Just as I’m preparing to fly out and receive the American Society of Criminology’s Hindelang Book Award for FESTER, I stumble across the book page for Behind Ancient Bars on UC Press! Behind Ancient Bars is also available to preorder from Amazon. No Kindle version yet, though that’s sure to follow. The book officially comes out on May 12, 2025.

Fighting Bigoted Work Environments: Tips from the Trenches

It’s been a few weeks since I started providing pro bono legal services to professors and students confronted with antisemitic bigotries at their universities and colleges, and a few months since I started providing ersatz advice to people emailing me about their campuses. What I’ve seen so far is a paraphrase of Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina opening: each unhappy academic situation is unhappy in its own special way. The experience at a gigantic R1 university in the Midwest might be different than the experience at a tiny college town on the East Coast, and the experience of STEM researchers might be different than one of people in the arts and humanities. I’m already at a place where I can see some similarities, though, and it’s time to offer a few things to consider.

What Is Your End Goal? Any person wants to feel safe, welcome, and valued at their workplace. Unfortunately, a big part of this desired outcome cannot be obtained through legal measures. It might be useful, as an exercise, to ask yourself what concrete things about your campus experience you would like to see improve. For example, were talks and events on campus violently disrupted? One thing to do would be to reinvite the speakers and compensate student groups for losses incurred at these events. Were violent incidents left uninvestigated? You might want them to be looked at more seriously. Are there any areas of campus that are barricaded or otherwise impermeable to students and faculty? You can ask for free passage throughout campus. Are people being compensated, in terms of promotion and advancement, for espousing views that are congruent with those of the violent protestors, or penalized for expressing dissenting opinions? Perhaps the faculty handbook needs updating about promotion standards. These are all concrete things that can improve campus climate. By contrast to this stuff, as I’ve said to several people, expecting symbolic groveling from the administration or insincere apologies from individuals who do not feel apologetic at all is a losing premise that creates rancor and does nothing for you in the real world. Some remedies are debatable: I know folks who have more faith than me in the premise of including antisemitism literacy, or viewpoint diversity issues, in the campus DEI package. Only you know whether, on your campus, this would be meaningless pageantry or a pathway to lasting change.

One Big Incident versus Lots of Little Ones. If you’ve been blatantly discriminated against in a provable way, this one incident could be all you need for litigation. But in a lot of the cases I see, people go through weeks in which nothing that happens around them is beyond the pale, and everything complies with the broad understanding of First Amendment principles. You could walk through a gauntlet of horrid flyers and booths, see advertisements for events in which lies and incitement to hate will be proclaimed, get the stink-eye from people who used to be your colleagues or even friends, spy some ugly social media content from people you sometimes get coffee with at conferences, and get a couple of meanspirited student evals. Any of these things on its own might not brighten your day–might even blemish it–but grownups know that adult professional lives are not a bed of roses and Mama said there’d be days like this. Whether or not in the aggregate we’ve hit the mark of an abusive work environment is a big question, and the answers could depend on the disposition and worldview of the individual judge. Which brings us to the question: How ardently do you want to fight this?

Fighting a Legal Battle Has Pros and Cons. If you’re facing some sort of disciplinary procedure, like a Title XI complaint or something similar, you really have no recourse but to fight back with everything you’ve got. But if you’re the one initiating the escalation, such as if you want to start building a Title VII case based on your work environment, you have to make a choice: how much are you willing to take, psychologically and practically, to obtain evidence for your case? I’ve now heard of cases in which people were so harangued and mistreated at faculty meetings that they stopped showing up. Attending a meeting where you are derided and berated can be the source of a lot of misery and isolation, and it’s understandable that not everyone has the stomach to withstand prolonged exposure to abuse. But you cannot trust a record of a meeting you have not attended in person, certainly not if the meeting hasn’t been recorded or transcribed. Bigoted remarks and slurs will likely not find their way to the record, and if you haven’t heard them with your own ears, they are not always provable. Relying on second-hand rumors is also risky in the sense that the people who experienced the event might be paraphrasing, or exaggerating, or telling you their interpretation rather than the naked facts. Moreover, even the best employment or civil rights lawyer cannot do this for you. They don’t know your campus, they don’t understand the relationships and the people involved, the long histories of campus issues will not make as much sense to them as they do to you. Also, in my experience, many lawyers are unfamiliar with the highs and lows of academic careers, and thus might not understand that there’s a whole banquet of consequences ranging from “nothing” to “being fired,” and that, as an academic, you could be paid a full salary and still be treated like a leper on campus. All of which is to say: if you want documentation, you have to commit to collecting it yourself, and that calls for fortitude and tolerance that not everyone has 100% of the time. You are the best judge as to whether the benefit is worth the psychological cost.

What Is and Is Not a Bigoted Remark. Bigotries and hatreds tend to be expressed in broad, vague brush strokes, and sometimes rely on words that can have a derogatory cultural resonance for some people but sound completely innocuous to others. This is true of many hatreds on the basis of race, gender, national origin, ethnicity, religion, you name it, and it is especially true of antisemitism which, kind of like a virus, tends to mutate and express itself differently across time and place. If one is a researcher in the social sciences or humanities, and has studied the intricacies of dogwhistle utterances and their cultural underbellies, one would read a lot of offense and derision into the use of certain words, but might be surprised that lawyers and judges who do not share these linguistic sensitivities are not in a hurry to adopt this understanding. E.g., oblique references to greed, friends in high places, crassness, etc., which might ring in your ears as antisemitic, might not read the same way to people without your attention to hermeneutics and familiarity with the history of antisemitism. In these cases, careful documentation of the context surrounding the utterance might be useful.

Keeping Solid Records. If you want to fight this fight, make it a habit to write down detailed memos, as accurately as you can, shortly after the events or conversations take place. I’m a fairly experienced ethnographer, and I’ve learned from years of fieldwork that, even if you think to yourself, “I’ll never forget what this interviewee said,” you will, unless you record it immediately. If some comment or encounter has shaken you up, sit at a café or at your office or at home and write down the facts: who said what.

Ask for Clarifications. Unclear as to why something has happened to you? Rather than stew in your own interpretations, ask as straightforwardly as possible. If you’re getting some poor review, or bad news about a promotion, ask what the criteria were. Use neutral language: “I would like to know where I fell short, so that I can be more competitive at this [x thing] in the future.” Accusing people of bigotry in these scenarios rarely goes over well, and risks that they will clam up, denying you invaluable information you can accurately record, compare to the academic regs, and invoke next time it comes around. When confronted with vague accusations about conduct in class, a-la “we felt unsafe,” it is especially important to ask dry, informative questions to figure out what the facts were.

Facts Are Not Opinions. Opinions Are Not Facts. If a colleague or student claims that you said X or did Y and you did not, their claim is false. But if they say that you are an idiot, or that they dislike you, they do have a right to their opinion, even if it’s an ugly, bigoted opinion (as an aside: attacking people for having an unfavorable opinion of you, or asking for intervention from the administration, casts you in the role of a petulant child and is unlikely to produce tangible improvement.) The problem with subjective opinions begins when people in power assume that they are objective referenda on a person for raises, promotions, etc. In other words, if an administrator denies you promotion on the basis of murmurs from people who dislike you, rather than on the basis of your proven record of scholarship, pedagogy, and service, that’s when we do have a legal problem.

Did Nothing Wrong? Do Not Apologize. Something I’ve now seen a few times is an instructor confronted with some vague accusation made by anonymous students and asked for a comment. If you’ve done nothing wrong and have nothing to apologize for, say: “I have done nothing wrong and have nothing to apologize for.” Rehearse this if you need to – it is a basic act of self-preservation. Non-apology apologies, or insincere or incomplete apologies, are more likely to be twisted against you and misused in proceedings. Not apologizing when you are innocent also preserves your own sanity, because in the face of outlandish accusations, even people with a solid moral fiber and strong character can begin to doubt the facts (I see a parallel of this in the world of false accusations and confessions in criminal cases.) Of course, if you *did* do something wrong, the buck stops with you, and you should apologize and do better in the future.

