Currently, the California Constitution, in Article II, Section 4, provides that “The Legislature shall. . . provide for the disqualification of electors while . . . imprisoned or on parole for the conviction of a felony.”

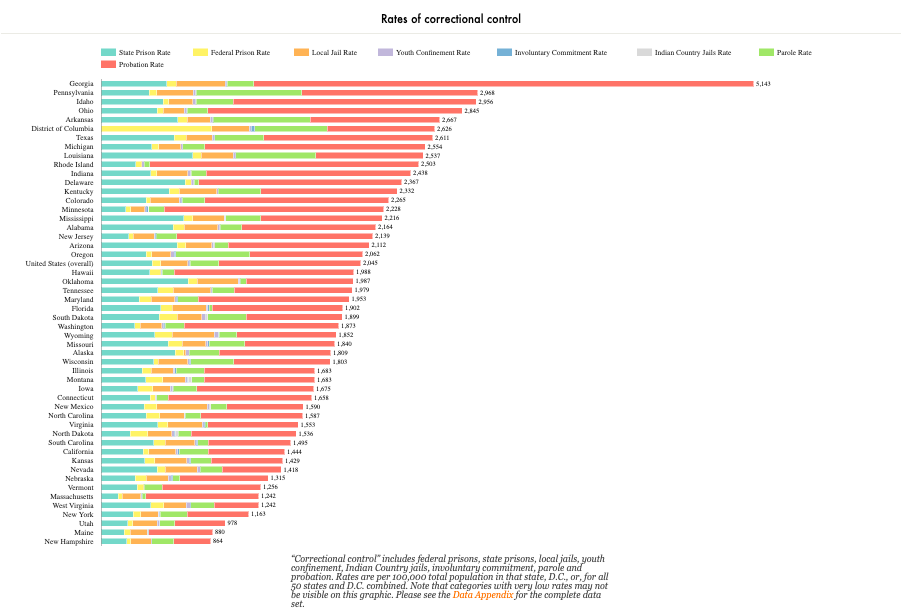

Accordingly, people who are serving a sentence in a state or federal prison, or have been released and are on parole, cannot be registered to vote. As of 2016–after our litigation efforts to get it done sooner failed–this restriction does not include people who are doing time in jail, even for felonies, nor does it include folks on community probation. But this leaves people on parole disenfranchised. According to the Prison Policy Initiative, as of Dec. 31, 2016, there were 89,586 people on parole. This is not a big number, because after Realignment, most people with felony convictions are supervised by the counties in the community (in addition to the already existing large probation population)–as of Dec. 31, 2016, we had 235,918 on probation. According to the Yes on 17 campaign, the number of parolees now is even smaller–they estimate that 50,000 people on parole are ineligible to vote under the CA constitution.

Prop 17 would change that. It is a Constitutional amendment that would grant people who served a federal or state prison sentence the right to vote as soon as they complete their sentence. If we pass this proposition, we’ll join the following states, which allow parolees to vote: Hawaii, Illinois, Indiana, Maine, Massachusetts, Michigan, Montana, New Hampshire, North Dakota, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Utah, Vermont, and D.C.

A “yes” vote on 17 has many benefits. As Jessica Willis and I wrote elsewhere, civic reengagement of people after they return home from a prison sentence is a crucial step in restoring their trust, loyalty, and sense of a stake in their community. It makes communities safer by ameliorating the already-difficult trajectory of reentry and reducing recidivism. It mitigates racial injustices (most parolees are people of color.) And it brings much-needed perspectives, with important experiences, into the democratic process, which includes voting for people like prosecutors and judges.

If anything, Prop 17 does not go far enough–like everyone else, the person would need to register to vote, which is an extra step that creates a hindrance; if it passes, many people might not even know, upon release, that they are eligible to vote. But this goes to my general gripe with a system that requires registering to vote, as opposed to rendering all citizens automatically eligible to vote when they reach voting age; I’ve written before about how U.S. illogical obstinance about a simple measure–the provision of a national identity card to every American citizen when they turn 18–perpetuates a problem that is very easy to solve. But even within the constraints of the existing system (every country has tics and wrinkles–the ones here are obvious to me because I didn’t grow up here,) I can see a solution. When I became a citizen in 2015, as soon as all of us new Americans exited the beautiful Paramount Theatre where our naturalization ceremony was held, we passed through three booths: passport application, social security application, and a happy and energetic voter registration posse. Putting together a similar setup at the exit door of the prison is a piece of cake. All CDCR needs is a computer with a working Internet connection and this handy link, and everyone–EVERYONE–on the day of their release can leave CDCR facilities as a registered voter. As to the expense involved in doing all this, LAO estimates a one-time expense in updating state systems, followed by an annual expense representing the need to print and mail additional ballots and voter materials–exactly what you and I get as registered voters.

There really are no downsides, unless you’re a moralistic curmudgeon who for some reason believes that we should continue disenfranchising people after they’ve served their prison sentence. Let’s bring more people into our democracy. Vote Yes on 17.