Today and tomorrow’s pages address two issues on which there is plenty of writing in modern criminal law. The first is the issue of transferred intent. Usually, we look for a match between the physical elements (actus reus) of a criminal offense and the mental state (mens rea) required for committing it: we can’t find someone guilty unless we prove *both* beyond reasonable doubt. Murder offenses, then, require proof that A caused B’s death as well as proof that A intended to cause B’s death. The problem ensues when A intends to kill B but kills C, and the usual rule is that the intent transfers: since the law does not prefer B’s life to C’s, it’s the same to the law who A intended to kill, as long as they killed a person. But the mishna for today deals with scenarios in which the mismatch between intent and action is more profound: A intends either a lesser or a greater offense than the one he actually commits. In all these cases, the mishna says, A is not liable for the serious crime:

- A intended to kill someone for whom they would face a lesser punishment (e.g., intended to kill an animal and killed a person);

- A intended a non-lethal strike (say, at B’s hips) but made a lethal hit (say, at B’s heart);

- A intended a lethal strike, ended up making a non-lethal hit, but B died anyway (eggshell skull? a fluke?)

- A intended a non-lethal strike at B, an adult, but the blow landed on C, a minor (and thus more vulnerable), and killed him.

- A intended to lethally strike the minor, C, but mistakenly struck the adult, B, with a blow usually not hard enough to kill an adult, but B died anyway (eggshell skull? a fluke?)

So far so good. But the mishna implies that Rabbi Shimon disagrees, and the gemara elaborates:

רַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן אַהֵיָיא? אִילֵּימָא אַסֵּיפָא, ״רַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן פּוֹטֵר״ מִיבְּעֵי לֵיהּ! אֶלָּא אַרֵישָׁא: נִתְכַּוֵּון לַהֲרוֹג אֶת הַבְּהֵמָה וְהָרַג אֶת הָאָדָם, לַנׇּכְרִי וְהָרַג אֶת יִשְׂרָאֵל, לַנְּפָלִים וְהָרַג אֶת בֶּן קַיָּימָא – פָּטוּר. הָא נִתְכַּוֵּון לַהֲרוֹג אֶת זֶה וְהָרַג אֶת זֶה – חַיָּיב. רַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן אוֹמֵר: אֲפִילּוּ נִתְכַּוֵּין לַהֲרוֹג אֶת זֶה וְהָרַג אֶת זֶה – פָּטוּר. פְּשִׁיטָא! קָאֵי רְאוּבֵן וְשִׁמְעוֹן, וְאָמַר: ״אֲנָא לִרְאוּבֵן קָא מִיכַּוַּונָא, לְשִׁמְעוֹן לָא קָא מִיכַּוַּונָא״ – הַיְינוּ פְּלוּגְתַּיְיהוּ. אָמַר: ״לְחַד מִינַּיְיהוּ״ – מַאי? אִי נָמֵי, כְּסָבוּר רְאוּבֵן וְנִמְצָא שִׁמְעוֹן – מַאי? תָּא שְׁמַע, דְּתַנְיָא: רַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן אוֹמֵר, עַד שֶׁיֹּאמַר ״לִפְלוֹנִי אֲנִי מִתְכַּוֵּון״. מַאי טַעְמָא דְּרַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן? אָמַר קְרָא: ״וְאָרַב לוֹ וְקָם עָלָיו״, עַד שֶׁיִּתְכַּוֵּון לוֹ.

Essentially, and by contrast to the modern criminal law view on this, Rabbi Shimon (and, as is later explained, Rabbi Hizkiyah) would exempt *everyone* who committed a homicide with transferred intent; he finds a biblical anchoring from this position in Deuteronomy 19:11, which addresses a murderer lying in wait–presumably for a specific person. That the biblical text intends to hold the ambushing murderer liable implies that in cases where things went awry there is no liability.