Stay Lawful with Recording. One way to keep accurate records of conversations about advancement and work conditions is to surreptitiously record them on your phone, but depending on where you live or work, that might be illegal. In many states, recording a conversation requires the consent of both parties, and if you surreptitiously record, you are committing a misdemeanor. Find out whether your state has an all-party consent law here and keep to the limitations of the law. Needless to say, do not ever lie, falsify, forge, use creative AI, or whatever, to present evidence that is not true.

At the Same Time, Assume Others Are Recording. At my home institution, the default is that every classroom is audio recorded, and we have signs alerting our campus population to this fact. Some people bristle about this and talk about academic freedom and stifling surveillance, but I think it’s excellent policy. To paraphrase James Comey: Lordy, I’m glad there are tapes! If you have a similar rule and find yourself accused based on a surreptitious recording a student made in class, you now have some control over whether the recording was edited or manipulated to twist the narrative. Most institutions do not record as a matter of course, but I recommend that everyone in higher education behave as if they did. In other words: Assume that everything you say outside of your own home, and within earshot of anyone who is not a member of your immediate family, is being said in public. If whoever heard you is quoting you faithfully and you truly are at fault for something, the buck stops with you. If they twist it, lie about it, or choose to interpret it in vile ways, the buck stops with them, and you should fight them every inch of the way.

Lateral Moves: Pros and Cons. Some folks are pretty exasperated with the administration and environment where they are and looking for a lateral move, which is understandable. If you have a sense that there are no responsible adults around you who understand the difference between free speech and terror and who protect you from discrimination and abuse, look for a place that seems healthier in that regard. But consider that, especially if you’ve been somewhere for a considerable period of time, you’ve earned respect that will be difficult to replicate at a new place, and institutional reactions to, say, a swastika or a trashed mezuzah on your office door might vary based on how much personal cache you’ve accrued at your workplace. If you do decide that your workplace is not salvageable, please exercise due diligence about any prospective workplace. Ask the people who work there, honestly and sincerely, whether they feel comfortable and welcome on campus. Look up bigotry incidents online and get a sense of whether there are isolated incidents (no university is perfect) or part of a pattern. Also, consider what effect your staying or going might have on a spouse who is also employed at the university, or on your kids.

Consider Whether You Want to Buy Into the Victim Game. There are two main paradigms through which one can see experiences of discrimination and abuse: looking for recognition of oppression and victimization, and looking for pride and celebration of one’s identity. There is a lot in the college environment that pressures in the direction of the former, and I suggest balancing it out with the latter. Extend kindnesses to students while also encouraging them to be proactive and resilient about the situation. Respectfully and patiently argue with people who lack good information or profess to know things they don’t. One of the most powerful examples of this approach is the wonderful Holocaust museum in Skokie, which I recently visited. After the town residents, many of whom were Holocaust survivors, lost their Supreme Court case against the Nazi march, they realized that they, too, have freedom of speech, and inaugurated an educational enterprise like none other. The museum includes an amazing exhibit in which the audience can directly interact with holocaust survivors who were recorded and made into holograms, and hear their life story from their own mouths. At the end of the experience, there are pictures of the survivors who narrate the museum exhibits, and the words, “I did not tell you this to weaken you, but to strengthen you.”

Come Together. Are you the only person who is being mistreated, or do you have colleagues that experience the same thing? Rather than isolating yourselves, come together and talk about this. If there are several of you in the department, take turns attending meetings and taking notes. If there’s a university Hillel or other affinity group or institution that could be helpful, liaise with them. In some places, there’s a regional Hillel office that serves several institutions, and you can reach out and make friends at other institutions (which is always a bonus.) Additionally, a pattern of discrimination that targets people of the same racial, ethnic, and/or religious group, reduces the odds that mistreatment will be dismissed as a consequence of one particular, oversensitive personality. It also offers the benefit of celebrating your heritage and culture with others, which is so important when times are tough. And, talking through this stuff with other people can help you collectively figure out what you want to get out of this and whether legal action is the way to get there.

Welcome Home: The Value of a Human Life

The wonderful videos are up and tears are rolling down my cheeks: children hugging their parents, families hugging grandparents. Hostages are being returned. I wished for nothing more than to live to see these videos and my heart flows with gratitude. I have been watching Ohad Munder’s first hug with his dad again and again, sobbing with joy. But I feel so much inquietude around all this, mostly paralyzing fear for the fate of the remaining hostages. And I fear that some of this dark teatime of the soul has to do with confronting the transactional value of human life.

Recently, I got to read a classic anthropological text from 1923 by Marcel Mauss called The Gift. Mauss marshals evidence from various societies in which gift-giving is common to show that gifts are not spontaneous or selfless; rather, they are surrounded by elaborate social norms that dictate how to give, how to receive, and how to reciprocate. Gifts are an important and thoroughly ritualized social adhesive. At no time is the issue of reciprocity and value-setting clearer than when witnessing a hostage exchange, which makes a transaction out of the gift of human life between parties whose animosity is at its peak. As I read coverage about the Israeli hostages and the released Palestinian prisoners I think, who is being valued more? Whose children are coded as “children” and who are coded as “prisoners,” “Palestinian terrorists,” or “Zionist occupiers”?

The transactional nature of the releases brings into stark relief the range of values that the many stakeholders and parties to this conflict affix to different human lives. A few years ago, I read Peter Singer’s The Most Good You Can Do, where he makes an impassioned argument against parochialism. By contrast to Rashi’s adage that “the poor people of your own town come first,” Singer argues that all lives have the same value and that altruistic giving should therefore eschew parochial considerations and, instead, maximize the good for as many people as possible. I understand, cognitively, what Singer is trying to say, and of course I cognitively comprehend that every life is precious. But I think that, in his admonitions, Singer is being less than responsive to the basic workings of human psychology, which I am observing in my own soul as well as in the souls around me.

A Gazan family will be welcoming a released teenager soon with their own joy, adjacent to the Israeli joy but not touching it. The folks online reminding and admonishing and lecturing about how you can feel for both sides are able to host a modicum of generalized warmth because they are not psychologically invested and wound up in one side of this conflict or in another. This is not about who has a heart and who is heartless, but about where people are positioned. And I’m beginning to think that Rashi did not issue an edict so much as offered a description of where people’s natural sympathies flow.

(As an aside, it is such a psychologically bizarre experience to scroll through Facebook posts, finding Israeli and, to a lesser degree, Jewish posters concerned with the fate of the hostages and posting incessantly about them and about the war, while other people post silly memes and their Thanksgiving tables. The folks who post thus are not bad or evil or lacking in empathy. It’s just… not their thing. How many horrific human disasters in faraway lands have I heard about and, while feeling keen sorrow for those involved, moved on with my life, largely unaffected?)

Along these lines: twenty-four people were released yesterday, 11 of which were Thai and Nepalese workers. What a heartache, to be thrusted into the heart of hell in a conflict unrelated to you, because you had to move away to a far away land to make a living; to find yourself caged and tortured, caught between parties in a war zone. Initially, their names and pictures were unavailable, anonymous in captivity and in liberty as they were when trying to make a living in a cruel global economy. This morning I finally saw their picture. I was so moved to see Jimmy Pacheco’s release and how he was embraced by kibbutz members. The man for whom Jimmy worked as a caregiver, Amitai Ben-Zvi, was murdered by Hamas, and Jimmy was kidnapped and manhandled with horrific violence. The world devalues the lives of foreign workers so systematically and deeply. The hug between Jimmy and members of the Ben-Zvi family was a balm to my heart.

And then there are the lists. A huge, painful, never-healing wound in Jewish history involves the Judenrat’s listmaking in ghettos, making horrifying decisions on who must be saved and who must be shipped to the east to be murdered in concentration camps. It is really hard to reckon with the fact that people’s demographics play a horrifying role in setting their price in hostage exchanges. I wake up nightly from horrible nightmares involving the toddlers in captivity, especially baby Kfir Bibas, and shudder when I consider that the monsters who hold them captive understand the psychological value we affix to children. As my beloved late colleague Sherry Colb and her husband, Michael Dorf, wrote in Beating Hearts, there is a special premium on the lives of children.

