I’m very much looking forward to my seminar today, in which we’ll be discussing Daniel Okrent‘s recent book Last Call, a detailed, vivid, darkly humorous and politically insightful analysis of the rise and fall of Prohibition. I can’t recommend it enough, and very much hope my students enjoyed it as much as I did.

In Last Call, Okrent provides an informed history of the emergence of Prohibition. Contrary to some popular notions, according to which the temperance movement was largely a religious movement, prohibition was the result of a narrow coalition between a variety of social and political groups with conflicting political interests, all of which were served in this way or another by a ban on alcohol consumption. The most important and surprising of these allies was the movement for women’s suffrage; in fact, many of the important heroines of the suffragette movement joined the cause so that a vote could be cast against alcohol. Alcohol consumption was directly related to gender issues, as the United States had been, for years, awash with drink, and saloon culture was tied to domestic violence, squandering of the family budget, and prostitution. But there were other interesting allies as well. Racism found a home in the temperance movement, as well; just as with the criminalization of drugs, some concerns about alcohol were dressed as the fear of the hypersexualized black, violent man, while other concerns arose in the context of Irish Catholics. And, as with various criminalizing “wars” of later times, the deeply-felt effects of World War I, before, during and after the war, played into the debate, fueling an antipathy toward Germanism, which manifested itself as antipathy toward German distillers and brewers.

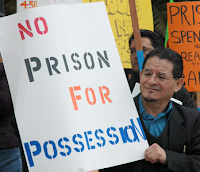

The delicate dance between taxing and criminalizing vices, which we spend so much time reflecting on in the context of narcotics, was very present in the Prohibition debate. In fact, the passage of the Eighteenth Amendment was facilitated by a prior revival of the alcohol excise tax. As with the Harrison narcotics act, any form of ceding ground of individual freedoms and making them subject to federal regulation later allowed greater curtailment of these rights, resulting in one of the two only constitutional amendments forbidding people from doing something (the other one is slave ownership.)

We all know, of course, that prohibition failed, and that it had something to do with lax enforcement and with an underworld economy of booze; but Okrent’s book provides enormous insight into how lax enforcement was. Not only was manpower limited and the ability to follow up the powerful underworld economy therefore limited, but the government actually created rather wide exceptions to prohibition. The book’s delving into the world of “medical alcohol” will remind many Californian readers of the medical marijuana regime.

Was prohibition a success or a failure? We tend to regard it as a failure. But I think that, given the immense obstacles in the way of criminalizing a so-called victimless crime, nation-wide, the coalition for prohibition was an astonishingly successful enterprise. That, for a moment in time, racists and progressive working unions, suffragettes and anti-immigrant activists, managed to put their differences aside and lobby for a change in law, is nothing short of astonishing, and very hard to imagine in today’s partisan, polarized political world. In some ways, it makes it more interesting to watch the upcoming elections in November, to see whether Prop 34’s proponents will be successful in their efforts to get together former correctional staff, law enforcement officials, victim organizations and inmate rights groups to support the replacement of the death penalty with life without parole.

As a coda, enjoy this witty interview of Okrent on The Daily Show.

| The Daily Show with Jon Stewart | Mon – Thurs 11p / 10c | |||

| Daniel Okrent | ||||

|

||||