World’s Parliament of Religions. The first Buddhist convert on U.S. soil, Strauss practiced and promoted what he considered a pure version of Theravada Buddhism, unadulterated by cultural and ritual trappings and entirely in harmony with science, reason, and social justice. Other prominent Jewish thinkers admired and appreciated Buddhist concepts, downplaying Buddhist cosmology and metaphysics and highlighting their compatibility with science and modernist ethics. While some extolled the romantic interest of Jews in Buddhism, and their fascination with Buddhist public speakers, as a mark of intellectual curiosity, others criticized them for seeking spiritual harbor outside their own faith. Sigalow ascribes Jewish interest in Buddhism in this era to Buddhist modernization in general, as well as to Jewish assimilation in urbane, educated, and bohemian circles, facilitated by the permissiveness and openness of Reform congregations.

This romantic interest in Buddhism, which dwindled somewhat in the early 20th century due to rising anti-Asian sentiments, was replaced by the prominence of solo American Jews trained by Asian teachers who participated in Asian Buddhist groups. In Chapter 2, Sigalow follows three such practitioners. Julius Goldwater was a mystics enthusiast whose family’s relocation to Hawaii led him to Jodo Shinshu and, upon his return to the U.S., to ministry and mentorship at the Nishi Hongwanji Los Angeles Buddhist Temple. During the wartime persecution of Japanese Americans, Goldwater advocated on behalf of the Buddhist community and procured essential supplies for people in internment camps. Samuel Lewis studied Zen with Senzaki and Sokei-An, introduced Senzaki to Sufi leader Pir-O-Murshid Inayat Khan, and pioneered an ecumenical art form, the Dances of Universal Peace, which “set sacred scriptures, poetry, and chants from the world’s spiritual and religious traditions to music and movement” (49). And William Segal, a successful self-made magazine executive, studied the Gurdjeff system of thought alongside Zen, and became a prolific artist and Asian art collector. All three, Sigalow explains, “crafted their own modernized versions of American Buddhism that sought to reconcile it with the central liberal religious perspectives of their time: universalism, perennialism, and romanticism” (45), whether by fostering nonsectarian Buddhism or interfaith dialogue.