And at the same time, there is a frailty to aging people (which I addressed in several of my works). And I’m so moved by the return of the brave, stoic grandmothers, many of whom lost husbands to sadistic murderers. But this also means that the precious lives of young men are going to be devalued by comparison, and that they will have to withstand captivity longer, and I worry that the calculus of the worth of human lives versus military objectives will change as the war rages on.

Speaking of Colb and Dorf’s book, I also think a lot about the lives of animals brought into this homo sapiens conflict. One brief clip from the horror footage of October 7 keeps sawing through my mind: the murderers and kidnappers drive a truck away with hostages on it, weeping. The family dog chases the truck, barking, running, trying to save his family members. And these evil monsters shoot the dog dead. Why? WHY?! Why the dog? What does the dog have to do with any of this? Is the dog a Zionist occupier? I think about all the families who had to make the tough decisions to leave their dogs and cats outside their safe rooms and shelters. Family members whom they loved and cherished, like we love and cherish Inti and Gulu. What a thing to confront and to reckon with. They were trying to save their children’s lives, their parents’ lives. What choices people have had to make. And what complicated feelings to process amidst the layers of horror and grief.

I’m sure I’m not the only person who is confronting complicated and uneasy feelings about all this. What makes me feel a bit better, a bit more inspired, is an amazing statement made by Yoni Asher, whose wife and two daughters were returned from captivity yesterday. Asher says: “It is okay to rejoice and it is okay to shed a tear, but I am not celebrating and will not celebrate until the last of the hostages returns.”

May we live to welcome them all home.

An All-Male Jury for a Groper and the G2i Problem

The Gemara relates: Rav bar Sherevya had a trial pending before Rav Pappa. Rav Pappa seated him and also seated his litigant counterpart, who was an am ha’aretz (a simple man, not a rabbi). An agent of the court came and kicked and stood the am ha’aretz on his feet to show deference to the Torah scholars there, and Rav Pappa did not say to him: Sit. The Gemara asks: How did Rav Pappa act in that manner by not instructing the am ha’aretz to sit again? But aren’t the claims of the am ha’aretz suppressed by Rav Pappa’s perceived preferential treatment of Rav bar Sherevya? The Gemara responds: Rav Pappa said to himself that the litigant will not perceive bias, as he says: The judge seated me; it is the agent of the court who is displeased with me and compelled me to stand.

Shevuot 30b

Understandable outrage is brewing among many folks around me: At a San Francisco trial of a man accused of stalking and groping women, all the jurors are male. How could this happen? And is it lawful? Let’s go over some terminology:

- Population: everyone who lives in the county.

- Sampling frame: the group of people from which one can draw a sample. For our purposes, the folks whom the law deems eligible to serve on juries in the county.

- Venire: Everyone who received summons to appear for jury selection (the selection process itself is called “voir dire.”)

- Panel: The people who are eventually seated on a particular jury.

The constitution requires that the jury be drawn from a “fair cross-section” of the population: in other words, that the jury pool–the overall sampling frame from which people are summoned for the venire–be reflective of the population. If some recognizable minority group is systematically disqualified from serving, the selection method is unconstitutional. In the landmark case Taylor v. Louisiana, the Supreme Court invalidated a jury selection scheme by which women were not summoned at all to the jury pool unless they explicitly chose to opt in. Similarly, schemes like Texas’ “key man” system, where there’s some official who gets to pick and choose who’s on the jury (and thus, for example, underrepresents Mexican-Americans) have been invalidated.

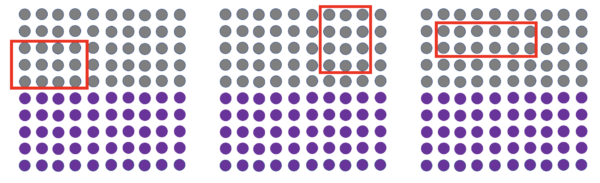

Having a sufficiently diverse jury pool, however, does not guarantee the empaneling of a diverse jury. Consider the following example: you have 100 pebbles, 50 of which are gray and 50 of which are purple.

The statistical odds of drawing a purple pebble are 0.5, which means that, in a random selection of 12 pebbles, the stats predict you have great odds of having a mix of gray and purple pebbles. But you can easily imagine many random drawings that will only include gray pebbles.

This is exactly what happened here, except for an important fact: the twelve jury members were not drawn at random. Annie Vainshtein and Nora Mishanec reported for the Chron:

During jury selection, some women said they could not impartially weigh the evidence that would be presented at trial due to personal experiences with sexual assault or harassment, or negative feelings toward Hobbs’ attorney, which prompted Superior Court Judge Harry Dorfman to dismiss them.

Others from the pool were unable to serve on the jury for different reasons; one woman said she had booked an upcoming cruise. Several jurors, one of whom was male, were dismissed after expressing opinions including that “sexual predators” should be segregated from society, and even face the death penalty.

By the end of jury selection, the only woman selected was an alternate juror, who will hear all of the evidence but vote on the verdict only if needed.

Here’s the thing: robust social science research tells us that, when looking at groups of people in the aggregate, people’s life experiences and worldviews, which are often a function of their demographics, impact how they will assess evidence and judge a case. Which is why, even without resorting to the services of expensive trial consultants, prosecutors assume that people of color will be favorable to the defense, and defense attorneys assume that white men will be more punitive. The name of the game in voir dire then becomes getting rid of as many people whom you suspect will be unfavorable to your side. The problem is that, even though we can make these generalizations regarding groups, we have a deep social distaste about making them regarding individuals: people generally recoil from being told that they must think a certain way because of who they are, even though in the aggregate we know such statements to be true. This is why one can’t mount a for-cause challenge for disqualifying a woman, any woman, from the trial of an alleged stalker/groper just on the basis of her sex/gender. In science, it’s known as the group-to-individual (G2i) problem, and it affects various areas of legal decisionmaking.

Over the years, parties have tried to skirt this problem by using peremptory challenges to get rid of demographics they suspected of being unfavorable to them; the advantage of this strategy was that peremptories didn’t require an explanation. But the Batson doctrine allows the opposite party to challenge such use of peremptory challenges when they reveal a pattern of discrimination against a suspect racial or gendered group. It used to be the case that all the prosecution had to do was provide a race neutral explanation for their challenges (which, admittedly, would be difficult if there was evidence to refute this.) Now, California’s new peremptory challenge laws, enacted through AB 3070, make it a lot more difficult to get away with this sort of thing, because the prosecution’s explanation has to be reasonable, and it also cannot correlate with a seemingly race-neutral explanation that strongly correlates with race, gender, or any other suspect category.

But this is not what happened here! The women were dismissed using for-cause challenges because they directly opined that they would not be able to impartially weigh the evidence. This I find dubious (though not impossible) and it leaves me with serious discomfort. To drive home the problem, consider the following analogy: assume a white police officer is on trial for shooting and killing an unarmed black man. Imagine that, at jury selection, every single black prospective juror says that they would not be able to impartially weigh the evidence and, consequently, we end up with an all-white jury. Does this pass the “fair cross section” test? Yes–there were people of various races in the jury pool. Does this pass the Batson test? Sure! No peremptory challenges were used; everyone who was struck was struck for cause. Are you comfortable with the outcome?

How could this have been fixed? First, I think that prospective jurors can and should trust their ability to make good decisions with the life experience that they have. Like 50% of the people on the planet, I have been sexually harassed, catcalled, groped, pestered for sex, and other fine experiences. Does that mean I would not be able to seriously consider the possibility that a person who did this to others was severely mentally ill, or that there was an eyewitness identification problem? I worry that the emphasis we put on group identity in contemporary discourse has locked people into beliefs that they are immutable members of whatever demographic they belong to and there’s nothing more to them, and that is impoverishing and disappointing. Second, I think the onus here was on the prosecution to ask the prospective jurors questions that would probe the extent of the bias. For example, I think a fair question would have been, “would your experience with harassment lead you to find someone guilty even if there was defense evidence that the police got the wrong person, or even if there was persuasive psychiatric evidence that the defendant didn’t know what he was doing?”