The rabbis disagree. Instead, Rabbi Yannai’s school limits the interpretation of the Deuteronomy verse to situations in which A was ambushing a particular individual as opposed to throwing a stone into a crowd. But even here, there are variations: in the bible, the killing of a gentile is a less serious offense than the killing of an Israelite (lovely), and thus to some rabbis the percentage of Israelites and gentiles in the crowd matters (even lovelier). But if there is one gentile in the crowd of Israelites, he is “fixed”, and thus the treatment is as if there were half and half. In any case, the rule of lenity prevails: the doubt works in favor of the would-be murderer (all’s well that ends well, I suppose. Ugh.)

All these exemptions make it tough to explain away Exodus 21:22, which deals with a situation in which brawling people who hurt a pregnant woman and kill the fetus are liable; the rabbis explain that the liability in such a case is expressed through money damages, not through execution. But the school of Rabbi Hizkiyah disagrees: they believe that the verse refers not to situations of accidental killings, but to situations of transferred intent, and therefore agree with Rabbi Shimon that there is no liability here at all.

***

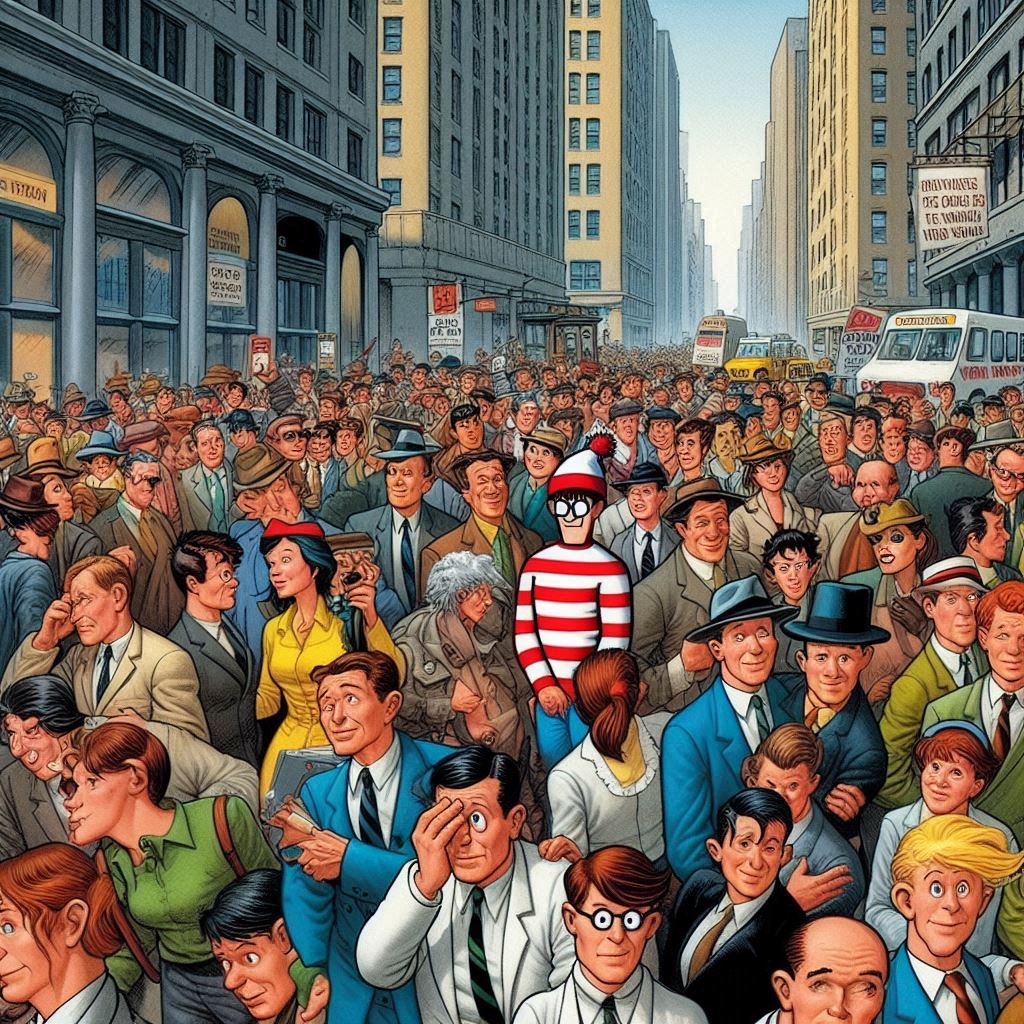

This discussion of the rule of lenity connects us to the second issue that comes up in these pages: a mishna involving a murderer who hid himself in a crowd, the sinister version of Where’s Waldo. Since the killer cannot be identified, all must be acquitted (reasonable doubt). Except, Rabbi Yehuda believes that all of these people, including the unidentified guilty party must be taken to a place called a כִּיפָּה (a room with a dome?), and at least according to one translation, they will all die in that room (this is intractable logic and will be discussed in detail in a little bit). Similarly, people sentenced to a variety of deaths who mix together, making it impossible to match a person to their execution method, must all be killed in the most lenient