One of the problems of siloed reporting is that, in times of serious conflict, each side can remain isolated from news of suffering and horror on the other side. It’s understandable that parties to the horrific war in the Middle East can’t muster the attention, let alone the compassion, to read news from the “other side,” which explains why a San Francisco man telling of the slaughter of five family members by Hamas was met with jeers, horns, and pig noises, and why Matt Dorsey’s request that the sexual violence against Israeli women be similarly denounced yielded yells “liar” from my fellow San Franciscans. In my very institution, an educated, erudite, well-dressed man, a former colleague of many years, stood before an audience of 200 and ascribed facts of the massacre to “disinformation.”

But the problem goes both ways, and the Israeli press is not reporting on the humanitarian crisis in Gaza (nor is it easy for international orgs to do so). The Israeli’s public’s attention and capacity to feel for Gazans is pretty low. And, as Itamar Mann explains, if there’s anything good about the Hague tribunal taking place as I write, it is that it airs some of these realities, which we ignore at everyone’s peril.

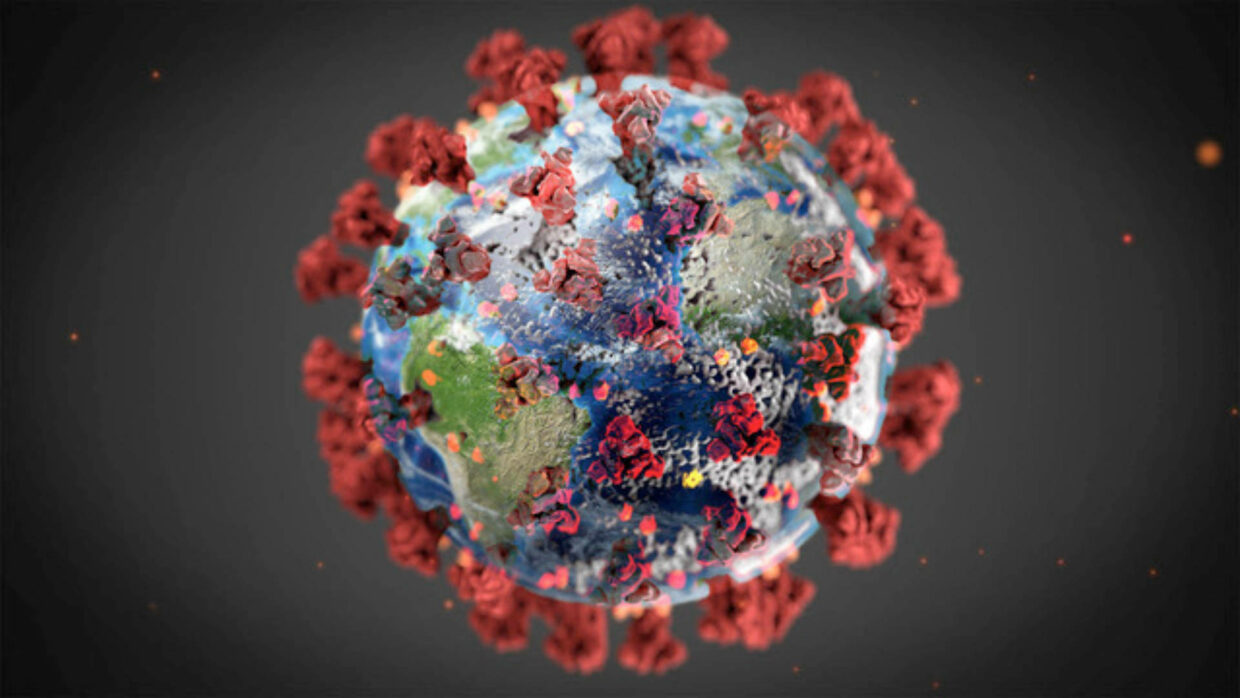

There’s one particular aspect to this disaster that we cannot and should not ignore, regardless of where one stand politically: the war is unearthing a serious public health crisis, including diseases. And as Chad Goerzen and I explain in our forthcoming book Fester, seeing disease through a siloed zero-sum game framework is a horrific mistake. Here’s NPR covering the WHO report about this public health crisis:

MARTÍNEZ: All right, wow, so really bad. How have things gotten so bad?

DANIEL: Well, Gaza’s health infrastructure has really crumbled amidst Israel’s bombardment and ground offensive. The WHO says more than half of Gaza’s hospitals are no longer functioning. And that’s because Israel has accused Hamas of harboring fighters and weapons in and around those hospitals and under them in tunnels, putting them in the line of fire [H.A.: this wording implies the accusations were not true; they were, of course]. Plus, the conditions inside Gaza are a perfect storm for the spread of infectious disease. There is intense overcrowding, colder winter weather and a lack of clean water, sanitation and proper nutrition, which are services that are difficult to secure under Israel’s near-total siege of Gaza. Here’s Amber Alayyan, deputy program manager for Doctors Without Borders in the Palestinian territories.