If such a stunning number of women find themselves unable to fairly adjudicate a sexual harassment case, then the root of the problem here is not the jury selection process itself. It is the fact that harassment experiences in public space are so common and far more malignant than people think. In her book License to Harass, my colleague Laura Beth Nielsen exposes the unbearable lightness of offensive speech in public space and the many insidious ways in which it affects people’s everyday lives and decisions. It turns out that even behaviors that might not be a big deal on a one-off basis can add up to the point that people are so fed up with them that they don’t feel they can be objective on a jury.

If that’s what happened here, it’s a damn shame. Because the irony is that the very fact that there are many other people like this guy (who maybe just yell obscenities, rather than grope, and thus completely escape public censure) is what makes it impossible to adjudicate this guy by a true jury of his peers, which should include women.

#SmithfieldTrial: The Most Absurd Miscarriage of Justice You’ve Never Heard Of

St. George Utah

The first thing you notice upon waking up in Saint George, Utah, is the breathtaking, majestic beauty of the mountains. The striking nearby towering rocks, a bright red against the blue sky, are echoed in the grandeur of the far away mountains in shades of gray and blue. Let your gaze drop a bit and you’ll contrast this dramatic natural scenery with the ugly sprawl of an extensive strip mall, festooned with motels, cheap restaurants, and highways. But much of the town is a celebration of beauty, starting with its most visible landmark. Established by Mormons who fled Vermont and then Illinois, the town was divided into lots, which were raffled between the pioneer cotton-growing families. Brigham Young, whose winter residence is open for public touring, dreamed up the big temple, which gleams in its colossal whiteness, along with its steeple, in the middle of town. Elder Edwards, who leads the tour, tells us that Young was unhappy with the original, shorter steeple; After his death, lightning struck the offending steeple, which persuaded the townspeople that Young was speaking to them from the next world, and they built one of more impressive stature.

The town nowadays is a mix of Mormon heritage, a faith still practiced by much of the population and ever-present in landmarks and street names; college professors and students from Utah Tech and Dixie University, among other institutions; artists, who are responsible for the many works of public art decorating the town’s many squares and traffic circles; and endurance athletes running and cycling along the mountainous trails. There is a phenomenal independent bookstore, an old-fashioned barbershop, a historical theatre showing international horror films, and a vegan restaurant, Gaia’s Garden Café, which whips up delicious rice bowls and exquisite matcha lattes.

In the center of town stands the Fifth District Courthouse, where my friends, Wayne Hsiung and Paul Picklesimer, stood trial this week for burglary and theft. The facts? Wayne and Paul, along with two others who pleaded out, entered a pig factory farm in Beaver County, Utah, operated by Smithfield Foods, and rescued two dying piglets, Lily and Lizzie.

Smithfield

Smithfield, a major supplier of pig meat to Whole Foods, Costco, and other large retailers, claims to raise the pigs “humanely”, but the truth is very different. The footage obtained by Wayne, Paul, Andrew, and Jon shows what actually happens inside the facility (which is now owned by a Chinese company).

The two piglets the activists removed from the facility, Lily and Lizzie, were nearly dying, suffering from a variety of ailments. Importantly, Smithfield had falsely declared that it ceased its use of gestation crates (confinement cages for mother pigs that do not leave them any room to move), and the investigation exposed that these were still in use.

Smithfield was extremely invested in its good name, which allowed it to market its pig meat as “humanely raised.” Exposing the truth would have adverse consequences for the company. And so began an investigation by the FBI, which would not only involve spending my tax money and yours on an extensive hunt for the piglets by a “six-car armada of FBI agents in bulletproof vests”, but also hurting the pigs and traumatizing sanctuary employees. Glenn Greenwald, who covered the story for the Intercept, wrote:

The attachments to the search warrants specified that the FBI agents could take “DNA samples (blood, hair follicles or ear clippings) to be seized from swine with the following characteristics: I. Pink/white coloring; II. Docked tails; III. Approximately 5 to 9 months in age; IV. Any swine with a hole in right ear.”

The FBI agents searched the premises of both shelters. They demanded DNA samples of two piglets they said were named Lucy and Ethel, in order to determine whether they were the two ailing piglets who had been rescued weeks earlier from Smithfield.

A representative of Luvin Arms, who insisted on anonymity due to fear of the pending criminal investigation, described the events. The FBI agents ordered staff and volunteers to stay away from the animals and then approached the piglets. To obtain the DNA samples, the state veterinarians accompanying the FBI used a snare to pressurize the piglet’s snout, thus immobilizing her in pain and fear, and then cut off close to two inches of the piglet’s ear.

The piglet’s pain was so severe, and her screams so piercing, that the sanctuary’s staff members screamed and cried. Even the FBI agents were so sufficiently disturbed by the resulting trauma, that they directed the veterinarians not to subject the second piglet to the procedure. The sanctuary representative recounted that the piglet who had part of her ear removed spent weeks depressed and scared, barely moving or eating, and still has not fully recovered. The FBI “receipt” given to the sanctuaries shows they took DNA samples “from swine.”

Several volunteers at one of the raided animal shelters said they were followed back to their homes by FBI agents, who dramatically questioned them in front of family members and neighbors. And there is even reason to believe that the bureau has been surveilling the activists’ private communications regarding the rescue of this piglet duo.

Value of the pigs

Lest this suggest that the pigs were of immense value to Smithfield, between 15 and 20 percent of the piglets, who grow up sickly and starved in the factory conditions, are exterminated. And sometimes, this mass extermination take the form of mass suffocation, as another DxE investigation revealed in 2020. Matt Johnson, who uncovered this horrifying practice, was charged with a violation of Iowa’s ag-gag laws, but the charges against him were dropped. It’s worth reading Marina Bolotnikova’s Current Affairs story about Matt’s legal exploits.

Paul and Wayne were not so lucky, and the trial against them, with charges for agricultural burglary and theft, proceeded, animated by the interest of Utah’s state attorney, who receives campaign donations from Smithfield. On Wednesday night, I flew to Las Vegas and drove two hours into St. George, ready to testify on Wayne’s behalf.

I was not there as an expert witness, but rather as a character witness: I know, like, and respect Wayne, have collaborated with him on lawful campaigns such as the fur ban in San Francisco (which was successful and later expanded throughout California), have spoken on his podcast, and have invited him to my classroom to show the footage and speak with my students (many of whom considered his visit the highlight of the entire course.) Coming up with a witness list and crafting the legal arguments was complicated. Judge Wilcox, who presided over the trial, severely limited what would and would not be admitted. In a series of blog posts, and in a book chapter, I explained that the natural legal framework in open rescue cases was the necessity defense: a justification for breaking the law in order to prevent a worse evil from occurring where no legal options to prevent it exist. But arguing necessity would open the door to ample proof of this “worse evil”, including showing the footage of Smithfield’s barbaric practices, and that Judge Wilcox did not want to allow. So, Wayne and Paul would rely on other defenses: claim of right, lack of mens rea (no “intent to commit a felony within”), and a lack of value of the “property” in question. They would show the footage to illustrate that the piglets were worthless to Smithfield. Even so, Wayne, Paul, Paul’s Utah attorney Mary Corporon, and the small team of dedicated law students who supported them with research, would face a ferocious uphill battle in their efforts to introduce relevant evidence in the face of Judge Wilcox’s determination that this was “a burglary case” and he would not tolerate it becoming a political soapbox.

Because I gave testimony only on Friday, I was banned from watching the trial footage in advance. I say “trial footage” because Judge Wilcox, who described the activists as “criminals” and “vigilantes” severely curtailed access to the trial. The activists, many of whom flew or drove hundreds of miles to support the defendants, would not be allowed in the courtroom. Judge Wilcox allowed only five people in the court at the time, anonymized the jury and, at some point on Thursday, cut off the WebEx streaming of the case, launching into an angry tirade against “vigilantes” (there is no evidence of intimidation or, really, anything that was not peaceful, 100% legitimate protest). Moreover, the legal team, who operated from a nearby AirBnB, saw strangers in suits skulking around the bushes surrounding the property and removing their trash, and when they came out to speak to them, the strangers fled in a black van, saying something into a worn microphone, and falsely claimed to be the “owners” of the AirBnB. At least one side of the trial was determined to uphold due process, and I didn’t want to mingle with the activists who were watching the trial, so I spent hours on Thursday hiking the mountain ridge and visiting Pioneer Park, Red Cliffs Desert Garden, and several city landmarks, like the temple and Brigham Young’s home. I got to talk to a lot of kind and pleasant city residents, many of whom knew that the trial was taking place there (it landed there through a change of venue from Beaver County, where half the jury pool would be comprised of Smithfield employees.) Throughout it all, I wondered why this trial evoked such panic or, more accurately, why the panic was so painfully misdirected at those who exposed the horrific cruelty rather than those who perpetuated it.

