–>

The case was not unlike hundreds of others in the Israeli army: a soldier, 18 or 19 years old, left his unit to go home and work for a couple of months, and was charged with absence without leave. His lawyer, a military public defender, reached out to his relatives and their caseworker and gathered a large amount of documents attesting to the family’s poor conditions: a mother with five or six kids living in abject poverty, their utilities cut off for lack of payment. The defendant insisted on testifying and portrayed a distressing (and true) picture of misery and squalor.

Then, the military prosecutor cross-examined the defendant. It turned out that one of his brothers had turned 13, and that the trigger for the absence was the need to finance the brother’s bar mitzvah. Which the family celebrated at a fancy party hall, with a thousand invitees, and new festive outfits, haircuts, and makeup for the family.

The judges were horrified by what they considered a warped sense of priorities. The defense attorney, thrust into a position of cultural translator, tried to rely on multiculturalism but was plagued by the uncomfortable feeling that the judges thought of her as the Jane Goodall of poor defendants from disadvantaged backgrounds, charged with explaining that “this is how ‘they’ are”. She felt that something was very wrong, and that there were ethnic undertones to the situation, but could not pinpoint exactly what was going on.

The defense attorney was me, and the discomfort plagued me throughout my military service and later in my academic career. Haunted by the experience of the judges hectoring the defendant (and many other discomfiting situations I encountered in practice) I devoted my

doctoral dissertation to the study of conscientious objectors and deserters (

here are my main findings.) The point of departure was that both groups challenged the Israeli military service ethos, under which everyone must serve in the army (this is largely a fiction), but did so from positions on the Israeli socioeconomic ladder: the objectors were members of the Israeli intelligentsia, sons and daughters of academics and journalists, refusing to serve in the army for ideological reasons, and the deserters belonged to disadvantaged and underserved sectors in Israeli society: Mizrachi Jews, immigrants from the former USSR and from Ethiopia, Druze and Bedouians. I found that the two groups posed very different types of threats to the military service ethos, and while both ended up convicted and incarcerated, they were treated quite differently by the authorities: the conscientious objectors were subjected to intellectual sparring aimed at securing the legitimacy of the army’s position, whereas the deserters–by far a larger group–were trivialized and handled via an assembly line of

“normal crimes” and almost automatic sentencing. Worse, because of the technicalities of military charges, the deserters–but not the conscientious objectors–were saddled with a criminal record that followed them to civilian life.

In the course of trying to figure out how the system perceived, framed, and treated young people committing AWOLs, I ran a large-scale regression model, controlling for both legal and extralegal variables. I found that the best predictor of sentence length, to a point, was the soldier’s length of absence for service, which turns out to be a rather arbitrary number, dependent upon the work schedule of the military police officers charged with apprehending deserters. My extralegal variables included the characteristics of the offender.

Among other things, I wanted to measure whether Mizrachi defendants were treated differently than Ashkenazi defendants, but I hit an obvious snag: there is no easy way to distinguish Mizrachim from Ashkenazim. In the absence of a better solution, I coded the defendants’ ethnicities using last names–

an imperfect indicator, given intermarriage and ethnically-neutral Hebrew versions of foreign names. Mizrachi origins did not come out significant in influencing sentencing. But I did observe that, between Mizrachi, Russian, Ethiopian, and Druze defendants, there were fairly few Ashkenazim.

This observation was, in itself, problematic, and hit a fertile Petri dish of theoretical and substantive difficulties. As Yifat Bitton

writes, the Mizrachi category is invisible in Israeli law, which gives the establishment plausible deniability of any problem. This invisibility is part and parcel of the criminal justice bureaucracy, which does not code the ethnicity of Jewish suspects and defendants at any step of the criminal process–from complaint to sentencing. Nevertheless, there is a persistent stereotype associating Mizrachim with crime. In a study by Arye Rattner, et al., respondents were presented with photographs of people with Ashkenazi, Mizrachi, and Arab appearances, told that these were photographs of criminals, and invited to offer guesses about their crime. The respondents associated more criminality with the Mizrachi and Arab photographs; they also tended to identify Ashkenazim with white collar crime and Mizrachim with street crime. These tendencies are on par with a rich array of popular culture artifacts supporting the Mizrachi-criminality nexus and the idea that Mizrachim “have trouble with the police.” From

Salakh Shabbati through the Gashash skit

Offside Story to the Yehuda Barkan

Aba Ganoov movies, Ashkenazi figures are associated with the law enforcement/social services complex–as judges, lawyers, and psychologists–whereas Mizrachi figures, even when portrayed as positive, warm, down-to-earth characters, are often associated with legal trouble and criminality (these popular movies, as

