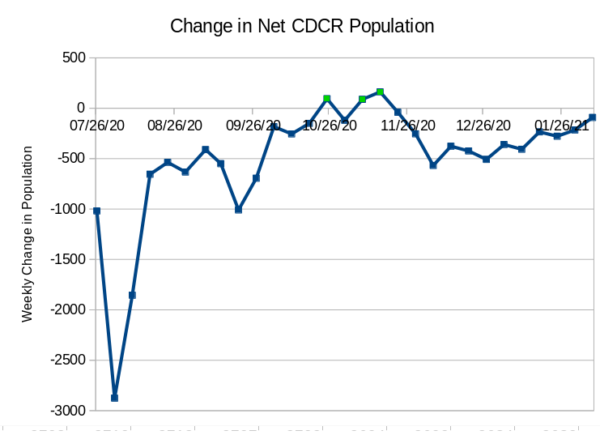

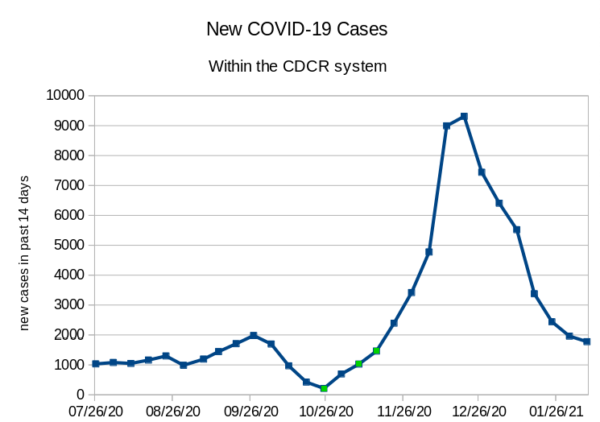

Today, Judge Tigar held a two-hour case management conference in Plata v. Newsom to discuss the latest developments as described in the joint case management statement. On the agenda were specific issues such as vaccination plan and staff compliance, but in the background loomed the basic problem: the solution to this catastrophe is a mass release but none is forthcoming.

The conference opened with CCHCS Receiver Clark Kelso offering an overview of the vaccination progress and plans. So far, in skilled nursing facilities, they have vaccinated 2300 incarcerated people. In combination with people who recently had COVID, they are approaching 80 percent coverage in these institutions. The good news are that the refusal rate is very low–between 8 and 10 percent–especially compared to previous vaccination campaigns such as flu vaccines. In response to Judge Tigar’s question, Mr. Kelson explained that they will have a full documentation of the refusals.

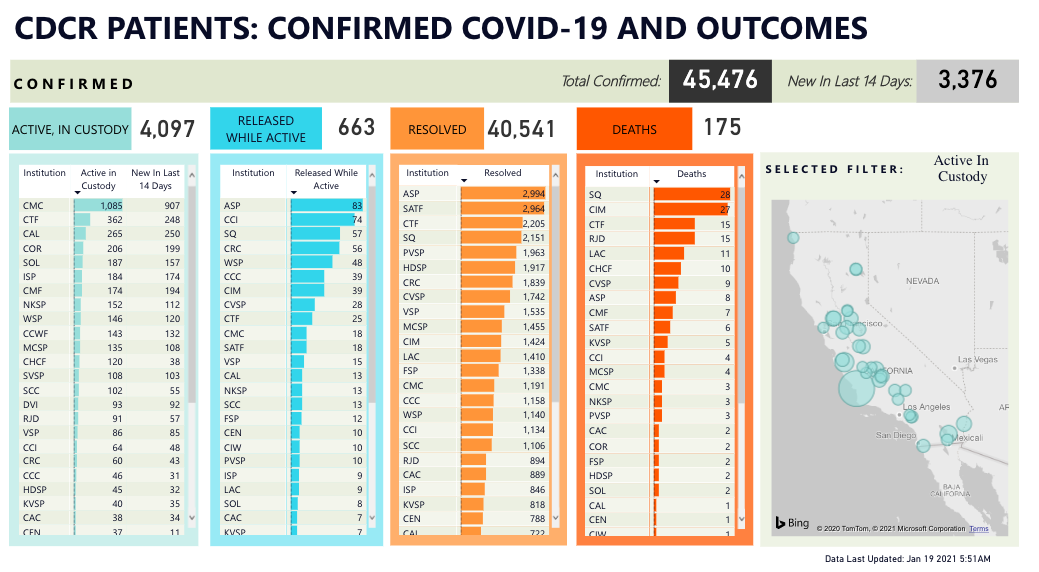

Judge Tigar’s next questions were an effort to find out how far CDCR/CCHCS were from vaccinating the entire COVID-naive population behind bars, assuming that appropriate vaccine dosage would be available. Kelso explained that the next step is to offer the vaccine to everyone aged 65 and up (2000 people, if you exclude people who have been infected.) After that, the next priority would be people who have not been infected with COVID and have risk scores of 3 and above (CCHCS uses a scale based on CDC risk assessment, where they assign points to preexisting conditions.) Kelso estimated that this group–approximately 5200 people–could be vaccinated in about 7 days. The next scenario would be to tackle 42,000 people–the remaining people in CDCR custody who have not been infected–which would realistically take about 4 weeks. The severe nursing shortage was mentioned, of course.