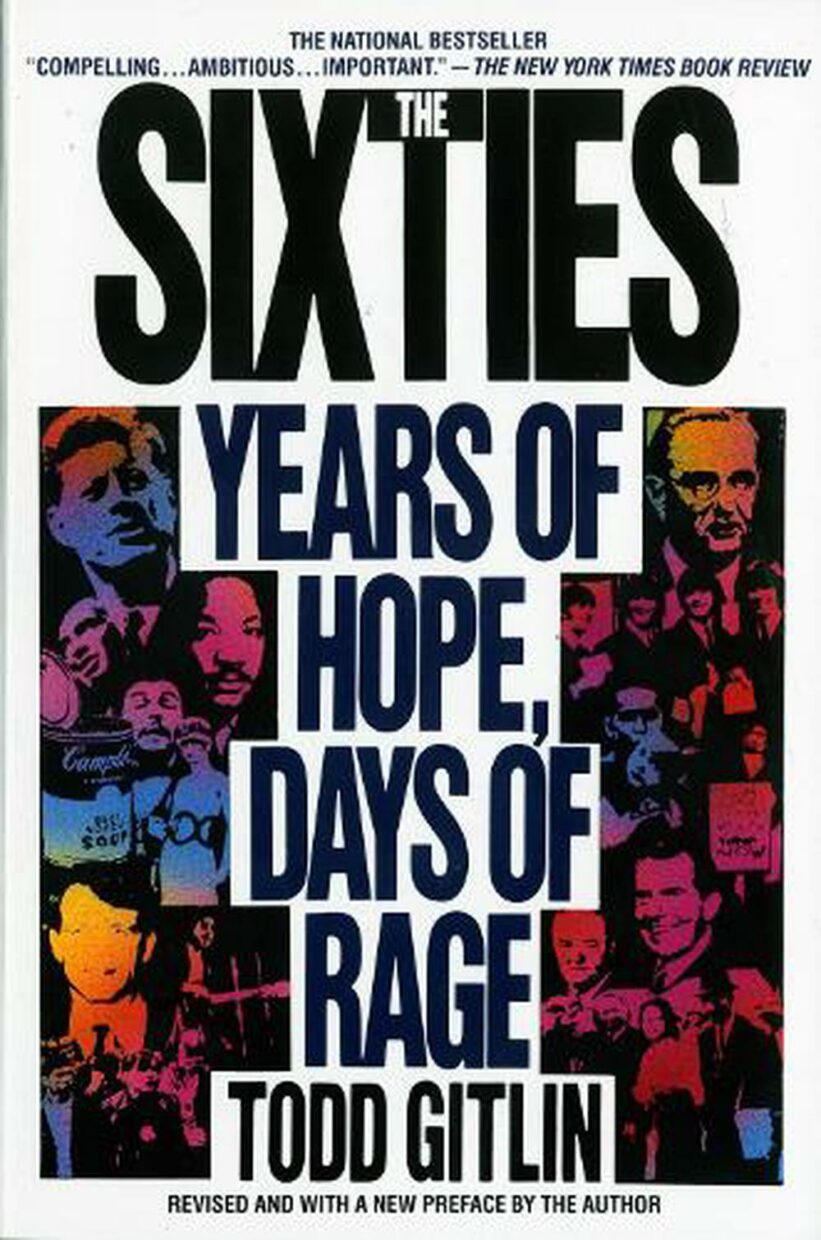

Chapter 3 turns to Jewish participation in countercultural Buddhist practices between the 1960s and the 1990s. Opening with Allen Ginsberg and the Beats’ flocking to Suzuki Zen, Sigalow recounts Mel Weitzman’s leadership of the Berkeley and San Francisco Zen Centers and Blanche Hartmann’s adaptation of Zen Doctrine to the interests and needs of women practitioners. Jewish seekers on pilgrimages to Bodh Gaya encountered Theravada teacher S. M. Goenka, and some of the attendees of his first vipassana retreat– Joseph Goldstein, Sharon Salzberg, Jacqueline Mandell-Schwartz, Wes Nisker, Barry Laping, Stephen Levine, Ram Dass, and Jack Kornfield—established insight meditation traditions in the United States upon their return. Goldstein and Kornfield, extensively trained in Thai and Burmese monasteries, took advantage of the paucity of institutional constraints on U.S. Buddhism, and their innovative teachings “minimized the elements of Buddhism associated with the wider religious tradition of Southeast Asian Theravada Buddhism in favor of the simple practice of seated meditation that they thought would seem less ethnic and more appealing to US society” (64). This period saw the establishment of the Insight Meditation Society in Barre, Massachusetts; Spirit Rock Meditation Center in Woodacre, California; and Naropa University in Boulder, Colorado, established by Chongyam Trungpa Rinpoche. Trungpa’s notable Jewish students included Sam Bercholz, the founder of Shambhala Publications, the foremost publishing house for American Buddhism, and Pema Chodron, author of many books that universalize Buddhist ideas and practices for Westerners. Jewish-Buddhist innovators of this period Westernized Buddhist practices in three important ways: “For one, these teachers elevated the importance of the privatized experience of silence and meditation. Second, they emphasized the ethical pursuit of social justice. And third, they also cast Buddhism with a distinctive psychotherapeutic orientation” (68).

Chapter 4 examines the convergence of Buddhist wisdom seekers with the neo-Hasidic Jewish Renewal movement. It proceeds to discuss the contribution of Jon Kabat-Zinn to the medicalization of mindfulness meditation through MBSR training, and the work of the Nathan Cummings Foundation, an organization “rooted in the Jewish tradition and committed to democratic values and social justice, including fairness, diversity, and community” (86), and its promotion of dialogue between Buddhist leaders, such as the Dalai Lama, and Jewish rabbis and scholars, emphasizing Jewish activism on behalf of the Tibetan people. This chapter—and Part I of the book—closes with the emergence of contemplative traditions and practices within Jewish congregations.

This overview leaves open the question of what, precisely, was distinctly Jewish in these enterprises—or, at least, how the contributions of Jewish liberal intellectuals and scientists differed from those of their non-Jewish counterparts. Much of this history dovetails with more general scholarship on Buddhism and modernity (see here, here, and here, to name just a few examples) and is clearly in line with McMahan’s identification of the three characteristics of Buddhist modernity: detraditionalization, demythologization, and psychologization. Although Sigalow identifies some parallels between the elevation of metta (lovingkindness) and the Jewish tradition of gemilut hasadim, and between the new emphasis on engaged Buddhism and the activist background of many Jewish Buddhist leaders—and although she lists some explicitly syncretic spiritual leaders—she admits that “[i]t is difficult to determine if and how the Jewish upbringings of these Buddhist teachers influenced their decisions to abandon many traditional elements of Buddhism and emphasize the centrality and universality of the practice of meditation” (73).

