Dear Gov. Newsom,

More than a decade ago you showed courage, initiative, and deep commitment to human rights and dignity when, as Mayor of San Francisco, you opened the door to same-sex marriages. As Governor, you showed the same courage and commitment in deciding to place a moratorium on the death penalty in California.

As criminal justice and corrections scholars, we are writing to urge you to once again do the right thing. Throughout California, COVID-19 infections, hospitalizations, and deaths are ravaging state prisons. As of July 6, 5,343 people in California prisons have tested positive for COVID-19, 25 people have died, and hundreds are struggling with active symptoms and hospitalizations. At San Quentin Prison, a botched transfer from the California Institute of Men allowed the virus to spread like wildfire, with 1,421 people who have tested positive.

A recent report on San Quentin Prison from a team of UCSF physicians revealed flawed, negligent protocols for isolation and treatment, lack of consistent and updated testing, unconscionable delay in providing testing results, inappropriate grouping of staff members, and physical locations for isolations that are terrifying and alienating to the population. These inadequate practices are happening against the backdrop of prisons already bursting at the seams, with many of them overcrowded not only well beyond their design capacity, but over the 137.5% limitation set for the entire correctional system by federal courts more than a decade ago.

The men and women in California prisons are serving sentences meted out by law. The California Penal Code did not sentence them to neglect, abuse, illness at overcrowded institutions with the potential to become mass graveyards. As to those falling ill and dying on death row, surely your moratorium on the death penalty, and the decades and billions of dollars spent litigating capital punishment protocols, should not end with deaths by COVID-19.

Moreover, COVID-19 infection is not a zero-sum game, and prioritizing the prison crisis does not come at the expense of the state overall — rather, it protects all of us. In both Marin and Lassen counties, spikes in community infections followed closely after spikes in infection within state prisons; all correctional institutions are permeable to the outside through staff mobility. Protecting people in prison protects people outside prison, too. By contrast, incubating the virus at our state prisons puts the entire state at risk, potentially rendering all your important prevention work, all the efforts at public education about masks and social distancing, and the immense sacrifices of all Californians futile.

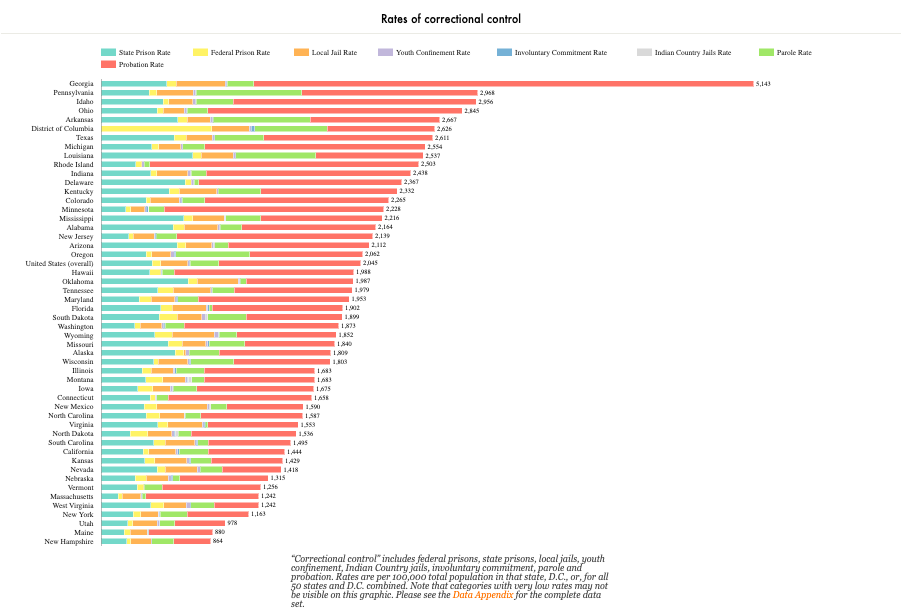

We urge you to exercise all the powers at your disposal and release people from prisons to their communities — not just at San Quentin, but systemwide. Given the overcrowding and contagion spread, the release of a few thousands is but a drop in the bucket. A robust body of research in our field confirms that such releases, via executive orders, clemency, and parole (hundreds who have been found eligible for parole are still behind bars), will not endanger public safety. A quarter of the California prison population is aged 50 years and older; this population consists largely of people whose crimes of commitment were committed decades ago, and who do not pose any public risk, violent or otherwise. Previous declines in the California prison population, through the Criminal Justice Realignment and through Prop. 47, did not put the public at risk. We urge you to follow solid findings in criminology, public policy, criminal justice, and public health, rather than misleading and fear-mongering media reports.