form–except, as you’ll recall from our earlier pages, there is a debate over which is the more lenient form. The previous discussion did not quell this debate, which now reignites, but we won’t go there. Instead, we go on to try and understand the logic of the Where’s Waldo mishna–particularly Rabbi Yehuda’s bizarre suggestion that the whole crowd is to die in the domed room–with the help of three perspectives:

- Rabbi Abahu cites Shmuel, who explains away the confusion by relating the mishna to a situation in which a murder defendant whose case has not yet concluded in a decision mixes up with a crowd of convicted murderers. While the majority opinion is that the person cannot be judged in absentia, and thus cannot be executed along with the convicts, Rabbi Yehuda presumably feels uncofmortable because the rest of the crowd is guilty.

- Resh Lakish thinks that everyone, including Rabbi Yehuda, would agree that no one should be executed in the Where’s Waldo scenario; however, Rabbi Yehuda’s ruling applies to a goring ox whose verdict has not yet been given and who is hiding amidst a whole herd of convicted goring oxen.

- Rava points out the difficulty of reconciling this position with the possibility that one of the sages’ fathers might be in the crowd. Rather, he says, the mishna refers to a scenario in which two people stand next to each other, and an arrow emerges from the two of them and kills a person; neither is liable, as we do not know who shot the arrow (the causation analysis in this situation would be a lot more complicated in modern law).

From here, the sages draw an analogy to goring cows who give birth to calves, which I personally do not find all that helpful or savory. So instead let’s take a look at one final little pearl. In the argument about which execution method is more severe, we’re told that Rav Yehezkel and his son, Rabbi Yehuda, disagree. The son says to the father (presumably in public): אַבָּא, לָא תַּיתְנְיֵיהּ הָכִי (“Dad, don’t teach it this way.”) This rudeness draws a rebuke from Shmuel:

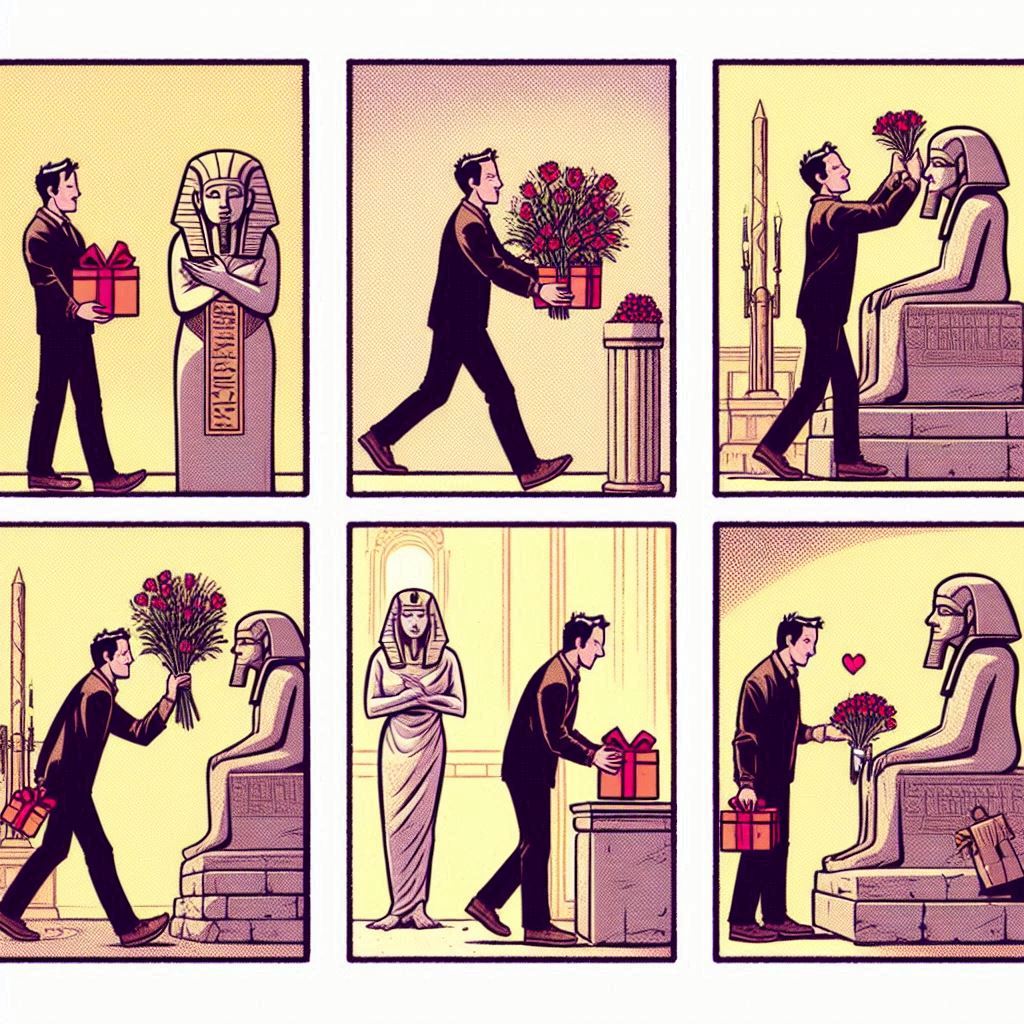

אֲמַר לֵיהּ שְׁמוּאֵל לְרַב יְהוּדָה: שִׁינָּנָא, לָא תֵּימָא לֵיהּ לַאֲבוּךְ הָכִי, דְּתַנְיָא: הֲרֵי שֶׁהָיָה אָבִיו עוֹבֵר עַל דִּבְרֵי תוֹרָה, לֹא יֹאמַר לוֹ: ״אַבָּא, עָבַרְתָּ עַל דִּבְרֵי תוֹרָה״, אֶלָּא אוֹמֵר לוֹ: ״אַבָּא, כָּךְ כְּתִיב בַּתּוֹרָה״. סוֹף סוֹף הַיְינוּ הָךְ! אֶלָּא אוֹמֵר לוֹ: ״אַבָּא, מִקְרָא כָּתוּב בַּתּוֹרָה כָּךְ הוּא״.

Shmuel says, “Oi, long-toothed one, don’t talk to your dad that way. A baraita says that, if a son sees his dad violate the Torah, he must not say, ‘Dad, you violated the Torah,’ but rather indirectly point out, ‘Dad, the Torah says x.'” Other sages disagree with Shmuel – both formulations are rude, and instead it’s best to say to your dad something even more oblique, like, “Dad, this verse says x.’

We resume on Saturday with page 81.