The answer I came up with, which I later saw play out again and again throughout the trial, was this: There is nothing more threatening to a human being than raising even the remote possibility that one is not a good person. People will go to incredible lengths of self deception, cognitive contortion, and actions in the world, to avoid confronting even the remotest possibility of a blemish on the goodness that is such an inexorable part of their self identity. This is true for all those who consume Smithfield’s products, or, really, any other animal products, and try to avoid any footage that might show them that they are complicit in something horrible. This is also true for all those who protect these abominable secrets–law enforcement agents, prosecutors, judges–who so desperately want to cling to the belief that they are the good guys and on the right side of this that they flout due process, the constitutional public trial clause, the jury trial rights, and pretty much any other constitutional protection the defense has.

The panicked blockade of transparency was evident throughout the trial (as I’m now piecing together from what I saw with my own eyes, my conversations with the legal team and the journalists, and the WebEx footage and twitter stream I followed after I got off the stand.) During voir dire, one prospective juror said he knew what jury nullification (the power of the jury to decide a case according to their moral convictions, rather than the law and the evidence) was. The judge struck him, saying that he wanted to “save a peremptory challenge for the prosecution.” This strikes me as outrageous, even against the backdrop of hostility to nullification in criminal courts. Judges admonish juries that they must decide the case according to the law and the evidence, and, as explained in this useful and well-written piece by Jordan Paul, “deliberately conceal [nullification power] by scrubbing references to nullification from the entire process.” In United States v. Kleinman, a Ninth Circuit case, the Court held that a jury instruction “severely admonishing” against nullification was unconstitutional, but that the resulting error was harmless. But the fact that nullification exists and is lawful is a matter of general knowledge, so it seems that Judge Wilcox overstepped the constitutional line here.

It would not be the last time. The most ferocious battles in court were fought over the extent to which the very limited allowable defense scope (what with necessity and, subsequently, claim of right off the table) required showing the jury footage from Smithfield. The entire field of evidence law deals with the balance between admitting evidence with probative value and suppressing evidence that is prejudicial. The kicker, of course, is that what makes a good piece of evidence probative is also what makes it prejudicial–namely, that it evokes a strong response. This kind of strong response might suggest that there is something awry at Smithfield and, by extension, that consuming their pork was not a good thing to do, so Judge Wilcox would not allow it. Many of the films were censored and limited to still images. In a more reasonable decision, the judge cut off the sound of the video, to exclude Wayne’s narration of what he was seeing inside the facility. but with the effect of silencing the agonized screams of the pigs. Nevertheless, some footage would have to be allowed, because of its direct import to the questions of mens rea and value. To commit agricultural burglary in Utah, one must have a specific intent to remove property: Wayne and Paul argued that their intent was to document conditions on the ground, and that the removal of the pigs was for the purpose of saving them. As to value, Wayne and Paul argued that the pigs, deathly ill from deprivation, a foot injury, and an inability to nurse, were of no value to Smithfield, undermining the definition of “property” in Utah’s theft statute.

Some of the ensuing battles over evidence are described in this informative KSL piece by Emily Ashcraft:

The jury trial for Hsiung and Picklesimer stretched throughout the week, and was filled with objections from the attorneys in an attempt to keep the trial within the parameters set by the judge. Mary Corporon, who represents Picklesimer, and Hsiung, representing himself, would argue that certain steps taken by the state should allow them to bring in more information about the farm conditions, including showing the video.

Janise Macanas and Von Christiansen, Beaver County attorneys, objected when a witness started talking about other conditions, specifically about a dumpster on the farm with dead piglets inside or the mother pig’s health.

Testimony was offered by veterinarians chosen by both sides, an investigator, a Smithfield employee and a man who was part of the same undercover operation of the farm in 2017.

After all of the testimony in the case had been offered, the judge issued a directed verdict dismissing the first count against both Picklesimer and Hsiung. Corporon argued that each of the burglary counts was specific to a building, and that the two defendants did not expect to see piglets in a gestation barn — meaning they would not have been entering the barn with an intent to steal.

There was also a discussion about a possible mistrial. Hsiung and Corporon argued that the prosecution asking a state veterinarian about care for the pigs at the farm opened the door for them to bring in new evidence about the conditions of the farm. The prosecutor said that was simply an effort to show that the two specific piglets would have had a chance of receiving medical care that next day.

The judge said bringing in that much new evidence at the end of the day on the last day of trial was not an option.

“I’m not going to open up testimony again in this case, and if we need a mistrial, we’ll have one,” Wilcox said.

Ultimately, Corporon and Hsiung decided to continue with the trial, after the state’s attorneys agreed with asking the jury to not take into account that testimony.

On Thursday, Hsiung called himself to the witness stand, asking himself questions and then opening himself up to questions from the other attorneys. While questioning himself, he admitted to taking the piglets, but said it was not theft because he took piglets that were of no value to Smithfield.

Hsiung said the case is not about burglary and theft but about animal cruelty and animal rescue. The two piglets were given names after they were taken from the facility, Lilly and Lizzie, and he spoke about their conditions.

Although he said they did not intend to take piglets, during his testimony he admitted they had a veterinarian on hand in case they brought out animals and that they had evidence that there were animals dying on the farm. Hsiung said they had taken animals in the past during similar operations, sometimes with the owner’s permission.

He argued that he had a belief that the piglets were abandoned property, and prompted witnesses to testify that the piglets were more of a liability to Smithfield and he may have been helping them by removing the piglets from the property. Ultimately, though, he said the purpose was to save the piglets from “certain death.”

“We were not there to be burglars or thieves,” Hsiung told the jury. “We were there just to give aid to dying animals.”

I witnessed the judge’s wrestling with the factory farm content firsthand. Under direct examination, I spoke about how Wayne and I met and about some of the animal rights advocacy we had done together. When asked to give examples of Wayne’s honesty and integrity, I started explaining how open rescue works–that open rescuers keep their faces revealed and their identities known and take responsibility for what they’ve done even when it means facing scary consequences. Just as I started speaking, Janise Macanas objected, the judge (who seems to have been a bit taken aback by fancy professors siding with the defendants) put the kibosh on the rest of my testimony, and that was that.

Here’s what I would have said, if I were allowed to speak: Wayne’s honesty and integrity are obvious to anyone who meets him. His willingness not only to face incarceration in Utah, but possibly to lose his license to practice law in California (a previous attempt to disbar him for saving animals failed), is admirable. Every social movement that tries to improve the world must encompass lots of different people: the food engineers and companies that bring us Beyond Burgers, the chefs and bloggers who bring us wonderful vegan recipes, the mainstream advocacy groups that seek legal change, the law clinics and nonprofits, and yes, the people who are willing, at great expense and sacrifice, to actually risk going into these horrendous facilities and tell us how our food is being made. These folks provide an invaluable service to the movement, which should embrace them rather than distancing itself from them. It’s crystal clear who the good guys and who the bad guys are in this case. And intelligent, curious people should be very suspicious when someone is trying to keep important information from them.