Ella Shochat explains, tend to be self-aware and reflexive.) This association is also bolstered by Israeli true crime classics, such as those written by Sarah Angel and Yitzhak Drory, which draw heavily on ethnic themes. An exception was Jack Cohen’s portrayal of a police officer in Skhunat Haim, but he portrayed a kind, friendly community police officer in a largely Mizrachi community. Even later depictions of Mizrachim as part of law enforcement, such as in

Batya Gur’s Michael Ohayon series or

Dror Mishani’s The Missing File, do not portray Mizrachim in positions of power and, when they defy stereotypes, do so in an aware way. A self-aware return to these stereotypes can be found in

Kobi Oz’s book Moshe Chuato and the Crow (Oz’s work is rich in critical examination of the Mizrachi-crime stereotype.)

Three questions arise from the presence of these stereotypes:

- Is the perception that Mizrachim are overrepresented in Israel’s criminal justice system real?

- If, indeed, Mizrachim are overrepresented, what does it mean? Are there insights here on criminality, criminalization, or both?

- How can we measure discrimination in the absence of recording categories?

Starting with the first question, measuring overrepresentation is not easy. Israeli bureaucracy, as Bitton explains, does not track Mizrachi identity, and the only possible tracker for panel data–last names–can be misleading in light of intermarriages and the proliferation of “Hebrewcized” names, which is common among both Ashkenazim and Mizrachim. Coding one’s own data from courtroom observations can also be complicated, as physical appearances can be misleading. What’s left is imputing the defendant’s ethnicity from the characteristics of the case. Building on David Sudnow’s idea of “normal crimes”, according to which legal actors develop a quasi-sociological taxonomy of the common ways in which crime is committed, experienced professionals might already have notions of crimes typically committed by Ashkenazim and Mizrachim. Of course, relying on this indicator reproduces exactly the kind of biases that one is trying to detect, and is therefore a poor solution as well as a compounding factor.

If these problems seem intractable, it’s important to keep in mind that a system that tracks ethnicities is not necessarily better. Think about two obvious comparators: the U.S. system, which thoroughly (and arguably obsessively) tracks Black identity and the Israeli system, which tracks Arabs with at least as much persistence.

The U.S. system tracks race at every junction. For a category that is presumably a social construct, with no ontological existence, it sure follows the determinations of whoever arrests you; from suspect descriptions, through arrest booking data, through prosecutorial decisionmaking, to trial and sentencing, the distinction black/white is officially recorded throughout the process. Not only that–there’s pressure to track even more: the upshot of

Floyd v. City of New York (2012) was that NYPD officers, whose stop and frisk practices indicated a strong tendency toward racial profiling, would now have to produce and record thorough documentation of their stop and frisk activity, complete with the suspects’ races. There are four assumptions underlying this push: that it is possibly to accurately track race (meaning, that

race is something that can be “seen”, and that it will be seen in a consistent manner by law enforcement officials); that it is important to track race; that if we track race and find disparate treatment, we can determine the source of the disparities; and that if we do so, we can cure the disparities via police training,

“blind” case review, etc etc. None of these assumptions, with the possible exception of the second, are immune to criticism: we know racial determinations can be malleable, and as we’ll see in a bit, even determining that disparities exist doesn’t tell us much about why they happen or what to do to correct them.

To complicate matters, most American scholarship on racial disparities sits at the crux of a dual white/black grid, ignoring the existence and importance of other races. This means that even refined and insightful analyses of institutional racism or overt racist behavior lose important dimensions of the problem; not only are entire ethnic groups completely lost, but the black/white grid leads to a tendency to overfocus on inner city crime, missing out on suburban and rural dimensions. In all fairness to American scholars, it is difficult for them to discuss other categories because state and local systems do not consistently or even systematically track the same ethnicities. When Phil Goodman studied CA prisons, he was told “we don’t do Asian”; when Heather Schoenfeld studied the provenance of prison construction in Florida, she found out that Florida prisons don’t “do” Latino.

