Today I’m posting two dapim, because the entire unit on capital punishment is completed halfway through page 68, when a new conversation starts. The last outstanding issues on the subject of the four methods of executions have to do with criminal procedure in cases of incitement and with some wild, magical tales of sorcery. We’ll start with the former.

As opposed to other criminal trials, in which the Sanhedrin plays it straight, with inciters the mishna sets up special rules, which include undercover agents, entrapment, and eavesdropping (מַכְמִינִין). Because ordinarily a conviction requires two witnesses, the court faces a problem if the defendant only incited one person. In such a case, the person–an undercover agent–is supposed to say to the inciter, ״יֵשׁ לִי חֲבֵירִים רוֹצִים בְּכָךְ״ (“I have friends who might be into idolatry as well”), thus manufacturing more witnesses. But if the inciter is cumming (עָרוּם) and doesn’t fall for it, the witness takes him outside, while witnesses hide behind the fence, and tells the inciter: ״הֵיאַךְ נַנִּיחַ אֶת אֱלֹהֵינוּ שֶׁבַּשָּׁמַיִם וְנֵלֵךְ וְנַעֲבוֹד עֵצִים וַאֲבָנִים?״ (“how shall we leave our God in heaven and go worship trees and stones?”). If the inciter recants, הֲרֵי זֶה מוּטָב – that’s better – and if not, we now have evidence against him.

The gemara sets up different execution methods for different inciters: stoning for the ordinary person and strangulation for the prophet; while stoning is the punishment for inciting an individual, it is debated whether inciting a multitude is punishable by stoning or strangulation. Rav Pappa provides a variation on the mishnaic entrapment scheme for inciters: in his version, the entrapper sits with the inciter in a candlelit interior room, asking him to repeat his incitement, while the eavesdropping witnesses position themselves in an outer room so they can see and hear, but not be seen. Which leads the sages to a moment of reminiscing:

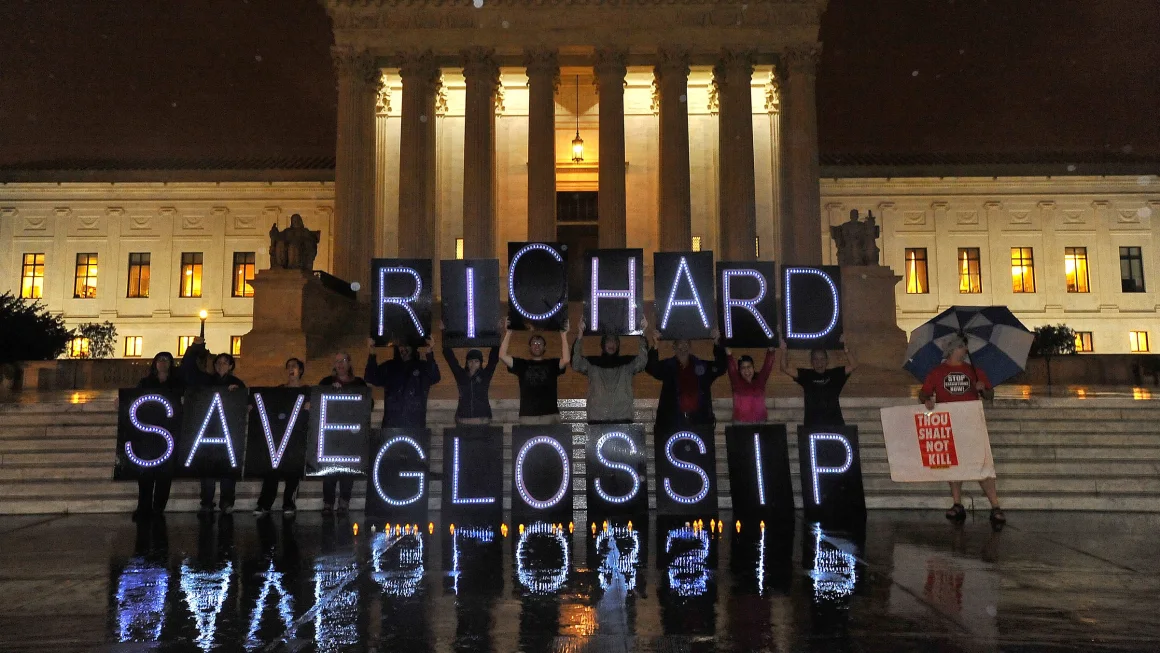

וְכֵן עָשׂוּ לְבֶן סָטָדָא בְּלוֹד, וּתְלָאוּהוּ בְּעֶרֶב הַפֶּסַח.בֶּן סָטָדָא? בֶּן פַּנְדִּירָא הוּא! אָמַר רַב חִסְדָּא: בַּעַל סָטָדָא, בּוֹעֵל פַּנְדִּירָא. בַּעַל? פַּפּוּס בֶּן יְהוּדָה הוּא! אֶלָּא, אִמּוֹ סָטָדָא. אִמּוֹ? מִרְיָם מְגַדְּלָא נְשַׁיָּא הֲוַאי! כִּדְאָמְרִי בְּפוּמְבְּדִיתָא: ״סְטָת דָּא מִבַּעְלַהּ״.

“You know,” says Rav Pappa, “the inner room entrapment thing, that’s what they did to Ben Setada in Lod, and they hanged him on Passover Eve.” “Ben Setada? You mean Ben Pandira!” Rav Hisda chimes in: “Nah, the mom’s husband was called Setada, but her lover’s name was Pandira.” “Husband?” someone else pipes up. “Her husband was Pappus ben Yehuda! It’s just the mom whose name was Setada.” “Nah,” someone hollers from the back pews, “the mom’s real name was Miriam Megadla, but because she cheated on her husband (סְטָת דָּא), they called her Setada (סָטָדָא).”

After this gossippy interlude, the sages shift gears by analogizing the inciter to another deceiver of crowds: a sorcerer who deceives the eyes. This round of law and story distinguishes between illusion magic–akin to stage magic–which is harmless entertainment, and actually making things happen in the real world. For example, standing in a field of zucchini (קִשּׁוּאִין) and performing a deceptive act as if one gathers them through sorcery is fine; actually using sorcery to gather the zucchini is prohibited.

We’ll get back to the zucchini magic in a little while. Meanwhile, we get a little sprinkle of misogyny: the biblical prohibition against sorcery encompasses both men and women, but uses the female form מְכַשֵּׁפָה. The reason? מִפְּנֵי שֶׁרוֹב נָשִׁים מְצוּיוֹת בִּכְשָׁפִים – because most women (!) have familiarity with witchcraft. The punishment for witchcraft, says Rabbi Yosei, is beheading by sword. His evidence is a similarity to a different verse containing the words לֹא תְחַיֶּה (you shall not suffer to live) which does involve execution by sword; Rabbi Akiva disagrees, saying that the witches must be stoned, and relying on a verse involving stoning that uses the words לֹא יִחְיֶה (none shall live). Then, they argue about the strength of the evidence. Rabbi Yosei says that the linguistic proximity he relies on is stronger. Rabbi Akiva retorts that the verse he relies on listed a series of deaths for Israelites (and singled out stoning for the offense with the similar wording), whereas Rabbi Yosei’s verse involved a verse regarding one form of deaths for gentiles.

Another argument about punishing sorcerers elucidates more legallogic. Ben Azzai sees two verses in proximity: one about witches and another about bestiality. Because the latter is to be stoned, he deduces the former is, too. But Rabbi Yehuda says that the proximity of the verses should not imply a similar idea–rather, witches (מְכַשְּׁפִים) should be treated like other offenders of the same category: necromancers (אוֹב) and sorcerers (יִדְּעוֹנִי). Because these last two are mentioned together, there is a debate (left unsolved) on whether they can be analogized to other cases or treated as a separate category.

Now we get some witchcraft nomenclature peppered with cool stories. Rabbi Hanina learned from Deuteronomy that a righteous person is immune to witchcraft. And, indeed, a woman was trying to collect dust from under Rabbi Hanina’s feet to put some hex on him, and he told her, “you shall not prevail.” While people in general should be wary of witchcraft, Rabbi Hanina is so righteous that he cannot be harmed.

There are some magic that is permitted–stuff that’s merely trickery. For example, on Shabbat, Rav Hanina and Rav Oshaya would study creation, and a third-born calf would appear, and they would eat it. This is apparently okay, as is the parlor trick that Karna’s dad used to do, in which he would blow his nose and create the illusion of rolls of silk streaming from his nostrils. But can witches and sorcerers actually create animals? Rabbi Eliezer thinks they cannot make tiny ones (and thus, the Egyptian sorcerers could not reproduce the plague of lice); Rav Pappa thinks they cannot create even camels, though they can move existing animals from place to place. Rav once saw a man kill a camel and then raise him from the dead with a drum, but Rabbi Hiyya, apparently less credulous, thinks it was an illusion because there was no blood or excrement at the site.

