Conspiracies and evil machinations have been on my mind lately, for a combination of reasons. One of them is that I recently gave a post-play talk at Cutting Ball Theater‘s production of Superheroes, a play by Sean San José performed in collaboration with Campo Santo. The play is a non-narrative, nonlinear take on the 1996 revelations of Gary Webb, then a journalist with the San Jose Mercury News. In a three-part series of articles titled Dark Alliance (later to appear as a book), Webb outlined the emergence of the crack cocaine epidemic in America’s inner cities. According to the story, CIA agents allowed Nicaraguans who financed the Contras to import cocaine into the United States with impunity and protected mid-level drug dealers from the consequences.

That the CIA was aware of drug importing was already known at the time; a 1989 Senate committee admitted as much, but stopped short of tying the CIA to the actual trafficking. Webb’s article provided the missing link. In response, the New York Times, the Washington Post, and the Los Angeles Times refuted and discredited the story, leading the San Jose Mercury News to withdraw it and sack Webb. After a stream of small jobs and financial ruin, Webb committed suicide.

A recent Hollywood movie, Kill the Messenger, reaffirms Webb’s findings. And at the talk I gave, many audience members, especially people of color who came of age during the heyday of the epidemic, expressed their firm belief that Webb was right, and that the CIA deliberately pushed crack cocaine into their neighborhoods with the express goal to destroy them. Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow gives credence to this “strong Webb theory” as well.