The mistrial issue was quite heartwrenching to experience. Dr. Sherstin Rosenberg, the veterinarian at Happy Hen sanctuary, testified about the condition of the piglets, discussing their inability to nurse and their injuries. Not content with this, the prosecution put Dr. Dean Taylor, the state veterinarian, on the stand as a rebuttal witness. But it turned out, during Dr. Taylor’s evidence, that Smithfield employed a grand total of two veterinarians for more than a million pigs. Later rebuttal testimony from a Smithfield employee, which confirmed this, led to a flood of questions from the jury about the medical condition of pigs at Smithfield (to the point that I wondered how many of the jurors would eschew pork, or become vegan altogether, after this trial). Judge Wilcox was visibly despaired by all this. He had tried so hard to rein in the trial and avoid discussing the real issues, but, despite his best efforts, the animal cruelty stuff slipped from under him and occupied front and center at the trial. In desperation, he proposed holding a mistrial. I thought this would be a fantastic end to the whole thing. My hope (perhaps misguided?) was that the state of Utah would realize that they should stop throwing good taxpayer money after bad, and refrain from reprosecuting–particularly in Paul’s case. I also hoped (perhaps against hope?) that, after declaring a mistrial, Judge Wilcox would pick up the phone, call the state attorney, and tell him that reprosecution was not worth it. But Wayne and Paul decided to proceed forward with the trial. The unsatisfying compromise was that Judge Wilcox instructed the jury to ignore the rebuttal testimony from the veterinarian and the Smithfield employee.

What happened at closing arguments is aptly described in the KSL article:

On Friday evening, Christiansen claimed Hsiung admitted to taking the animal, but attempted to minimize his crime with contradictory testimony. He said Hsiung testified that he didn’t intend to take a pig, but in the script of the video shared at trial, Hsiung said, “If we see an animal we can take out, we’ll take them out.”

He talked about how Hsuing and the rest of the group went into the facility on March 6 and March 7, but did not take any animals on March 6. Christiansen said this shows they were not just taking piglets that needed emergency care but were taking pigs as part of a publicity move.

“The pigs were just props in a video, props in a movie,” Christiansen said.

He said the animals were alive and did have value, and any evidence of poor health displayed at trial is speculation.

Christiansen also talked about the charges for Picklesimer, and said holding the camera was a very important role in the burglary, allowing Direct Action Everywhere to produce a video and raise donations.

“Every person that participated in the burglary that night was part of the crime,” the prosecutor said.

Picklesimer’s attorney, however, said he did not even touch a pig, and did not intend to commit a theft and should not be held accountable for something he didn’t do.

She told the jury if they do believe Picklesimer might be guilty based on being part of the group, the should directly consider the worth of the piglets to Smithfield.

“Bottom line these piglets are worth nothing, it’s a net negative,” Corporon said.

She said what Picklesimer did was like standing next to someone else who was emptying a trash can.

Hsiung presented his arguments last, making a plea to the jury to consider their feelings and recognize a difference between stealing an animal and helping an animal.

“We did not intend to take a piglet out who had anything of value for Smithfield,” Hsiung said, arguing that these two piglets did not have any commercial value.

He told the jury he did not want to be acquitted based on a technicality, but hoped they would make a ruling that would make a difference to animal rights.

“If you defend our right to give aid to dying animals, defend the right of all citizens to aid dying and sick and injured animals, there’s somethings that will happen in this world. Companies will be a little more compassionate to the creatures under their stewardship. Governments will be a little more open to animal cruelty complaints. And maybe, just maybe, a baby pig like Lilly won’t have to starve to death on the floor of a factory farm,” Hsiung said.

He argued that theft and burglary are not the right way to charge him in this case, and suggested different steps should be taken to address actions like this, including companies and governments listening to their suggestions or charges for trespassing.

I’m now back at home, processing what I saw and heard at the trial, as the jury in St. George is deliberating the verdict. I very much hope that the little exposure they received to the horrendous evil that is factory farming will persuade them of the negligible value this “property” has for its “owners”. I only wish they could see the piglets now. One member of the legal team, who lives in Colorado, gets to visit with the pigs once ever few weeks, and reports that they are lovely and doing very well. I also hope Wayne and Paul made the right call. We had some conversations about whether going with the mistrial was “good for the movement” or not; both parties made numerous mistakes, as is inevitable in the course of a complicated trial, and those would not be repeated in the second trial. But a well educated, curious jury is also something that is difficult to give up. Having done my very small part in this case, I’m keeping my fingers crossed for the right outcome. If you want more coverage, following @SmithfieldTrial on twitter, as well as journalist Marina Bolotnikova and activist Jeremy Beckham, will be useful, or use the hashtag #SmithfieldTrial.

On the Administration of Tough Love

This spring brought in its wings a mountain of work: in addition to my full-time Hastings position, I guest-taught across the bridge at my alma mater, UC Berkeley. I accepted the overload job for various reasons, financial and others, but in addition to the academic joys of being near many old friends (and especially my beloved and admired mentor) and resuming old professional conversations that I enjoy, there were immense athletic joys: every day I was there, after class and office hours, I would revisit my old stomping (splashing?) grounds and swim a good workout on campus. With my favorite facility, Hearst Pool, closed, I sometimes swam in the gorgeous Golden Bear pool, surrounded by a forest and almost always empty, but most of the time I swam at Spieker Pool, the enormous Olympic-sized facility that is home to Cal’s celebrated swimming and diving teams. Oftentimes over the years, when I swam there, the Cal women’s team would be training in adjacent lanes; I was starstruck by all the fantastic athletes I cheered during Olympic games and world championships and concluded that, if I was managing one lap to every two of Missy Franklin’s, then I was not too shabby.

Like many Bay Area swimmers, I had enormous respect for Cal’s legendary champion, Natalie Coughlin; I read her biography, Golden Girl, which highlighted her special working relationship with coach Teri McKeever. Both women rose to prominence on parallel tracks: Natalie earning medal after Olympic medal, Teri becoming the first woman to coach at an Olympic level. In the book, Teri is presented as a thoughtful, considerate coach, who treats Natalie like the adult that she is, by comparison to Natalie’s prior coach at the Terrapins team. Teri is also presented as sensitive to the needs of the teammates as whole young women, often counseling them on personal and interpersonal problems.

Which is why it came as quite a shock to read in the Mercury News and in the OC Register an exposé revealing serious allegations of bullying and abuse against McKeever from several swimmers:

[I]n interviews with SCNG, 19 current and former Cal swimmers, six parents, and a former member of the Golden Bears men’s team portray McKeever as a bully who for decades has allegedly verbally and emotionally abused, swore at and threatened swimmers on an almost daily basis, pressured athletes to compete or train while injured or dealing with chronic illnesses or eating disorders, even accusing some women of lying about their conditions despite being provided medical records by them.

The interviews, as well as emails, letters, university documents, recordings of conversations between McKeever and swimmers, and journal entries, reveal an environment where swimmers from Olympians, World Championships participants and All-Americans to non-scholarship athletes are consumed with avoiding McKeever’s alleged wrath. This preoccupation has led to panic attacks, anxiety, sleepless nights, depression, self-doubt, suicidal thoughts and planning, and in some cases self harm.

Following the publication of the allegations, as the Mercury News reports this morning, Berkeley swimmers walked out on McKeever on this morning’s practice.

I found myself extremely upset at learning all this; it comes in the heels of Mary Cain’s exposé of running coach Alberto Salazar’s abuse (she thoughtfully reflects on her time training with the Nike team in this great episode of the Rich Roll podcast and in this NY Times video.) We are all still collectively reeling from the sexual abuse that Simone Biles and others suffered at the hands of Larry Nassar, and from the neglect–no, dereliction of duty–on the part of their coaches and sports association to offer them any help. These latest scandals brought home the understanding that U.S. coaches and mentors were perpetrating the same horrors as the infamous Romanian and Russian coaches. Which, as someone who teaches and mentors people at these age brackets (young adults), makes me wonder – what is the meaning, or the purpose, or the appropriate concoction, of tough love?

It’s hardly disputable that the current generation of young students/trainees/athletes have a strong culture of bringing into the light things that previous generations believed should be suffered in silence. I found this interesting article about the attributes of Gen Zers as students instructive and useful. This trait, of not tolerating abuse/indignity, has both lights and shadows. At its worst, it creates a grievance mentality that encourages people to marinate in their traumas and difficulties without fostering the resilience they need (and that previous generations seemed to possess to a greater degree) to overcome them. But at its best, it makes some of us older folks question whether we should have spoken up, rather than remain silent when we suffered similar or worse harm at the hands of the people who were supposed to teach or mentor us.