We appreciate and admire your willingness to courageously do the right thing in previous pivotal moments; your initiative on same-sex marriage and on the death penalty moratorium have shown your prescience and will be remembered kindly by history. This is precisely such a moment. We urge you to lead us in the right direction.

Respectfully,

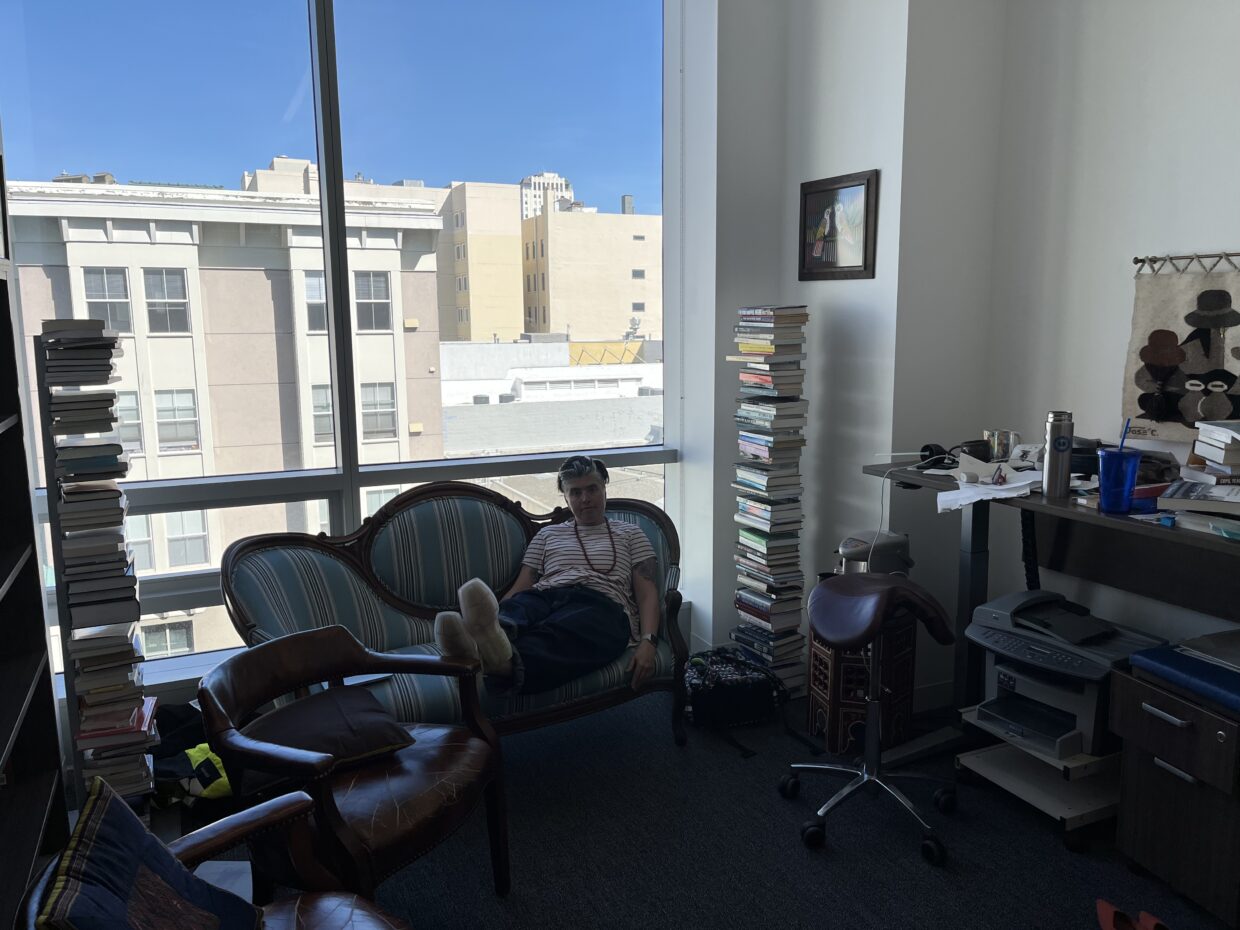

Hadar Aviram, Thomas E. Miller ’73 Professor of Law, UC Hastings College of the Law

Sharon Dolovich, Professor of Law and Director, UCLA Law Covid-19 Behind Bars Data Project, UCLA School of Law

Aaron Littman, Binder Clinical Teaching Fellow and Deputy Director, UCLA Law Covid-19 Behind Bars Data Project, UCLA School of Law

Susan Coutin, Professor, Criminology, Law and Society, UC Irvine

Arielle W. Tolman, Law and Science Fellow, Northwestern University

Adelina Iftene, Assistant Professor, Schulich School of Law at Dalhousie University

Michael Gibson-Light, Assistant Professor of Sociology & Criminology, University of Denver