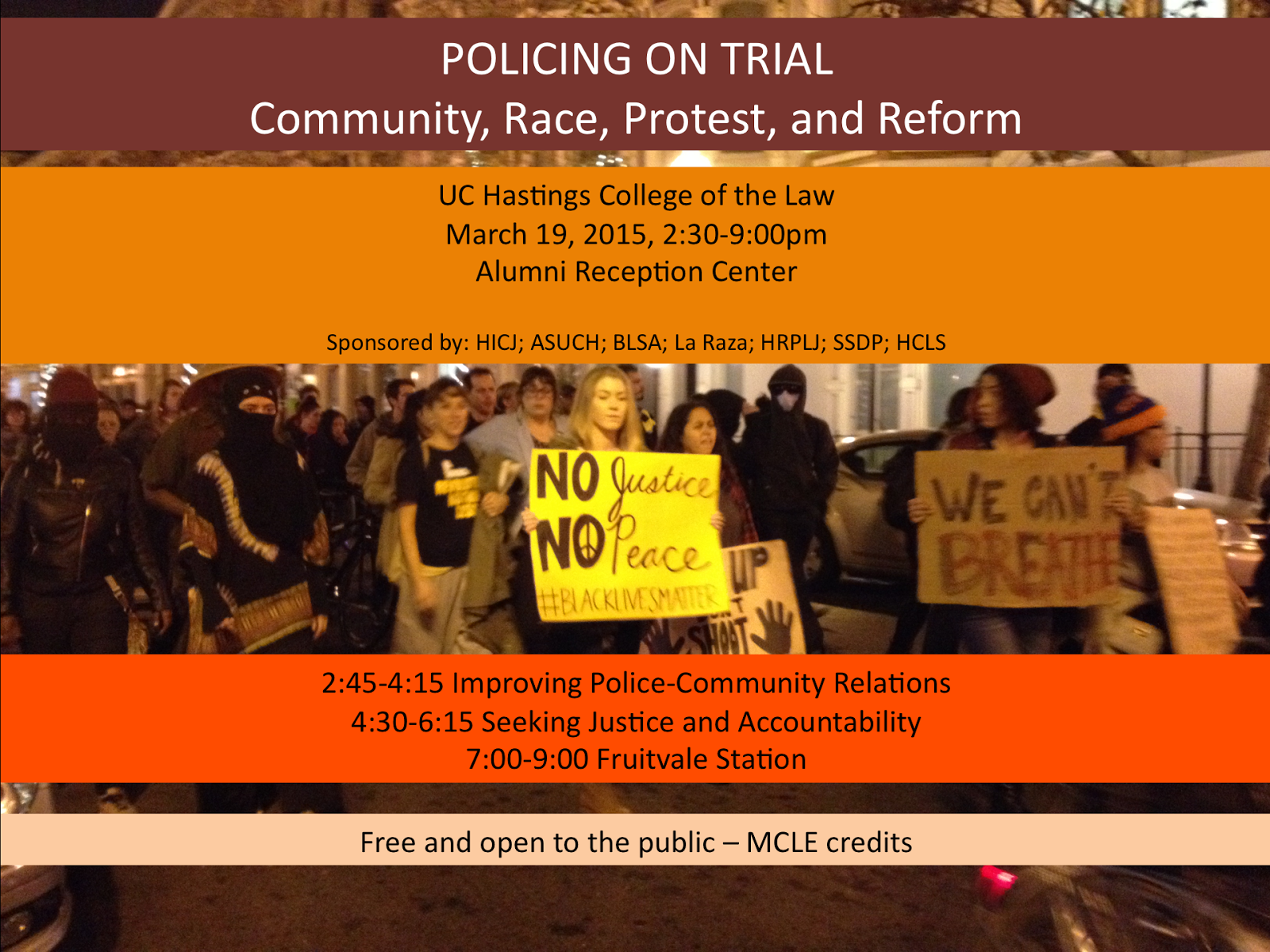

Which raises two questions: what do you believe, and, does it even matter what the truth is? When assessing our belief in a story, it’s important to keep in mind the context in which we hear it. There is a lot of talk about white privilege these days, and it’s making a lot of people angry and defensive to the point that I’m not sure the term is useful or productive anymore. What some hear as anger and some as accusation can, however, be understood as an effort to explain to others that one’s lived experience cannot inform a complete view of the subject, and that it is sometimes helpful to open one’s eyes and hearts to the lived experiences of others, particularly if one’s social advantages in life are taken for granted and make them unaware of lives lived without these advantages. The protests erupting in many American cities, by people who are sick of police abuse and of the devaluing of black lives, are an expression of this frustration with not being heard and with having a particular set of experiences ignored and trivialized, even when we are presented with irrefutable evidence.

I think it’s important to take these experiences seriously. Not because I think, at this point, that anyone can productively point the finger at someone at the CIA as some archvillain who decided that dying from crack would be white America’s “final solution” to the black population (if anyone did, I’m sure they’ve found that their cure was much worse than whatever disease they assumed to fix.) I think these experiences matter because, regardless of the personal intent of actors in the system, even if one assumes a modest version of Webb’s theories, which merely ascribes ignorance and neglect, it is frightening that the CIA’s rush to protect the Contras and their allies would lead them to discount the horrific effects drug importing would have on neighborhoods and communities.

In many ways–which I said on Sunday night at the show–ignorance and neglect are worse than intent and malicious design. Because, if someone is evil and malicious, we can point a finger, accuse, (try to) prosecute. But if there is an entire system which, at some point, just decided that the bottom 15% of American citizens are dispensable, there’s not a lot to do and the fight is going to be much longer and harder. And also, because anyone who regards you as an enemy at least ascribes you some importance. On the other hand, if you are discounted, disregarded, and discarded, it’s because, as many of the protesters today are pointing out, the system has come to the collective conclusion that your life doesn’t matter.

Another thought I’ve had on this has to do with the credibility of the theory. This morning, the Senate Committee’s report on the CIA’s use of torture came out. The report tells you what your country does to people, many of whom are probably innocent, without informing you (if you don’t know, please educate yourself). Before 9/11, before the nonexistent weapons of mass destruction, before many other things happened, some of you might’ve thought this impossible, a joke. But those of us who grew up on shows like Mission: Impossible were raised on the premise that we are the good guys, and as such, we are entitled to treat the world as our personal sandbox: torturing, abusing, stealing elections in at least eight countries. Mission: Impossible was a work of fiction, but maybe it was designed to make the inconceivable possible, to ameliorate our feelings and desensitize us for the moment in which we learned the truth.

And what a terrific indoctrination job! In 1974, when we found out that the White House was plotting to steal an election and spied on the opposite party, the president had to resign. Now, as we find out that a government agency is regularly listening to our telephone conversations and reading our mail, we’re not even apathetic; we’re jaded.

So the question is no more whether the crack cocaine conspiracy is believable or unbelievable. Pretty much everything is in the ballpark of the believable, and Webb’s exposé was not even that far from what the Senate itself admitted back in 1989. The question is, what are we going to do about this?