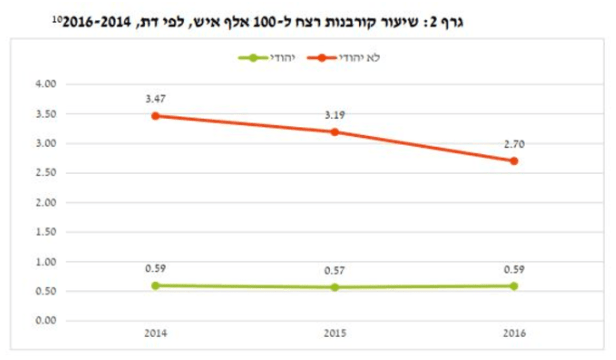

Shifting gears to the Israeli example–while Israeli bureaucracy does not track ethnicity of Jews, it obsessively and fairly systematically tracks other identities–again, from suspect descriptions through booking data, etc. Moreover, because of the political situation and the low rate of Jewish-Arab intermarriage, as well as the distinctive characteristics of names, it is easier to correctly code across the Jewish and Arab divide. Over the years, this categorization has enabled Israeli criminologists–primarily Arye Rattner, Gideon Fishman, and Oren Gazal-Ayal–to conduct large-scale quantitative studies showing significant disparities in arrests and sentencing between Jews and Arabs. A qualitative dimension of the disparity, which is difficult to code but easy to perceive, is the imperfect distinction that Israeli law enforcement systematically draws between “criminal” (i.e., domestic) and “security” (i.e., motivated by the Israeli-Palestinian conflict) incidents. While this distinction itself can and should be the subject of critique (how do you characterize stolen Israeli cars that are dismantled in Palestine?), it leads to disparate treatment in the form of bifurcated legal jurisdictions, different procedural and substantive law, segregated incarceration practices, etc.

What we learn from the American and Israeli examples is that officially tracked categories can teach us about disparities, but they can also be deeply misleading. But even if we are able to observe disparities, where do they come from?

The major pertinent distinction is between criminality and criminalization. In other words, if a particular ethnic group is overrepresented in the criminal justice system, that could either indicate that members of this group commit more crime or that they are being disproportionately targeted by law enforcement (this is what the defendants in

Armstrong v. U.S. (1996) tried and failed to prove at the American Supreme Court.) Making this distinction can be tricky for several reasons. First, criminality and criminalization can and do coexist: people can be committing more crimes than their “fair share” AND disproportionately targeted for them (echoing the cliché that stereotypes become stereotypes because they’re true often enough.) Second, any conversation about racial discrimination is mired in political complications and pushes the limits of the sayable in both academic and policymaking circles. Third, and relatedly, there is a tendency to confound the empirical existence of statistical facts with their possible explanations in an essentialist way that discourages people from openly discussing facts if they think the facts have an unsavory explanation.

Let’s talk about the American comparator first. The statistics are stark and obvious, even though no one will candidly discuss them: official statistics misrepresent the share of black defendants in drug crimes; self reports, which are more reliable for this kind of crime, show no significant difference in buying and selling between white and black people. On the other hand, official statistics are much more reliable indicators of violent crime, and black people commit about four times more homicides than their percentage in the population. Because this is a distressing and inconvenient fact, criminologists and sociologists are at pains to discuss drugs, an area in which the disparities can be explained through criminalization (see Michelle Alexander and others), rather than violent crime, in which the disparities reflect differential criminal behavior (for good critiques of this tendency see John Pfaff, James Forman, and Jill Loevy’s works.)

The outcome of this tendency is that we don’t spend nearly as much time tracking violent crime as we should. It also means that we need to pay attention to confounding variables and what they mean. For example, the racial disparities in bail decisions, which have been the rallying cry to reform bail, go away when one controls for severity of the offense (it’s obvious why: judges use bail schedules, which are like price lists attached to offenses according to severity), and racial disparities in sentencing go away when one controls for class (it’s obvious why: race and class are inexorably linked, a great example of the protean quality of racism in American society.)

This also means that, despite the fact that black violent crime tends to victimize primarily black people, the question “what about Black-on-Black crime?” becomes a racist trope outside the limits of the sayable. Because of concerns about victimization, over the years Black politicians and police officers have relied on the criminal justice system to try and resolve very real problems in their communities, only to find out that the involvement of law enforcement, such as through stop and frist practices and empowerment of police officers to use force, has led to destructive policies. Nonpunitive victims proposing restorative justice, economic reform, or distributive justice tend to be silenced, and nonpunitive suggestions made by outsiders are seen as unwelcome top-down interventions that receive very little buyout from outsiders. This problem is exacerbated by the nature of the social media conversation about disparities, for reasons I explain

here.

Now, let’s turn to the Israeli comparator.

The conversation about Arab on Arab crime is also politically fraught. The Israeli right is at pains to emphasize Arab criminality as inherent and to treat the crime in an essential way, rejecting any responsibility for the squalor, pervasive discrimination, obtuseness, and downright institutional cruelty that might produce crime. The left–including academics–is at pains to silence discussion of the problem (see the

pervasive silencing of female left-wing activists sexually harassed by Palestinian activists.) The assumption seems to be that admitting there is a problem is tantamount to making essentialist assumptions about Arab criminality; in some quarters, there is discomfort with the idea of condemning aspects of Arab culture for contributing to patterns of violent crime (e.g., family honor killings).