Valena Beety, Professor of Law, Arizona State University Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law

W. David Ball, Professor, Santa Clara School of Law

Keramet Reiter, Associate Professor, Criminology, Law & Society, University of California, Irvine

Zachary Psick, Graduate Student, UC Davis

Nicole Kaufman, Assistant Professor of Sociology, Ohio University

Kitty Calavita, Chancellor’s Professor Emerita, UC Irvine

Susila Gurusami, Assistant Professor of Criminology, Law, and Justice at UIC (UCLA doctoral alum)

Angela P. Harris, Professor Emerita, UC Davis School of Law

Tasha Hill, Managing Attorney, The Hill Law Firm

Gabriela Gonzalez, Doctoral Candidate, University of California, Irvine

Aya Gruber, Professor, University of Colorado Law School

Shannon Gleeson, Associate Professor, Cornell University

Melissa McCall J.D., PhD Student, UC Berkeley Law

Gennifer Furst, Professor, Sociology & Criminal Justice, William Paterson University of NJ

Dvir Yogev, PhD student, UC Berkeley

Caity Curry, PhD Candidate, University of Minnesota

Alessandro De Giorgi, Professor, Department of Justice Studies, SJSU

Brett Burkhardt, Associate Professor, Oregon State University

Russell Rickford, Assoc. Prof. of History, Cornell University

Brianna Remster, Associate Professor of Sociology and Criminology, Villanova University

Aaron Kupchik, Professor of Sociology and Criminal Justice, University of Delaware

Sarah Russell, Professor of Law, Quinnipiac University School of Law

Caitlin Henry, Esq., Faculty, Criminology and Criminal Justice Studies, Sonoma State University

Issa Kohler-Hausmann, Professor, Yale Law School

Sharon Dolovich, Professor of Law and Director, UCLA Law Covid-19 Behind Bars Data Project, UCLA School of Law

Naomi Sugie, Associate Professor, University of California, Irvine

Beth A. Colgan, Professor of Law, UCLA School of Law

Hope Metcalf, Clinical Lecturer in Law, Yale Law School

Jonathan Simon, Professor of Law, UC Berkeley

Victoria Piehowski, PhD Candidate, University of Minnesota

Shira Shavit MD, Clinical Professor, UCSF

Isaac Dalke, Graduate Student, UC-Berkeley

Kristin Turney, Associate Professor, University of California, Irvine

Christopher Seeds, Assistant Professor, University of California-Irvine

Joshua Page, Associate Professor, University of Minnesota

Franklin Zimring, Simon Professor of Law, University of California at Berkeley

Elizabeth Brown, Professor, San Francisco State University

Daria Roithmayr, Professor of Law, University of Southern California Gould School of Law

David Garland, Arthur T Vanderbilt Professor of Law, NYU School of Law

Laura Gomez, Professor, UCLA

Nikki Jones, Professor, UC Berkeley

Chrysanthi Leon, Associate Professor, University of Delaware

Ingrid Eagly, Professor, UCLA School of Law

Sarah Smith, Assistant Professor, California State University, Chico

Keith P. Feldman, Associate Professor of Ethnic Studies, UC Berkeley

Jessica Cooper, Lecturer in Social Anthropology, University of Edinburgh

Vanessa Barker, Professor, Stockholm University

Valerio Bacak, Professor, Rutgers University

Jackson Smith, PhD Candidate, New York University

Benjamin Fleury-Steiner, Professor of Sociology and Criminal Justice, University of Delaware

Colleen Berryessa, Assistant Professor, Rutgers University School of Criminal Justice

Nicole B. Godfrey, Visiting Assistant Professor, University of Denver Sturm College of Law

Mariella Pittari, Public Defender — Brazil, Ph.D. Candidate University of Turin, Italy

Scott Cummings, Professor of Law, UCLA School of Law

Catherine M. Grosso, Professor of Law, Michigan State University College of Law

Sebastián Sclofsky, Assistant Professor, CSU Stanislaus

Chloe Haimson, Sociology PhD Student, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Jodi L. Short, The Hon. Roger J. Traynor Chair & Professor of Law, UC Hastings Law

Gabriela Kirk, Graduate Student, Northwestern University

Matthew Canfield, Assistant Professor, Drake University

Julie Novkov, Professor, University at Albany, SUNY

Qudsia Mirza, Birkbeck, University of London

Lydia Pelot-Hobbs, Postdoctoral Fellow, Prison Education Program New York University

Danielle S. Rudes, Associate Professor, George Mason University

Alex Aguirre, PhD Student, UC Irvine

Paul A. Passavant, Associate Professor, Hobart and William Smith Colleges

Lauren McCarthy, Associate Professor, University of Massachusetts Amherst

Tracey Roberts, Associate Professor, Samford University, Cumberland School of Law