As I write this, I vividly remember a whole litany of small and medium-sized cruelties that were inflicted on me during my youth and adolescence, starting with my school’s ignorance/inaction at the sadistic and systematic bullying experiences I went through between the ages of 9 and 14, continuing with the terrifying and inhospitable (albeit publicly admired and celebrated) professors and intellectuals who taught us in law school, and then with the gallery of commanders and trainers who used us, in the army, as their psychological punching bags. If anything, I marvel at the fact that the 1980s and 1990s, when all this happened to me and around me, were years in which we gradually developed sensitivity to sexual harassment, while ignoring all other forms of harassment that were still happening, unopposed, in plain sight. We regarded all that stuff as rites of passage and fodder for our hindsight comedy about the hazing we received. The thing to do, our boomer parents taught us on the rare occasion that we revealed our unhappiness to them, was to laugh it off and develop tougher skins. And I can’t say that this advice was completely misguided: later in life, when a staff member at Hastings raised her voice at me about some administrative matter or other, I calmly replied, “Girlfriend, I have been yelled at by people much scarier than you, so I propose you lower your voice and think twice about opening your mouth again.” For me, the experience of suffering was also a gateway toward empathy and compassion: I have never been incarcerated, isolated, or on death row, and I’ve never been assaulted in prison or neglected medically, but I sure as hell know what it’s like to be lonely, hated, disbelieved, and frightened, and I feel kinship with anyone who has shared this ember of the human experience, even if superficially their lives look very different to mine. At 10 years old, I wrote in my diary, “because of what is being done to me, I vow to spend a lifetime helping the helpless and the weak against the powerful bullies.” And I hope my life’s work delivers on at least some of this promise.

Perhaps my ability to grow a useful, and hopefully beautiful, lotus out of the mud comes from sheer good fortune: I just lucked into being genetically predisposed toward happiness and high energy and into having strong psychological muscles. Surely, at least some of my fellow Gen Xers may have emerged psychologically bruised from the roughness with which so many of us were handled. This makes me wonder whether the appearance that the Gen Zers we teach seem considerably more anxious, depressed, and psychologically brittle than us has more to do with their willingness to open up and report about their struggles than with their personalities. But it also has to do with the planetary anxiety (climate crisis, financial crises, political endgame horrors, soul crushing school shooting tragedies) that has characterized their formative years. Either way, the fact is that many of us teachers and mentors encounter young folks who struggle with very powerful demons–depression, anxiety, and others–and that raises serious questions about the extent to which great results can be coaxed out of people through “tough love.”

It’s important not to confuse “tough love” with an uncompromising approach to achievement, or even excellence. I staunchly believe that, by lowering standards, we are misguidedly providing a disservice to the people we try to help. I’ve seen this operate not only in my law school teaching, but also at Balboa Pool, where I work as a lifeguard. Some of my fellow lifeguards teach the Red Cross swim curriculum and are very adamant not to pass children to the next level unless they demonstrate having actually acquired the necessary skills. “They are taking my class,” said one of my colleagues, “not so that their parents will like me, but so that they will know how to swim,” which is not some fancy unimportant frivolous accomplishment: it is an essential lifesaving skill. When the big wave comes for you, you either swim or you don’t. Providing you with the feel-good illusion that can perform a task when you actually cannot is not helping you go forward in life. Similarly, giving you a diploma and a license to practice law when you are incapable of solving other people’s problems with knowledge and confidence is doing a disservice not only to you, but to your clients.

The issue I’m tackling here is quite different: it’s not so much about the standards but about the path toward achieving them. It looks like, at least in athletics (and perhaps in law schools – remember Prof. Kingsfield?) there is a dying breed of old-school coaches and instructors who strongly believe that the way to greatness–Olympic medals, world records, you name it–necessarily requires “toughening people up” through being mean to them. I find myself agnostic: surely some level of toughness and resilience is an important quality to cultivate in people who are aiming at performing and achieving at a high level. But does this really extend to a need to insult and humiliate? The public belittling and verbal punching doesn’t seem to produce the right results in this generation, but did it really prove successful in previous generations? Or did people like Natalie Coughlin, Dana Vollmer, and others accomplish incredible feats despite–rather than because–an atmosphere of toughness and abuse? Could it be that the successful folks were not the one on whose heads the cruelty was rained?

If, with the exposés of Salazar, McKeever, and others, the breed of “tough love” or just “tough” coaches is dying, we certainly have not done enough thinking on whether, and how, to get great results without the great cruelties and indignities. If it is possible, then what is the best model for this? I was very lucky to have, in grad school, the mentorship of Malcolm Feeley, who never once mistreated me, always regarded me as his protégé and friend, and always shone in my skies like a good fatherly sun. To this day I can always count on his steady guiding hand and good advice, and if I have achieved anything in my professional life, it was because, rather than despite, his infinite generosity and kindness. So I know that it can be done, and if a Malcolm-esque model of mentoring could be scaled up to athletics, the world would be better. This, of course, assumes that there’s nothing unique to sports that requires that cruelty be added to the cocktail of instructive styles and methods.

But let’s assume, for a dark teatime of the soul, that it does. Let’s assume that the medals and world records and all that are fueled, to some extent, by the cruelty. That there’s some demonstrable correlation between calling people names and publicly humiliating them and these same people running or swimming very fast and winning races. Do we really care about results so much that we are willing to accept any method for achieving them? Perhaps we’re not there yet. As my friend Aatish suggested in a conversation about this today, “the spectacle demands the next record being broken. No one is going to be all like – oh hey, it’s cool that the mile times will all get slower because now we’re being more ethical.”

And perhaps the same question applies to law school. In the above-linked piece that defends Prof. Kingsfield, Michael Vittielo writes, “Few commentators have asked whether law students are as well prepared today as they were thirty years ago, now that they graduate from far more student-friendly law schools, or whether they are less cynical if they attend law schools where their professors solicit their personal views.” If empirical evidence an be provided that law students are less well prepared now than they were in those rough Socratic method years–can it still be said, “okay, but we’re willing to sacrifice some preparation/proficiency because we don’t want to publicly humiliate our students anymore”?

A strange analogy comes to mind. During the 2008 Beijing Olympics, Speedo pioneered a techsuit called the LZR racer, which was proven statistically to have contributed to the many world records that were broken in the pool. Now, when looking at the record book, all records and results achieved by a swimmer wearing a LZR racer are marked with asterisks. If the analogy isn’t clear, let me spell it out. As more and more evidence of cruelty toward and neglect of young people in sports coaching surfaces, and as more and more of us find it abhorrent and unconscionable to treat people this way even if it produces results, will there ever come a time in which records accomplished partially as a consequence of humiliation and abuse will be marked with an asterisk for posterity, and will no longer be an accomplishment we are willing to tolerate?

Urban Alchemy in the News

SF-based nonprofit Urban Alchemy, which I discussed here and here, is in the news this week. First, there was BBC coverage, and this morning a lengthy investigative story in the Chron. Mallory Moench and Kevin Fagan’s story is interesting and informative, and offers lots of useful perspectives, but does adopt an unnecessarily skeptical emphasis and tone, which rankled me because I work in the Tenderloin and see the transformation it has undergone through Urban Alchemy’s intervention.

In the early pandemic months, the open drug market around my workplace was so brazen and violent that my students feared going out of their dorm rooms at the Hastings towers. Mayor Breed and SFPD tried to resolve the problem by doing police sweeps of the area, which only resulted in new people coming in to deal and shoot every day. At some point I was contacted by a civil rights org, which shall remain anonymous out of compassion, with a well meant, but absurd, invitation to support their lawsuit against gang injunctions with an amicus brief refuting the existence of the drug market. Refuting? I thought. Are you kidding me? Do you have eyes? Do you live or work here? It was a prime example of what I’ve come to recoil from: the refusal, by some quarters of the Bay Area’s delusional left, to concede that crime is real and has real victims and real implications (that’s why I have no patience for armchair abolitionism, by the way.)