What’s interesting is that none of these niceties come from within the Israeli Arab community. In a

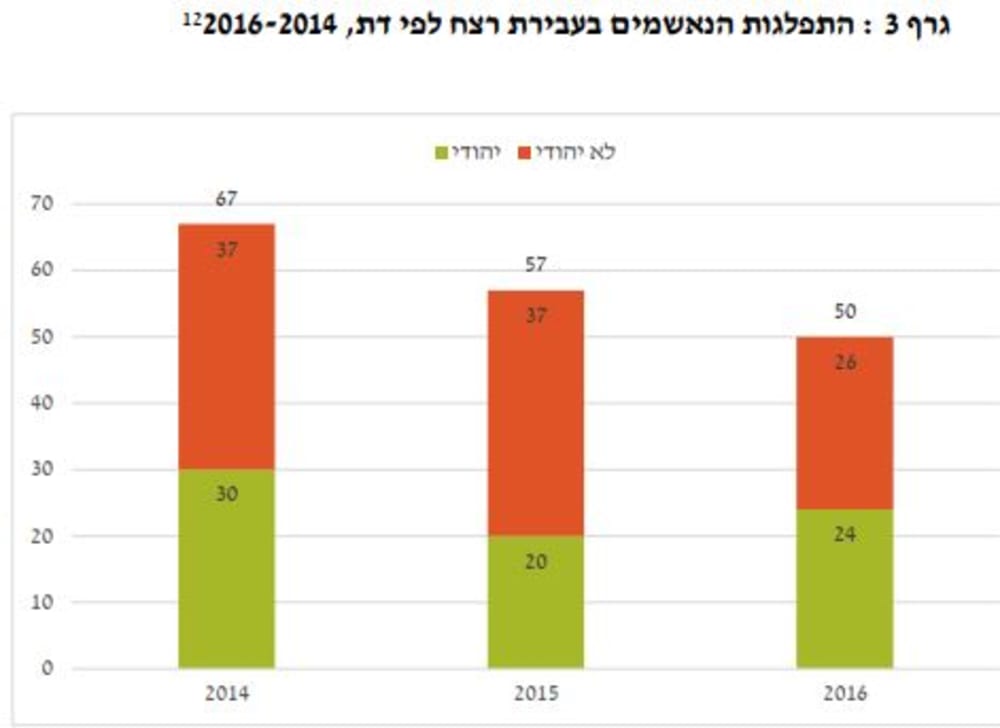

recent New York Times op-ed, Ayman Odeh, leader of the joint Arab party, explicitly flagged the problem of violent crime rates within the Arab community. Shortly after that, p

rotests broke in Magd-Al-Krum over police inaction regarding violent crime. These protests echo James Forman’s analysis of African American calls for “tough on crime” mentality – a sense of community victimization by intraracial crime and a lack of response from the Jewish Israeli establishment. The dark side of this, of course, is that calling police attention to intra-Arab crime hands control to the police, which will typically resort to essentialist oppressive measures against the Arab population. As in the U.S., efforts by academics and reformers to address the problem head on flail because they are perceived as flagging a problem that people either claim does not exist or ascribe to essentialist characteristics.

What does all this mean for Mizrachi representation in the criminal justice system? If Mizrachim are overrepresented in the criminal defendant population, we have to ask ourselves how much of this is due to criminality and how much due to criminalization. We might find ourselves in a situation similar to that of official markers, where different types of crime manifest in different ways–at least some of the overrepresentation might be because of law enforcement and some might be because of various systemic social conditions that produce criminogenic atmospheres in neglected, disadvantaged communities (and, as in the American example, class and ethnicity might be closely correlated.) Official statistics are, as explained above, to no avail here; victim surveys would also be unhelpful, because there’s no reliable way victims might report the ethnicity of their assailants (because physical appearance is not a good indicator of ethnicity in Israel.) Self-surveys might be best, but would be more reliable in non-stigmatizing offenses (such as personal use or simple possession of marijuana) than in violent crime.