AMBER ALAYYAN: It’s just sort of a cauldron of possibility of infectious disease. This really just is an infectious disaster in waiting.

MARTÍNEZ: And that brings us back, I suppose, to the World Health Organization’s prediction that disease could endanger more lives than military action.

DANIEL: Exactly. And it’s why global health groups are racing to ramp up disease surveillance efforts.

Anyone getting sick and dying from a preventable disease in the shadow of conflict is a tragedy. There are heartbreaking reports of Gazan children suffering from horrendous diarrhea and infections. But when one is overwhelmed with grief and rage it’s hard to see that. What should not be hard to see, though, is that viruses and epidemics don’t take sides.

I’ve had plenty of opportunity to see the zero-sum game mentality in action. In Chapter 4 of Fester we recount the public debate about vaccination priority. You’ll be able to notice the same thinking error problem right away:

Advocates were trying to combat disturbing news: kowtowing to public pressure not to prioritize prisoners, CDPH removed prison populations from tier 1B of vaccination. This misguided zero-sum thinking—based, of course, on the myth of prison impermeability—reflected similarly worrisome developments nationwide. In Colorado, for example, the first draft of the vaccine distribution plan prioritized the prison population, but the governor later backtracked, “sa[ying] during a media briefing that prisoners would not get the vaccine before ‘free people.’” His response caused public uproar and was reported in national media outlets.

Similarly, in Wisconsin, parroting the old law-and-order playbook, assemblymember Mark Born tweeted, “The committee that advises @GovEvers and his department tasked with leading during this pandemic is recommend- ing allowing prisoners to receive the vaccine before 65 year old grandma?”

And, in Tennessee, health officials placed the state’s prison population last in line, because a state advisory panel tasked with vaccine prioritization, which acknowledged that prison populations were high-risk, concluded that prioritizing them could be a “public relations nightmare.” Documents reported that the panel understood the problem: “If we get hit hard in jails it affects the whole community. Disease leaves corrections facilities and reenters general society as inmates cycle out of their sentencing,” the document read, adding that when inmates get the disease, “it is the taxpayers that have to absorb the bill for treatment.” But while corrections workers were bumped up to one of the earliest slots, incarcerated people—including those who met the state’s age qualifications for earlier vaccinations—were relegated to the last eligible group.

I knew this was public health idiocy even as it was happening, and wrote an op-ed about that for the Chron. In addition to the heightened mortality and supbpar healthcare in prisons, there was another important consideration that should have led everyone, bleeding-heart liberals and hard-line law-and-order folks alike, to clamor for prison vaccines:

Second, prisons must be prioritized because vaccinating behind bars protects everyone in the state. It is imperative to understand the role that prison outbreaks play in the overall COVID picture of the state. As of today, all but two CDCR facilities have COVID-19 outbreaks, and numerous prisons have suffered serious outbreaks with hundreds of cases. Months of analysis I have conducted, superimposing the CDCR infection rates onto the infection in California counties at large, show correlations between pandemic spikes in prison and in the surrounding and neighboring counties. Vaccinating people behind bars protects not only them, but also you and yours.

The result was disastrous but predictable. In Chapter 5 of Fester we show how prison outbreaks impacted the overall COVID-19 picture in California. Our epidemiological analysis, which relies on the Bradford Hill criteria, included a counterfactual model in which the outbreaks in prison were controlled. The results were striking:

Together, these show that due to the extraordinarily high prevalence of COVID-19 cases inside CDCR facilities, particularly during the year 2020, these facilities had a large influence on their regions, far more than their rela- tively small population and isolation would suggest. Note the difference between the total casualties in Marin County with and without the counter- factual—58 deaths, 22 percent of the COVID-19 deaths in Marin for this period—and the difference between the total casualties in California with- out CDCR facilities—11,974 deaths, or 18.5 percent of the COVID-19 deaths in California for this period. Furthermore, the outbreaks in San Quentin and CDCR occurred before vaccinations were publicly available and before effective treatments for COVID-19 were developed, making them particularly high impact on mortality.

That’s close to 12,000 preventable deaths in the state of California–outside prisons–that are causally attributable to the outbreaks in prisons. We point this out because even people who can’t find compassion for their fellow Californians behind bars should wake up to the fact that, if the incarcerated population ails, all of us are put at risk.

Israeli newspaper coverage does not feature the dire epidemiological threat, because people’s attention is focused on the more direct existential risk from the war (especially with the possibility of a northern front becoming more and more real every day.) In the overall noise of political partisanship we could forget how densely populated the Middle East is, and how soldiers go in and out of Gaza. We also forget how easily epidemics travel the world and could quickly spread beyond the Middle East. I realize I’m speaking to a wall of partisanship, rage, and fear. I worry that the halt in the process of releasing hostages and prisoners is going to make this as much of a quickening sand situation as Lebanon was, and that eventually the public health outcomes will decide this conflict, to the detriment of everyone.

No comment yet, add your voice below!