The new Netflix original series, Orange is the New Black, is a dramatization of a book by the same name by Piper Kerman (referred to as Piper Chapman in the series), who a few years ago served fifteen months in a federal prison camp for her role in a drug trafficking conspiracy.

Kerman’s story, while not imaginary, is fairly unique. In her early twenties, through her romantic involvement with a woman who worked for an international drug cartel, she helped deliver money internationally. When the relationship disintegrated, so did Kerman’s involvement in the cartel, and she moved on to live a normative, white, middle-class life and get engaged to a man who did not know of her past. Then, ten years after the commission of the offense, the FBI knocked on the door; Kerman’s involvement in the cartel was exposed, and she ended up pleading guilty and being sentenced to fifteen months in federal prison.

The first season of the show, which now streams on Netflix, walks us through the beginning of Chapman’s imprisonment, from her initial surrender at camp through her adjustment to prison life. We are introduced to the other inmates and guards, to prison dynamics, and to the mix of cruelty and compassion that is part and parcel of the incarceration experience.

A few notable examples of the show’s excellent storytelling include the racial divisions among the women and the way the prison system itself uses them to divide the inmates; the underground economy of prison; and the informal socialization mechanisms behind bars. Particularly notable is the show’s attention to sexual assault on the part of the guards, which is a very unfortunate and prevalent aspect of women’s incarceration. One episode draws an analogy between the birth experience of one of Piper’s friends on the “outside” and one of her fellow inmates, taken to the hospital in shackles and returning to prison without her baby. While the show portrays romance behind bars, it steers clear from the lesbian inmate sensationalism that usually characterizes women’s prison dramas and empathizes with the need for human connection. And, while not depicting the many complexities involved in incarcerating trans women (and the practices of administrative segregation involved), it is particularly sensitive to a trans woman’s plight at receiving decent health care in prison.

Because the timing of the show coincided with the California inmate hunger strike, Episode Nine, which depicts the show’s main protagonist spending a night at the SHU, was particularly poignant. Her stay there is portrayed as a frightening, dehumanizing experience. And while there, she speaks through the wall to another inmate–or is it a ghost?–who has lost count of how long she has been there. The terror, isolation and grief involved in the experience has moved many viewers to tears, and I have gotten many inquiries about whether the SHU “is really like this” (it’s much worse and for much longer periods of time.)

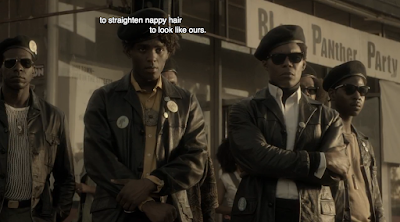

Some critique has been leveled at the show’s portrayal of race and class, arguing that black and brown nudity is treated more licentiously than white nudity. There has also been a concern that the show negatively portrays poor and working class women, in a way that is inattentive to the history of black activism. While the former point bothered me, too, when I watched the show, the latter point reminded me a little bit of the complaints leveled, a few years ago, at the American version of Queer as Folk: Not representative enough, not complimentary to Every Gay Person on the Planet, not educational in the manner of a Very Special Episode of a teenage drama or a carefully-racially-balanced Benetton commercial.

I didn’t find the show remiss in its portrayal of politics behind bars. Yes, there’s a history of racial and social activism in prison. But to argue that, in presenting a federal prison camp the series is remiss in not presenting inmates of color as activists is to ignore the realities of prison. Activism and uprising are the exception, not the norm (this is what is making the California hunger strike, now entering its 17th day, so notable). While many inmates develop consciousness regarding their experience and its broader meaning, incarceration is a difficult experience and for most people “doing time” does not involve political activism. This also goes to the portrayal of race in the show: uniting in the struggle front across barriers of race is also an exception. And, at least in the context of the hunger strike, it’s not the result of some form of racial enlightenment, but rather a response to abysmal, inconceivably degrading prison conditions that offend people’s dignity beyond their racial alliances.

As to the main critique against the show–its atypical narrator and removal from the class/race experience of prison–I think it is important to keep the potential audience in mind. Indeed, while Kerman/Chapman’s story is atypical in terms of her background, introducing the viewers to prison through her eyes is a masterful storytelling device. The passage, by referendum, of so much punitive legislation illustrates how few middle-class taxpayers humanize, and empathize with, the prison population. Even the powerful stories of exonerated inmates haven’t made nearly as much impact as they should, because the average citizen simply cannot imagine himself or herself suffering such indignity. This lack of imagination is startling, considering that 1 in 100 Americans is behind bars, but as we know, that share is not randomly distributed among the population. My experience in explicating the realities of incarceration is that spewing the overworked “prison industrial complex” cliche at white middle-class voters does nothing to deepen their understanding and empathy. On the other hand, giving them a character they can identify with–a woman who, to them, does not “naturally belong” behind bars–can do wonders for their ability to imagine themselves in such a setting. Moreover, while the story is told from a white, middle-class woman perspective, all of its characters come to life as complex, interesting women, aspects of their lives before incarceration shown in flashbacks, and their interactions with each other offered authentically and believably.

Does Orange is the New Black tell viewers everything they need to know about incarceration in America? Of course not. It portrays a federal prison camp of women and does not expose its viewers to overcrowding. Its exposure of SHU isolation practices is menacing, but minimal. And its engagement with the literature on prison politics and economics is superficial. But television cannot educate without entertaining, and judging from the immense interest this series has provoked, it is doing its job as well as can be expected. Many people who did not know about the hunger strike have now resolved to educate themselves and understand it better. Just seeing one night in the SHU on screen will help millions of viewers try to imagine what it could be like to spend five, ten, twenty, thirty years without seeing a living soul. If that raises consciousness and awareness to one of the biggest human rights struggles in America, I will be more than pleased.

Finally, those seeking a more realistic dimension to complement their perception of the prison experience for women should read Inside This Place, Not Of It, which drives home the frightening prevalence of sexual abuse by guards and of atrocious health care practices.

_________

Props to RJ Johnson for providing fodder for this review through the lively discussion on his Facebook page.