The problem, as I explained in a previous post, is not buy-in from incarcerated people but from staff. Kelso explained that, so far, they have vaccinated 19,351 staff members, out of which 110 have received the second dose. In the three skilled nursing facilities, staff buy-in is 95% and full vaccination will be completed in a few days. The percentage of compliance among the staff is declining, and even though no one at the hearing provided a breakdown, it was widely assumed (probably with good reason) that the problem is with custody staff rather than with health care professionals.

At that point, Judge Tigar talked about the elephant in the room: the institutional unwillingness to take the obvious best step, which would be releases. “I have sometimes become emotional when discussing this,” he said, referencing the previous hearing, in which he mentioned people who died by name and showed their pictures. He said that he “cajoled and begged the governor to release significant numbers beyond the current numbers so we can avoid unnecessary sickness and death. So far these requests have, again, with all appreciation for the efforts that have been made, fallen on deaf ears. The consequence is now becoming more apparent. COVID has spread more easily than it had to, and we’ll never know for sure, but there is unknown number of people who got sick and died who didn’t have to.” Judge Tigar highlighted the importance of granting people the good time credits they are unable to earn because of the lockdowns, saying that “we’re overincarcerating and doing worse precisely when we were supposed to do later.” He also pointed out that he “[could not] overemphasize the need to release elderly infirm people. There is an alarming increase in deaths” (56 since the previous case management conference) and “we must ensure it does not continue. I take this case personally. I asked CDCR to send me the records of all the inmates from CMF and CHCF who died from COVID since the last CMC. The vast majority were elderly.” Judge Tigar was visibly emotional when describing incarcerated people who have to use commode chairs when going to the bathroom–and “when the virus came, they were defenseless, and they died.”

Judge Tigar then pressed CDCR counsel Paul Mello on whether the “primary reason” for the alarming infection rates was people’s refusal to move to safer housing. Mello replied that “in some instances people aren’t moved quickly enough but [refusal] appears to be the primary reason.” Judge Tigar urged to increase education, so that people “may appreciate the efforts being made to protect them.” This, again, led to the discussion of the thorny problem of the staff: refusals to wear masks and get tested. Judge Tigar probed as to what the reasons might be, getting very little input from the parties (here on the blog, I’ve looked into the twisted priorities of CCPOA, as well as at the possibility that the rank-and-file, like the rank-and-file of other law enforcement orgs, is a hotbed of Trumpist COVID denialism. I have searched high and low for surveys of correctional officers’ political opinions and found none.)

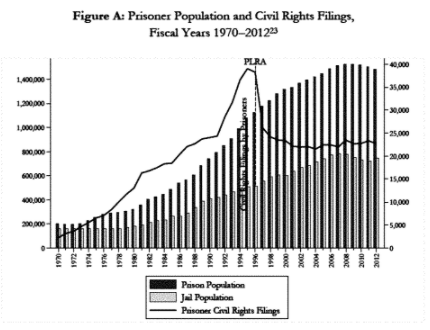

Even in the face of all this, Judge Tigar insisted that he is not yet at the point at which the PLRA enables him to release people pursuant to a finding of “deliberate indifference.” “if I could let people out I would do it today,” he said, but ” my view of the law is that I’m not allowed to do that.” The plaintiffs, of course, disagree, but Tigar seems very convinced that, legally speaking, his hands are tied, which he says is a “source of incredible frustration” to him. While he is not ruling out a future finding of deliberate indifference, he says, “we’re not there yet.”

While listening to the hearing, I was trying to ponder what was behind this sense Judge Tigar had that his hands are tied. Partly, it seems to stem from his reading of the PLRA, and partly from what seems to be his judicial psychology of this case, according to which “litigation is a very bad way to resolve this… communication is the right way.” A case in point was his effort to get to the bottom of the staff noncompliance. Tigar made an effort to get everyone on board: “Everyone doesn’t like low staff testing rates. We need to get them as high as possible. Why are they where they are to begin with?”

