As I was preparing to teach the first Fourth Amendment class, I got an email from our appellate advocacy team: would I be willing to be on a panel about Idaho v. Dorff, an Idaho Supreme Court case that has been granted cert by SCOTUS recently? I read the whole decision – you can do the same here at this link – and honestly, I’m not sure how much of a big deal this is. Here’s the back story:

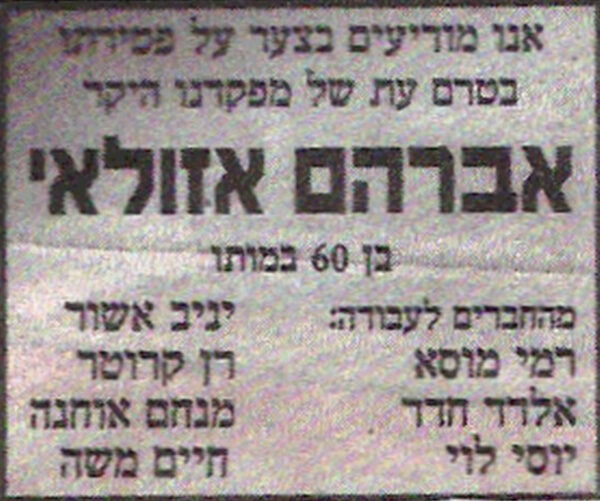

On a night in August 2019, a patrol officer from the Mountain Home Police Department initiated a traffic stop on a vehicle. The patrol officer reported witnessing the driver “make an improper turn,” “cross three lanes of traffic and then fail to use [his] turn signal.” Two men were in the vehicle: Kirby Dorff, the driver, and Mitchell Hall, a passenger. After the patrol officer stopped the vehicle in a grocery store parking lot, Dorff told the officer that he did not have a valid driver’s license or proof of insurance in the vehicle. During the time the patrol officer was speaking with Dorff and Hall, a K-9 officer arrived on scene with his drug dog, Nero.

The K-9 officer circled Dorff’s vehicle twice with Nero. Nero never entered the interior compartment of the vehicle.However, as Nero circled the vehicle, Nero directed his nose close to the vehicle’s seams (nearly touching the vehicle in many instances); entered the wheel well areas with his snout; and reached for the vehicle’s undercarriage with the same. On Nero’s second pass, body-camera footage from the on-scene officers shows Nero made two potential contacts, and one explicit contact, with the vehicle’s exterior surface: first, on the rear passenger side of the vehicle (briefly as he jumped up); second, on the front passenger side of the vehicle (again, briefly as he jumped up); and third, on the front driver side of the vehicle—this time planting his front paws to stand up on the door and window as he sniffed the vehicle’s upper seams. During this time, the K-9 officer made upward gestures, purportedly “[p]resenting areas for [Nero] to sniff.”The K-9 officer later testified that Nero alerted during his explicit contact with Dorff’s vehicle, i.e., after Nero stood up and put his front paws on the front driver side door and window.

Following Nero’s alert, on-scene police officers searched Dorff’s vehicle.In it, they found a pill bottle, folded papers, and a baggie—all containing white residue that later tested positive for methamphetamine.The officers also found “[a] purple container filled with a green leafy residue” in the trunk.

This led them to more searches and more evidence, all of which would fall apart if the initial search was unreasonable. Which, of course, Dorff claims it was. Here’s the footage from the search – you be the judge:

Fourth Amendment enthusiasts in the crowd may recall that, in 1967, the Warren Court replaced the trespass test with a subjective-objective privacy test: police action is a “search” or a “seizure” if it violates the target’s reasonable expectation of privacy. Anyone seeking to suppress evidence has to show that they had a subjective expectation of privacy in the premises/effects, and the court must find that it’s an expectation society accepts as reasonable. But in 2012, the Roberts Court held that they had never completely abandoned the trespass doctrine. Following up on this logic, the Idaho Supreme Court digs deep into 18th century British Law (I read 20 pages of Blackstone blathering so that you don’t have to) and found that the touching of the car with the dog’s paws is “intermingling,” which constitutes trespass to chattel, and is thus a “search.” Okay.

I have two thoughts about this. The first one is that, watching the videos, I think one could make a plausible case that the dog-on-car-door action in this case was a search even under the reasonable expectation of privacy test. The video is truly worth a thousand words. First of all, not to put too fine a point on it, Nero is a big-ass dog. It reminds me of Dr. Mortimer’s immortal words: “Mr. Holmes, they were the footprints of a gigantic hound!” And Nero was leaning on the window for a good six seconds, wasn’t he? That’s clearly visible in Exhibit B. I think the extent to which this was a menacing, intrusive situation can be sensitive to the size of the dog and to the length of the intrusion. Seeing Nero slobber in my car window would definitely make me feel like some boundary between me and the world has been intruded.

The second thought has to do with Nero’s handler, who seems to be motioning upwards and even, if I’m not mistaken, saying “up” at some point. This is related to my general disgruntlement about how our exploitation of animals extends law enforcement activities. The Fourth Amendment applies only to state action, which raises the question – what is Nero, exactly? A cop? An instrument of a cop? A civilian police employee or volunteer? Some animal rights theorists are pursuing animal personhood in the form of labor rights for police dogs. Is the determining factor whether Nero is his own agent, or following his handler’s command? Or is the extent to which his whole life revolves around being useful to humans in detecting drugs determinative in making anything he does into state action, regardless of whether he is responding to a command at that particular moment?

I talked about this with some eminent Fourth Amendment eggheads, who do not think this case will be a big deal in the long run. First of all, the Supreme Court granted cert but will likely not reverse and it just not that interested in Fourth Amendment issues. And second, this case can easily be limited to its facts. I’m not so sure. Consider the fact that the Golden State Killer was caught, in part, through removing DNA from the exterior of his car. Would that behavior now require a warrant? Does this mean we now treat every vehicle–not just vehicles located in the home’s driveway–as a protected constitutional zone?