Then, our Dean signed a contract with Urban Alchemy, which has them support the area adjacent to the school. This proved to be a complete game changer. The first morning I showed up to work with the UA practitioners surrounding the perimeter of the school I was amazed; the change in energy, the peacefulness, the friendliness, the sense of personal safety, were palpable. I started chatting with some of the practitioners around my workplace, who came from backgrounds of serious incarceration, and found that their personal experiences provided them with just the right interpersonal skills to intervene in complicated situations in the Tenderloin. Finally, someone is doing the right thing, I thought. There are so many occupations in which a background of criminal invovement and incarceration is a priceless resource – and this includes lawyering. Recently, I interviewed people with criminal records who applied to the California bar and wrote:

In the few occasions in which bar membership with criminal records are discussed, it is not in the context of diversity, but rather in the context of a public concern about “crooks” in the legal profession. Accordingly, the bar orients its policies, including the recent requirement that current members undergo periodic fingerprinting, toward the exposure and weeding out of “crooks.” Criminal experiences are seen as a liability and a warning sign about the members’ character.

My interviewees’ interpretations were diametrically opposed to those of the bar. All of them, without exception, mentioned their experiences in the criminal justice system as catalysts for their decision to become lawyers, and most specifically to help disenfranchised population. Public interest lawyers who spoke to me cited their own criminal experience as an important empathy booster with their clients. Even some of the ethics attorneys cited their personal experiences with substance abuse as a bridge between them and clients with similar histories. By contrast, commercial lawyers, especially in big firms, remained circumspect about their history. Two lawyers spoke to me in the early morning hours, when they were alone in the office, and others spoke from home, citing concern about letting their colleagues know about their history. My conclusion from this was that the interviewees’ background was a rich resource that provided them with a unique and important insider perspective on the system, which remained unvalued and tagged as uniformly negative baggage.

To Moench and Fagan’s credit, their piece does represent this view; one of their interviewees explicitly says that looking at justice involvement as an asset, rather than a barrier, is revolutionary. But overall, their reporting exceedingly amplifies the voices of the naysayers above those of the many people who live and work in the Tenderloin who are quietly grateful for Urban Alchemy’s presence in the streets. You’ll be hard pressed to find detail in their story of the many good deeds that the practitioners perform daily, ranging from lives saved with Naloxone (several times a week, I’m told) to skillfully providing my female students a sense of personal safety when walking the Tenderloin in the evening. Several students described how a practitioner subtly positioned himself between them and someone who was getting too close, and how the threatening situation evaporated before it could evolve in unsavory directions. Moench and Fagan give this a passing nod, but their piece fails to properly capture the magic.

This brings me to another observation: There hasn’t yet been a project evaluation for Urban Alchemy’s Tenderloin intervention. Executing such a study would be a daunting task for several methodological reasons. First, there’s no comparative baseline for the intervention. The situation before their intervention was so abnormal that it would be hard to use it as a control, even if data were available. If the comparison is geographic, it would suffer from the usual problems with situational crime prevention: focusing an intervention in a particular geographical zone means that criminal activity is displaced onto adjacent zones, so the two comparators are not independent of each other. If the study is structured as an in-depth phenomenological project (which is what I would do if I were to do this–and a colleague and I are thinking about this), there’s the Star Trek problem of the Prime Directive: researchers or students hanging out in the Tenderloin to conduct observations would, themselves, change the dynamics in the area that they study. A big part of Urban Alchemy’s success lies in the fact that they do things differently than SFPD. They do not rely on surveillance cameras; in fact, they eschew them, and having any sort of documentation would be detrimental to their working model. And people standing in the corner for hours and taking notes would chill everyone’s behavior. Fieldwork here has to be conducted with care.

I have one more observation to offer: I now work in a service profession that requires crowd management and interpersonal intervention (as a city pool lifeguard) and also have multiple years of experience managing crowds in rowdy, inebriated, unusual situations (as a Dykes on Bikes registration volunteer at Pride and at Folsom Street Fair, for example.) The vast majority of people you encounter at these settings are lovely and a delight to be with. But the one or two percent who are decidedly not lovely can really test anyone’s self control. I’m talking about the driver who insists on driving the car into the area you’re trying to cordone off, the slow dude who insists on swimming in the lane with faster people and not letting them pass, or the people repeatedly told (politely) to move to the sidewalk so that they are not run over by trucks who don’t go where they’re told. My experiences are nothing compared to what the Urban Alchemy practitioners encounter every day on the Tenderloin streets. I really wish our reporting on this were sympathetic to the enormous challenges of interpersonal interactions in this very rough patch of our city and more appreciative of how much conflict and anxiety are spared when people who know what they’re doing take the lead.

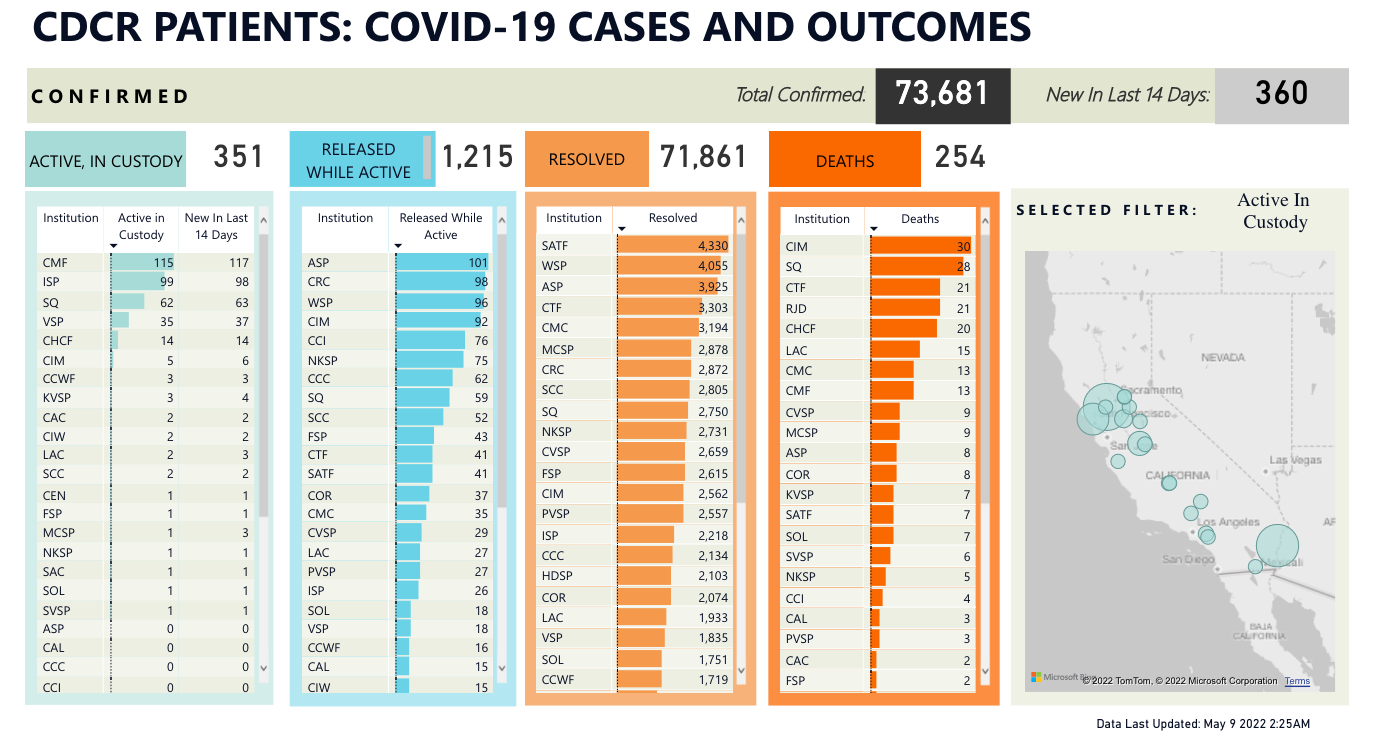

The Latest on COVID-19 in Prisons and Jails

Lest anyone think that the COVID scourge is gone from California prisons, this morning’s ticker shows 351 active cases, 62 of which are at San Quentin. There are also, at the moment, 261 active cases among employees.