At this point, he turned to the CCPOA representatives, the union lawyer David Sanders and labor attorney Gregg Adam, in an effort to get the union’s collaboration at “[a] moment when CCPOA can become an invaluable partner if they want to, to keep their brothers and sisters safe.” This opportune moment, in my opinion, was ten months ago, but okay. Judge Tigar hammered home the need to get complete buy-in from the leadership: “If the captain says you have to wear a mask, then you have to wear a mask, no exceptions. If that becomes policy, that is how this is going to work.” The back-and-forth between the judge and union counsel offered another insight into Judge Tigar’s cooperative psychology: he told them that the benefit would be that compliance orders from above “create[s] an environment where you can publicly take the position that you don’t like masks but I wear one because I have to, because I don’t have a choice. If leadership is uniform, it creates a position where it is much easier for staff to be uniform. Consistent, off the job too. I’ve been hoping that CDCR/CCHCS would create videos for staff using staff. I asked and asked and asked more than you will ever know. Then I gave up. Then they did it and they’re great, I just saw them yesterday. Your staff will see them. And they make this point. You can’t be in the car with your friends driving to work or going to someone’s backyard thinking, I know these guys. COVID doesn’t care who your friends are. Need to wear is the same, on and off. On that level. [high command gives] order to do on job, expect[s] [compliance] off job, do it myself.”

One of Judge Tigar’s ideas was to solicit a volunteer in each prison who is “down with the goal” to report to a member of Kelso’s staff who “comes from custody and speaks the language.” He also seemed to set a lot of store by Prof. Amy Lerman of the Goldman School, regarding correctional culture and fostering compliance (this is good news, because insights into correctional culture is what we need.) Happily, Adam, one of the CCPOA representatives, also seemed to have respect for Lerman and also mentioned that they were planning to speak to Prof. Elizabeth Linos (whom Tigar referred to as the “persuasion guru” about compliance strategy. At that point, CCPOA counsel Sanders offered what seemed to me a very partial and revisionist history of CCPOA’s involvement in this issue, presenting CCPOA as the great champions of the original Plata release order, both because of the safety of their own employees and because they apparently thought that it was “morally and professionally wrong, what happened in our prisons – warehousing human beings and literally seeing them die because of conditions.” None of this explains why CCPOA, in the same breath, invested 4 million dollars in punitive propositions just in the last elections, while their own members were dying of COVID, or why they are suddenly in a rush to jaunt to Vegas amidst all this, but okay. Another thing we learned from Sanders is that Tigar’s exhortation to model good conduct would likely go nowhere because “we don’t represent captains” and because “sergeants and lieutenants don’t have collective bargaining power.”

At this point, when the conversation turned to isolation and quarantine, the hearing again touched on the heart of the matter. In the previous status conference, the plaintiffs asked that CDCR comply with the Receiver’s directives, but as infections and deaths soared, they changed tacks and asked that CDCR procure vaccinations for everyone. Mello’s reaction to this request was to resort to legalese: not only did they get the request too late, he said, “we think an order will be unnecessary and will constitute undue intrusion on authority.” There are also practical hurdles, he explained, and CDCR was not out of line by addressing this within the confines of current CDC health directives. Getting back to the PLRA hurdle, Mello opined that the plaintiffs face an uphill battle showing deliberate indifference with expert testimony.

While Tigar did not lose his temper–and seemingly agreed with Mello about the legal point–he clearly found the resort to legalese somewhat tasteless. “I think about this in a simplistic way,” he said, “I heard Mr. Kelso say that he needs 40,000 doses to get the job done. Two and a half million doses have already rolled in to the state. 40,000 is couch cushion money. Do we think that the governor can shake 40,000 doses loose? We can litigate this, and by the time the litigation will be resolved, this will be a dead issue. There are things I can do to expedite matters, but I have a much simpler question. Do we think the governor could shake loose whatever the number is, 40,000 doses to protect the population that he has already recognized is defenseless, deeply in need of this vaccination, and because of the role of prison [in the larger infection story] greatly affect public health in a positive way? Do you think he would shake them loose if I asked him to?”

Sara Norman of the Prison Law Office responded with a moral call to action. “This is not litigation about vaccination,” she explained, “it’s about quarantine, hundreds of thousands quarantined with shared air, which has resulted in significant illness and death.” The solution, she said, “has been obvious”; releasing people “is their choice and they have continued to place our clieets, their patients, at significant risk of harm. . . We are now saying there’s another solution.” Vaccination of incarcerated people–mandated by virtue of their classification as 1.B.2. in the priority list–is “within [CDCR’s] reach, they can do it.” Norman ended by quoting Yoda: “Do or do not, there is no try. It is up to them to do it.”

I’m left with a lot of questions. First, when will someone tackle the elephant in the room–Trumpist COVID denialism among the staff? Second, is “shaking loose” 40,000 doses a mere issue of friendly persuasion of the Governor? Most importantly, if all the horrors of the last ten months have not persuaded Judge Tigar that the PLRA’s deliberate indifference standard has been met, what is it going to take?