But wait! There’s more animal magic! Ze’eiri went to Alexandria and bought a donkey. But the minute the donkey’s lips touched the water Ze’eiri gave it to drink, he (the donkey, not Ze’eiri) turned into the plank of a bridge. Ze’eiri went complaining and asked for a refund, and the donkey dealership had the temerity to say, “if you weren’t such a fancy rabbi, we wouldn’t refund you. Who buys an animal these days without having it drink water first?” Caveat emptor, you guys.

Yannai also has a donkey story. He stayed at an inn and asked for a drink. When the innkeeper woman was serving him, Yannai noticed her lips were moving, so he said, “hey, I’m drinking from your glass; you drink from mine,” and performed sorcery on his own drink. The innkeeper took a sip and turned into a donkey, so Yannai mounted her and rode to the marketplace. On the way, the innkeeper’s friend came and released her from the spell, and so people saw Yannai riding to the marketplace on a woman.

Which is where we get to the zucchini business. The whole thing starts with a discussion of the plague of frogs. Since the original (Exodus 8:2) refers to “frog”, in singular, Rabbi El’azar says there was just one frog, who then spawned and filled the land with frogs. When Akiva presented this view, Rabi El’azar ben Azarya told him to stay out of aggadah, as it was not his field of expertise, and instead suggested that the one frog whistled to her friends, and that’s when they came and populated the land. Rabbi Akiva disputed this idea, repeating the aforementioned zucchini story from Rabbi Yehoshua (standing in a field of zucchini and performing a deceptive act as if one gathers them through sorcery is fine; actually using sorcery to gather the zucchini is prohibited).

This is a segue to Rabbi Akiva’s learning from Rabbi El’azar. Here’s the full story:

