There’s a really interesting op-ed by Jeff Asher and Ben Horwitz of AP Analytics in yesterday’s USA Today about the 2020 rise in homicide rates. Here’s an excerpt:

The FBI reported in September that murder was up almost 15% in agencies that reported three to six months of comparable data for both 2019 and 2020. But the antiquated national crime data collection and reporting system makes it hard to confidently say what is causing the spike or what can be done about it.

The FBI has used the Uniform Crime Reporting Summary Reporting System, which was created in 1929, for the past nine decades. There are about 18,000 law enforcement agencies in the United States. Only a bit more than 16,000 of them reported monthly crime figures last year in eight relatively broad categories that the FBI aggregated and published. This annual collection system is shoddy. Some agencies don’t report data every year and others report incomplete data.

There have been changes over the decades, but crime data reporting is mostly the same today as it was 90 years ago. And the most glaring issues remain: Agencies aren’t required to report data, and those that do report are often not asked to provide data in a way that’s useful. For example, agencies aren’t required to separate assaults during which individuals are shot from other attempted aggravated assaults by firearm. In general, assault-by-firearm cases are massively underreported, severely reducing insight into national gun violence trends.

Efforts have been made to improve collection, but there is still no timely national crime data. The FBI’s report in September was the first time the bureau produced a quarterly summary report.

The FBI also built a website that improves access to raw crime data, and in January the agency will drop the summary reporting system and transition solely to a National Incident Based Reporting System (NIBRS), which will provide a more nuanced look at trends.

The incident-based reporting system categorizes crime into more than 52 offense types, which provide more insight into the types of crimes recorded. But that system, while better, won’t solve all crime data reporting problems. Shootings, for example, will still not be specifically categorized under NIBRS.

It is also unclear how many agencies will participate in NIBRS next year. Just 51% of the participating agencies reported under NIBRS as of 2019. The switch to NIBRS-only doesn’t appear to solve the problem of lengthy delays in reporting crime data to the public.

The 2019 stats, for example, weren’t released until the end of this year.

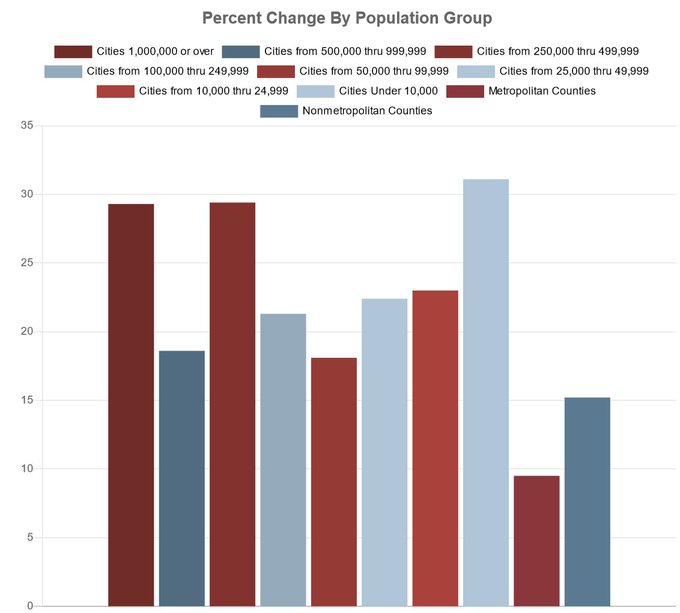

Even though the FBI data is shoddy (for which, to be sure, there’s no excuse), there are a few things we can learn from this. On Twitter this morning, Asher provided the graph at the top of this post to show that the upward trend is consistent in lots of different towns, and he also has numbers to show that it’s not a Democratic/Republican issue (cities run by both R and D administrations are seeing a rise in crime.) He also showed that the rise in homicides is accelerating over the first three quarters of 2020, refuting one-factor explanations (“this is all about Defund the Police!”).

I’m still (STILL!) grading exams, so I don’t have the bandwidth to do a full analysis on the data (you can download the entire dataset here and be your own hero) but I do have three quick observations to make:

- The data provides a breakdown by serious offense, but has a monolithic category of “murder,” preventing us from analyzing different types of murder. Even though it looks like a uniform rise as 2020 progressed, it is not implausible to suggest that the type of homicides that increased during the pandemic lockdown might be different. My money’s on a higher percentage of domestic homicides, and this might be something that can be confirmed by correlating with rapes and assaults. The reasons are obvious–all the risk factors for domestic violence are heightened because of the pandemic and the ensuing financial crisis: stress, proximity to assailant (especially the availability of children and working spouses during the day), unemployment, financial difficulties. It’s also possible that a higher consumption of drugs, more mental instability, and more people in the streets leads to more street shootings. None of this is rocket science.

- Articles about the rise in homicides in SF and Oakland highlighted that the incidents involve an overrepresentation of victims of color (the articles say nothing about perpetrators, but homicide tends to be intraracial.) If my theory that Q2 and Q3 largely represent a rise in domestic homicides, it should come as no particular surprise that you’d see higher rates of homicide among the populations that were disproportionately impacted by the pandemic and the prevention regimes (more stress, more unemployment, more financial difficulties, more homelessness, more mental health anguish visited on poor people of color.)

- I’m already seeing some lazy takes on Twitter about whether “this could have been caused my mass releases,” to which the easy answer is: What mass releases? The rise in homicides far precedes any releases that were taking place–even to the extent that some places (not CA!) released people, no one was heeding warnings from experts back in March, when the rate of homicides was already accelerating. Moreover, the acceleration is linear, suggesting that if releases in, say, July and August changed things in Q3, they didn’t do so to a particularly pronounced degree that was not predictable by the general trend. Nor is there anything to suggest that the people who were released–in CA, basically folks who would be released anyway due to attrition rates who got a wee push out the door a couple months early–can trigger a trend like this, and for places who did do their due diligence in releasing aging and infirm folks, those are the least likely people to commit crime, let alone homicide.

I’m harping on (3) for a reason. My suspicion is that we are not seeing mass releases precisely because of the fear that the inevitable rise in crime rates as a consequence of pandemic-related criminogenic factors will be linked by lazy journalists and hobbyist twitterers to releases (even though it likely has nothing to do with releases) and backfire in terms of political advancement. This is disappointing, but it is how democracy works, and the first people to suffer are the folks already behind bars–solely for the sake of optics.