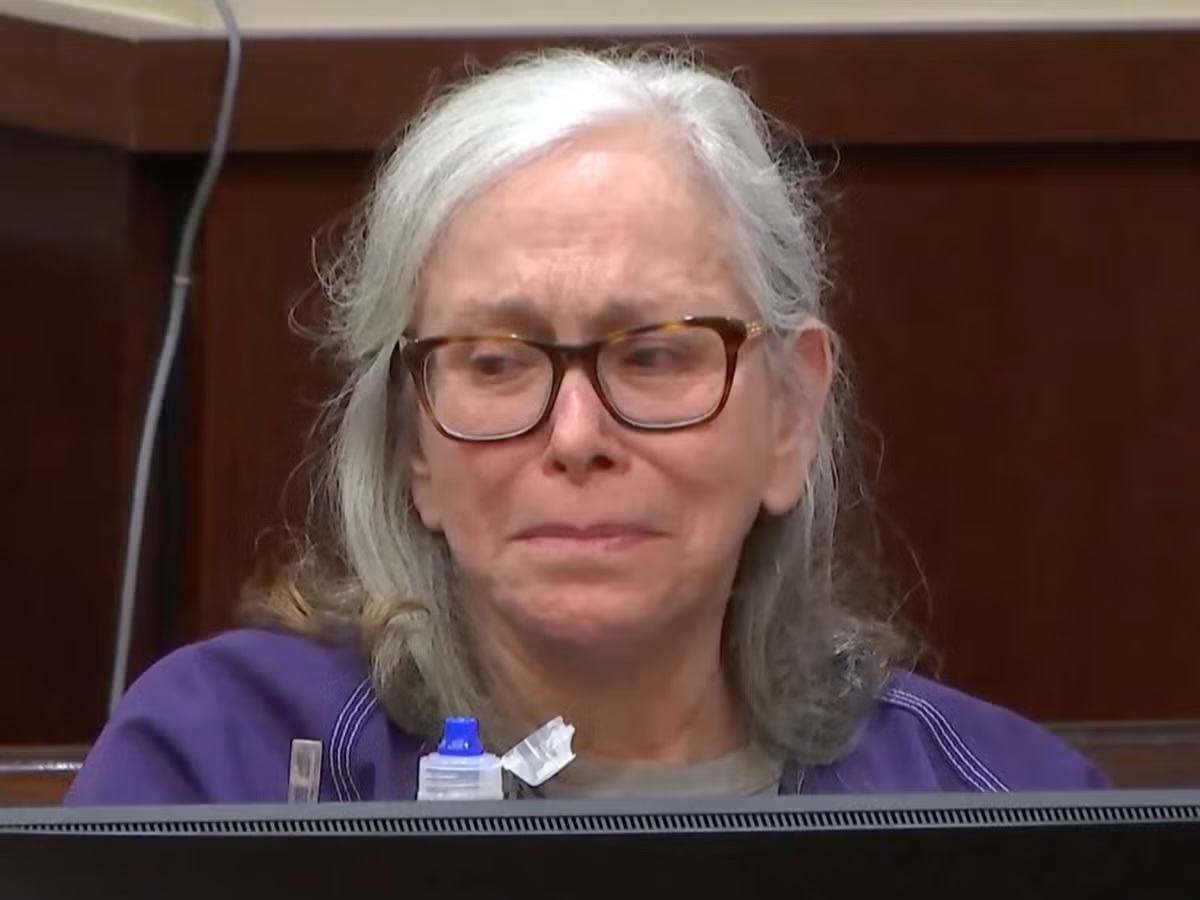

On Monday, Donna Adelson, who was convicted of her role in the murder of my colleague Dan Markel, was sentenced to life in prison. Several people testified in her defense, including her husband Harvey and a family friend who had also testified at the trial. Donna herself gave a lengthy unsworn statement, which you can hear for yourself here:

What is the value of such a statement? We know that the rules of the game are much looser at the sentencing phase than they are at the guilt phase; evidentiary limitations, such as the hearsay rule, do not apply. Still, under Florida law, sentencing witnesses must be sworn in. Theoretically, these witnesses can be cross examined and impeached, but I suspect that at this point, unless there are glaring falsehoods, the prosecution is happy to have the judge form their own impression of the reliability of the testimony.

The one sentencing witness who need not be sworn in is the defendant, who may give an allocution statement and is not cross examined on it. But using the opportunity to offer such a statement–especially after electing not to testify at the guilt phase–can be a double-edged sword. On one hand, it is commonplace for judges to consider the defendant’s remorse as a mitigating factor. Given that the defendant was found guilty, the judge operates under the understanding that legal truth equals factual truth, and thus a defendant professing innocence is an unrepentant defendant who deserves no mitigation (this is what happened here). On the other hand, despite this risk, for some people it pays off to continue to profess their innocence, for various reasons:

- Perhaps they are innocent! Dan Simon conservatively estimates that 5% of all criminal defendants are innocent. A person wants to preserve their moral integrity.

- Perhaps they feel indignation or entitlement about other injustices in the process and do not feel guilty even if they are.

- Perhaps they are performing to family/friends and other people. This is especially common when one is convicted of heinous offenses, such as sex crimes or violent crimes, and wants to preserve their reputation vis-a-vis those close to them.

- Perhaps they want to preserve some issues for postconviction procedures (in some cases, a consistent claim of actual innocence can play a small but important part in federal habeas).

- Perhaps they (mis)calculate that the judge was not fully persuaded by the jury’s verdict and might be responsive to their plea of innocence.

- Perhaps this will play off well in the long run, in that a change of heart and a later acceptance of responsibility can pay off in sentence reduction deals (e.g., I will accept responsibility and testify against a co-conspirator or accomplice in return for a reduction in sentence; otherwise, I will insist that both they and I had nothing to do with the crime) or on parole (e.g., I’ve gone through an amazing moral transformation in prison and learned to accept responsibility for my crime).

Since I very much doubt the first factor in this list is plausible in Adelson’s case, I wonder if the other factors are relevant here; specifically, whether Donna is saving a change of heart (similar to Katie Magbanua’s) for a time at which Wendy and/or Harvey face trial. In any case, lashing against the jury and the judge, claiming bias and/or inattention, as both Donna and Harvey did at the hearing, does not seem to be the right mindset to engender any sort of sympathy. Perhaps the habit of a lifetime–lying, acting entitled, believing that one is always in the right and everyone else is in the wrong–simply proved too hard to shake.