The second part of the book, however, identifies more salient themes of syncretism. In Chapter 5, Sigalow relies on interviews and participant observations to investigate how meditation teachers diffused contemplative practices into Jewish communities in a way that was “compatible with as well as culturally accessible to liberal American Jewish culture” and at the same time “selected elements from Buddhism that were distinctly Asian” (e.g., no bowing and no Buddha imagery) “and elements from Judaism that were sometimes distinctly Kabbalistic and mystical” (e.g, prayer flags emblazoned with hamsas, language from Jewish prayer as mantra) “so that this new practice of Jewish meditation would feel different, new, and perhaps even exotic or romantic to American Jews” (105-106). The teachers Sigalow interviewed felt empowered to choose elements from Buddhism that they felt benefitted Jews and made them “wiser, kinder, and more compassionate” (117). But beyond these personal factors, the teachers felt that meditation revitalized Jewish communities, and legitimized it by historicizing it within the Jewish contemplative tradition.

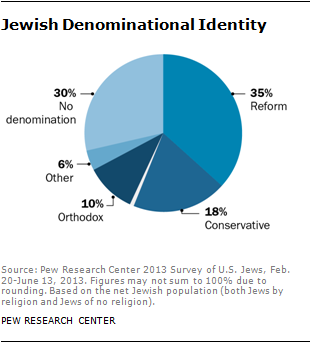

Chapters 6 and 7 turn to Sigalow’s interviews with American JewBus. Few of her interviewees identified equally with both traditions (and embracing a JewBu identity was more evident in younger generations), so Sigalow’s findings mostly address two other groups. The first, the “spiritually enriched”, are observant Jews from liberal denominations, about a third of them holding clergy positions, who consider Buddhist practices beneficial but are not officially affiliated with a Buddhist center. These respondents extol the value of spirituality through meditation practice (a shared aspect of Judaism and convert Buddhism). They speak of spirituality as universal and ecumenical. They seek spirituality that is personally nourishing and connected to their hearts—providing comfort, healing, and relief—and Buddhist mindfulness illuminates those aspects in their Jewish practices. Finally, they emphasize the importance of choosing spirituality voluntarily and intentionally. In these spiritual discourses, Sigalow finds echoes of more general themes in American liberalism.

The second group consists of people committed to organized Buddhist institutions who see themselves as cultural Jews. By contrast to traditional scholarship about converts eschewing their former identities, the interviewees retain their Jewish identity and perceive it as innate, through family- and heritage-based connections, connected to the history of the Jewish people and to the experience of being non-Christians in a Christian-majority country; their Buddhist worldview and practices, by contrast, are “an achieved identity” (159): deliberative, reflective, and “welcome[ing] and cultivat[ing] the liberal values with which they were raised” (164).

Sigalow’s reflection on these findings reflects remarkable nuance on the themes of power and privilege. While Jews did not intend to exploit Buddhism, she explains, “their distancing of Buddhism from its Asian cultural systems and ethnic identities—and recasting it in a socially active and psychotherapeutic framework—effectively ‘whitened’ it in order to make it more appealing to a broad American audience. . . a quintessential tactic of colonization” (190). Moreover, “[t]he construction of Jewish meditation thus began with a radical secularization of Buddhism and ended with a resacralization in Jewish forms. One could argue that this was a Jewish appropriation of the cornerstone practice of the Buddhist tradition” (189). Nevertheless, Sigalow observes, syncretism is “an inevitable outcome of sustained religious contact. Religions continually remake themselves in response to changing historical as well as social conditions and interaction with other traditions, adopting elements from each other that enhance their durability, and shedding those that no longer remain compelling or resonant. This process of religious reconfiguration allows religions to survive and carry forward into the future, remaining relevant to future generations” (190).

Within this conversation lies what I think is missing from Sigalow’s sociological analysis: Jews’ marginalized position precisely within the privileged, educated, white, lefty social locus they occupy. Antisemitism is alive and well, and in the context of the progressive milieus that are the socio-political home of many JewBus, it is inextricably linked to strident political critiques of Israel, which tend to lack the nuance these milieus reserve for other “isms”. This can make life in the intellectual left uncomfortable and burdensome for Jews—considerably more burdensome than coping with questions of cultural appropriation for Buddhist converts. This makes the JewBu experience quintessentially American and raises the question of a possible comparison with Jewish-Buddhist syncretism in Israel, where Buddhism seekers, sympathizers, and adopters’ relationship with their faith of birth might be complicated by an Orthodox, rigid, and exclusionary relationship with the state apparatus, rather than with a contested minority status. This Israeli American JewBu would like to read (or write) a comparative piece along those lines someday.

This minor quibble aside, Sigalow’s book paves a fresh empirical path for scholarship on the Jewish-Buddhist encounter. Her survey instrument reflects deep understanding of, and empathy for, her subjects’ spiritual identities and practices; her participant observation reports ring authentic and perceptive. Her conclusions are a valuable reminder that no spiritual, religious, or ethnic community is a monolith, and that religions and customs change and evolve, diverge and converge. These lessons will gain even more importance as the next generation of JewBus—perhaps the children of Jewish-Buddhist families—turn to shape their own identities and create their own meanings.