כְּשֶׁחָלָה רַבִּי אֱלִיעֶזֶר, נִכְנְסוּ רַבִּי עֲקִיבָא וַחֲבֵירָיו לְבַקְּרוֹ. הוּא יוֹשֵׁב בְּקִינוֹף שֶׁלּוֹ, וְהֵן יוֹשְׁבִין בִּטְרַקְלִין שֶׁלּוֹ. וְאוֹתוֹ הַיּוֹם עֶרֶב שַׁבָּת הָיָה, וְנִכְנַס הוּרְקָנוֹס בְּנוֹ לַחְלוֹץ תְּפִלָּיו. גָּעַר בּוֹ וְיָצָא בִּנְזִיפָה. אָמַר לָהֶן לַחֲבֵירָיו: כִּמְדוּמֶּה אֲנִי שֶׁדַּעְתּוֹ שֶׁל אַבָּא נִטְרְפָה. אָמַר לָהֶן: דַּעְתּוֹ וְדַעַת אִמּוֹ נִטְרְפָה! הֵיאַךְ מַנִּיחִין אִיסּוּר סְקִילָה וְעוֹסְקִין בְּאִיסּוּר שְׁבוּת? כֵּיוָן שֶׁרָאוּ חֲכָמִים שֶׁדַּעְתּוֹ מְיוּשֶּׁבֶת עָלָיו, נִכְנְסוּ וְיָשְׁבוּ לְפָנָיו מֵרָחוֹק אַרְבַּע אַמּוֹת. אָמַר לָהֶם: לָמָּה בָּאתֶם? אָמְרוּ לוֹ: לִלְמוֹד תּוֹרָה בָּאנוּ. אָמַר לָהֶם: וְעַד עַכְשָׁיו לָמָּה לֹא בָּאתֶם? אָמְרוּ לוֹ: לֹא הָיָה לָנוּ פְּנַאי. אָמַר לָהֶן: תָּמֵיהַּ אֲנִי אִם יָמוּתוּ מִיתַת עַצְמָן. אָמַר לוֹ רַבִּי עֲקִיבָא: שֶׁלִּי מַהוּ? אָמַר לוֹ: שֶׁלְּךָ קָשָׁה מִשֶּׁלָּהֶן. נָטַל שְׁתֵּי זְרוֹעוֹתָיו וְהִנִּיחָן עַל לִבּוֹ, אָמַר: אוֹי לָכֶם שְׁתֵּי זְרוֹעוֹתַיי, שֶׁהֵן כִּשְׁתֵּי סִפְרֵי תוֹרָה שֶׁנִּגְלָלִין! הַרְבֵּה תּוֹרָה לָמַדְתִּי, וְהַרְבֵּה תּוֹרָה לִימַּדְתִּי. הַרְבֵּה תּוֹרָה לָמַדְתִּי, וְלֹא חִסַּרְתִּי מֵרַבּוֹתַי אֲפִילּוּ כַּכֶּלֶב הַמְּלַקֵּק מִן הַיָּם. הַרְבֵּה תּוֹרָה לִימַּדְתִּי, וְלֹא חִסְּרוּנִי תַּלְמִידַי אֶלָּא כְּמִכְחוֹל בִּשְׁפוֹפֶרֶת. וְלֹא עוֹד, אֶלָּא שֶׁאֲנִי שׁוֹנֶה שְׁלֹשׁ מֵאוֹת הֲלָכוֹת בְּבַהֶרֶת עַזָּה, וְלֹא הָיָה אָדָם שׁוֹאֲלֵנִי בָּהֶן דָּבָר מֵעוֹלָם. וְלֹא עוֹד, אֶלָּא שֶׁאֲנִי שׁוֹנֶה שְׁלֹשׁ מֵאוֹת הֲלָכוֹת, וְאָמְרִי לַהּ: שְׁלֹשֶׁת אֲלָפִים הֲלָכוֹת, בִּנְטִיעַת קִשּׁוּאִין, וְלֹא הָיָה אָדָם שׁוֹאֲלֵנִי בָּהֶן דָּבָר מֵעוֹלָם, חוּץ מֵעֲקִיבָא בֶּן יוֹסֵף. פַּעַם אַחַת אֲנִי וָהוּא מְהַלְּכִין הָיִינוּ בַּדֶּרֶךְ, אָמַר לִי: רַבִּי, לַמְּדֵנִי בִּנְטִיעַת קִשּׁוּאִין. אָמַרְתִּי דָּבָר אֶחָד, נִתְמַלְּאָה כׇּל הַשָּׂדֶה קִשּׁוּאִין. אֲמַר לִי: רַבִּי, לִמַּדְתַּנִי נְטִיעָתָן, לַמְּדֵנִי עֲקִירָתָן. אָמַרְתִּי דָּבָר אֶחָד, נִתְקַבְּצוּ כּוּלָּן לְמָקוֹם אֶחָד. אָמְרוּ לוֹ: הַכַּדּוּר וְהָאִמּוּם וְהַקָּמֵיעַ וּצְרוֹר הַמַּרְגָּלִיּוֹת וּמִשְׁקוֹלֶת קְטַנָּה, מַהוּ? אָמַר לָהֶן: הֵן טְמֵאִין, וְטַהֲרָתָן בְּמָה שֶׁהֵן. מִנְעָל שֶׁעַל גַּבֵּי הָאִמּוּם, מַהוּ? אָמַר לָהֶן: הוּא טָהוֹר, וְיָצְאָה נִשְׁמָתוֹ בְּטׇהֳרָה. עָמַד רַבִּי יְהוֹשֻׁעַ עַל רַגְלָיו וְאָמַר: הוּתַּר הַנֶּדֶר, הוּתַּר הַנֶּדֶר! לְמוֹצָאֵי שַׁבָּת פָּגַע בּוֹ רַבִּי עֲקִיבָא בֵּין קֵסָרִי לְלוֹד. הָיָה מַכֶּה בִּבְשָׂרוֹ עַד שֶׁדָּמוֹ שׁוֹתֵת לָאָרֶץ. פָּתַח עָלָיו בְּשׁוּרָה וְאָמַר: אָבִי אָבִי רֶכֶב יִשְׂרָאֵל וּפָרָשָׁיו. הַרְבֵּה מָעוֹת יֵשׁ לִי וְאֵין לִי שׁוּלְחָנִי לְהַרְצוֹתָן.