Menaka Raguparan, Assistant Professor, UNCW

Lindsay Smith, Graduate Research Assistant, George Mason University

Mona Lynch, Professor of Criminology, Law & Society, UC Irvine

Christine Harrington, Professor, NYU

Lisa L. Miller, Rutgers University

Heather Schoenfeld, Associate Professor, Boston University

Alex Rowland, PhD Student, University of California Irvine

Thea Johnson, Associate Professor, Rutgers Law School

Stephen Gasteyer, Assoc. Professor of Sociology, Michigan State University

Amanda Petersen, Assistant Professor, Old Dominion University

Brittany Arsiniega, Assistant Professor of Politics and International Affairs, Furman University

Dr. Ciara O’Connell, Trinity College Dublin, Ireland

Dr. Orna Alyagon Darr, Sapir College Law School (Israel)

Jill McCorkel, Professor of Sociology and Criminology, Villanova University

Mary R Rose, Associate Professor, University of Texas at Austin

Smadar Ben-Natan, adjunct professor, UC Berkeley

Heather Elliott, Alumni, Class of ’36 Professor of Law, University of Alabama

Jack Jin Gary Lee, Visiting Assistant Professor of Sociology and Legal Studies, Kenyon College

Jason Sexton, Visiting Research Fellow, UCLA’s California Center for Sustainable Communities

Li Sian Goh, Research Associate, Institute for State and Local Governance

Anna Reosti, Research Professor, American Bar Foundation

David Levine, Professor of Law, UC Hastings College of the Law

Tina Lee, Associate Professor of Anthropology, University of Wisconsin-Stout

Rosann Greenspan, PhD, Executive Director (Retired), Center for the Study of Law and Society, UC Berkeley School of Law

Rebecca Bratspies, Professor, CUNY School of Law

Jonathan Marshall, Director, Legal Studies Program, UC Berkeley

Eliana Branco, PhD, University of Coimbra, Portugal

Shelley Tuazon Guyton, Graduate Student, UC Riverside

Maryanne Alderson, Doctoral Student, University of California, Irvine

Nina Chernoff, Professor, CUNY School of Law

Hana Shepherd, Assistant Professor of Sociology, Rutgers University

Smita Ghosh, Research Fellow, Georgetown University Law Center

Carrie Rosenbaum, Lecturer, UC Berkeley

Niina Vuolajarvi, Rutgers University

Jane McElligott, Professor, Purdue University Global

Elizabeth L. MacDowell, Professor of Law, University of Nevada Las Vegas

William Darwall, PhD Student, Berkeley Law

Allie Robbins, Associate Professor of Law, CUNY School of Law

Michelle Phelps, Associate Professor of Sociology and Law, University of Minnesota

Justin Marceau, Professor, University of Denver

Christina Matzen, PhD Candidate, University of Toronto

Tony Platt, Distinguished Affiliated Scholar, Center for the Study of Law & Society, UC Berkeley

Christopher Slobogin, Milton Underwood Professor of Law, Vanderbilt University

Erin Hatton, Associate Professor, University at Buffalo

Michael McCann, Professor, University of Washington

Marina Bell, PhD Candidate, University of California, Irvine

David Green, Associate Professor, John Jay College of Criminal Justice

Toussaint Losier, Assistant Professor, University of Massachusetts — Amherst

Dan Berger, associate professor of comparative ethnic studies, University of Washington Bothell

Sarah Kahn

Rebecca Tublitz, Doctoral Student, University of Californa, Irvine

Meghan Ballard, Graduate Student, University of California, Irvine

Jocelyn Simonson, Professor, Brooklyn Law School

Lisa McGirr, Professor of History, Harvard University

Courtney Echols, PhD Student, Criminology, Law & Society, University of California, Irvine

Susan M. Reverby, Professor Emerita, Wellesley College

Julilly Kohler-Hausmann, Associate Professor, Cornell University

Tal Kastner, Jacobson Fellow in Law and Business, New York University School of Law

Elizabeth Wilhelm, PhD student, University of Kansas

Sheri-Lynn S. Kurisu, PhD; California State University San Marcos; Assistant Professor

Timothy Stewart-Winter, Associate Professor of History, Rutgers University-Newark

Joss Greene, PhD student, Columbia University

Kimberly D. Richman, Professor, University of San Francisco

Matthew Canfield, Assistant Professor, Drake University

Dallas Augustine, Ph.D. Candidate at UC Irvine; Research Associate at UCSF

Leigh Goodmark, Professor, University of Maryland

David Greenberg, Professor, New York University

Full text of letter, plus updated list of signatories, posted to Medium here. Scholars who wish to join are welcome to email me with their name, title, and affiliation.