Akiva and others came to see Rabbi Eliezer, who was sick, at home. The backstory to this tale is the famous story of tannuro shel achnai, in which the entire rabbi community stood against Rabbi Eliezer, even though he was right in pronouncing the law, and ostracized him (I’ll talk more about this story some other time). In any case, it appears that this visit was the first rapprochement after the ostracism. Rabbi Eliezer, obviously in a foul mood, first rebuked his son for wearing tefilin on Shabbat (a fairly minor offense), and then scolded his visitors for not having come to study first. He threatened them all with death, especially Akiva, and then berated them for not taking advantage of his Torah expertise – especially in matters of zucchini growing. The one exception, he says, was Akiva: “Once, Akiva and I were walking along the way and he asked to learn about planting zucchini. I said something, and the whole field filled with zucchini. He then asked to learn about uprooting them. I said something, and all the zucchini gathered in one place.” Eliezer then gave them one last purity law and died–and Rabbi Yehoshua proclaimed that the curse of his ostracism had been removed. At his funeral procession, Rabbi Akiva mourned him by striking his own flesh: “I have many coins and no money changer to give them to” (I have many questions, but my rabbi is gone and I have none who can answer them.” The anticlimactic coda to this heartbreaking story is that Eliezer was allowed to do zucchini magic because he just wanted to understand how the sorcerers do it, so he could teach it to others.

You guys, this marks the first complete sugiyah (issue, thematic unit) that we studied together beginning to end, and it was a tough one. Four Deaths deals with some difficult and even unpalatable issues, but we got some rules of criminal law and evidence out of it, some understanding of talmudic logic, and some disputes about severity scales.

הֲדַרַן עֲלָךְ אַרְבַּע מִיתוֹת

The second half of page 68 starts with a new issue: the complicated case of the rebellious son, which will keep us busy for a week or so. By way of introduction, let me explain the main concern of this sugiyah. The biblical anchoring for the entire conversation is Deuteronomy 21:18-21, which reads as follows:

כִּֽי־יִהְיֶ֣ה לְאִ֗ישׁ בֵּ֚ן סוֹרֵ֣ר וּמוֹרֶ֔ה אֵינֶ֣נּוּ שֹׁמֵ֔עַ בְּק֥וֹל אָבִ֖יו וּבְק֣וֹל אִמּ֑וֹ וְיִסְּר֣וּ אֹת֔וֹ וְלֹ֥א יִשְׁמַ֖ע אֲלֵיהֶֽם׃

וְתָ֥פְשׂוּ ב֖וֹ אָבִ֣יו וְאִמּ֑וֹ וְהוֹצִ֧יאוּ אֹת֛וֹ אֶל־זִקְנֵ֥י עִיר֖וֹ וְאֶל־שַׁ֥עַר מְקֹמֽוֹ׃

וְאָמְר֞וּ אֶל־זִקְנֵ֣י עִיר֗וֹ בְּנֵ֤נוּ זֶה֙ סוֹרֵ֣ר וּמֹרֶ֔ה אֵינֶ֥נּוּ שֹׁמֵ֖עַ בְּקֹלֵ֑נוּ זוֹלֵ֖ל וְסֹבֵֽא׃

וּ֠רְגָמֻ֠הוּ כׇּל־אַנְשֵׁ֨י עִיר֤וֹ בָֽאֲבָנִים֙ וָמֵ֔ת וּבִֽעַרְתָּ֥ הָרָ֖ע מִקִּרְבֶּ֑ךָ וְכׇל־יִשְׂרָאֵ֖ל יִשְׁמְע֥וּ וְיִרָֽאוּ׃ {ס}

This is a pretty unpalatable rule: a rebellious son, who does not listen to his parents even though they punish him, shall be taken by his parents out to the city gates. The parents shall complain to the elders that the son is disobedient and eats too much, and the whole city will proeed to stone the son to death in public. The rabbinical project, thus, is an effort to minimize the effect of this rule, define it as narrowly as possible, to the point that it is not enforceable.

This effort begins with the age of the son: they define it as someone who has just reached puberty (there’s a whole discussion of pubic hair) but not adulthood yet (defined by growing a beard): בֵּן הַסָּמוּךְ לִגְבוּרָתוֹ שֶׁל אִישׁ – a youth whose strength is close to that of an adult. Then, they argue that there are limitations on the father’s age: a minor cannot father a rebellious son, because the biblical text says ״כִּי יִהְיֶה בֵּן לְאִישׁ״ (a man, as opposed to a youth, shall have a son). We will see more exegetical effort to minimize the applications of the harsh biblical rule in the days to come.