In the military crime context, which started me down this path, absence without leave presents a particularly interesting case. For one thing, official statistics are a very reliable way of determining AWOL, because all units keep records on who is absent from leave. However, the length of absence, which is a strong predictor of punishment, is not a good reflection of severity of the offense. The time between deserting the unit and being apprehended is, more often than not, a function of the military police’s work schedule, as deserter catchers tend to target people in particular neighborhoods on particular dates regardless of the length of their absence. Because enforcement is by neighborhood, deserter catchers might be more focused on targeting high-absence neighborhoods, which might also be low income neighborhoods, because AWOL in the Israeli context is largely predicated by socioeconomic needs. A hidden dimension of this is that “criminality” here is directly a function of means, because well-to-do youngsters can avoid criminalization merely by relying on family and friends to get them out of the service duty in legal ways (e.g., obtaining a private psychologist’s written opinion about mental illness), whereas this option is not available to people from disadvantaged backgrounds, who have to recur to illegality to solve their problem. If so, this might imply that class/wealth mitigates the relationship between ethnicity and AWOL offenses–this doesn’t mean there is no injustice toward Mizrachim happening, but rather that the class-ethnicity nexus is inexorable and that stands in the way of a “clean” statistical analysis.

The last step is to ask ourselves how to measure disparate sentencing for the people caught in the military justice system. Beside the difficulties with markers such as names or appearances, there is another reason not to use proxies: it doesn’t actually matter what the person’s ethnicity really is (if, indeed, there is such a thing as “real” ethnicity.) Rather, what matters is how that person is perceived by the judicial system.

One way to address these biases is to use experimental design, particularly factorial vignette surveys. The experiment would utilize two imaginary scenarios which are similar in terms of the crime and differ only in the ethnicity of the perpetrator, signaled by a validated marker (such as socioeconomic information about the grandparents’ country of origin.) and examine judicial deliberation, interpretation of factors, and suggested sentences. AWOL would be an ideal test case, because the facts of the incidents tend to be very similar whereas the personal backgrounds might differ.

Another approach would be to use qualitative approaches. On occasion, overt racism might find its way into judicial decisions (and has definitely appeared in Israeli court decisions): akin to Nicole Gonzalez Van Cleve’s work, in which judges and lawyers ridiculed defendant’s Ebonics, we might find similar things in observations and content analysis. The problem with relying exclusively on this method is that, the more cautious and tactful people are, the less evidence of bias there will be.

Which is why I would like to suggest a mixed-method approach consisting of two steps. The idea behind this one is that what is really behind the judicial approach is what was bothering me throughout all these years: that when judges hear of people’s personal circumstances, they might recognize some lifestyle/preference/family markers that they implicitly (or explicitly) identify as inferior, tasteless, moronic, you name it, and penalize defendants for these cultural markers. Step One would be to create AWOL stories that evoke various such cultural markers and present them to a general population of respondents, asking them to identify scenarios which, to them, “smell” like Mizrachi or Ashkenazi narratives. This phase builds on David Sudnows aforementioned idea of normal crimes–namely, that professionals in the system develop sociological notions of how crimes are typically committed and rank their seriousness accordingly. It may well be that stories such as that of my defendant above “reads” to a general population as a “Mizrachi story”, whereas a story about a young classical musician leaving his unit to play a concert “reads” as an “Ashkenazi story.” Note that this is not to say that the people actually caught in these circumstances are Askhenazim or Mizrachim–just that their stories are perceived as belonging to one group or the other becacuse of their cultural markers. Note also that, by relying on accepted social biases, the researcher is not contributing to the problem s/he is studying, but rather taking a snapshot of social stereotypes.

In Step Two, judicial decisions in AWOL stories would be analyzed to see whether they contain cultural markers that were identified as ethnically appropriate in the previous step, and correlated with sentencing decisions. Again: it doesn’t really matter, and shouldn’t matter, whether the judges associate these stories explicitly (or implicitly) with a particular ethnicity; what this would show is whether a particular perceived “mentality” or “sensibility” is being penalized because it does not correspond to the world of values held by the cops.

There could be two kinds of critiques of such a study: The first is along the lines of “you say it like it’s a bad thing.” If judges think that their lifestyle critique is legitimate, they would be embracing a disparity in sentencing; they might argue that it is universally commendable to penalize someone for valuing his brother’s lavish bar mitzvah celebration over military service and be more lenient with someone who prioritizes, say, academic studies or helping family members out of poverty in a more readable way. The second is a chicken and egg problem: are “Mizrachi stories” perceived as bad per se, and then associated with Mizrachi defendants, or bad because they are attributed to Mizrachi defendants? And if the ultimate outcome is disparity, why does it matter?

Whichever way we decide to go with this, it is important to accept that methods for measuring disparity are imperfect and open to interpretation. But that doesn’t mean we should despair. This is particularly important in the military justice context because of the considerable importance of military service for mobilization in Israeli society. It’s especially notable that, as military sociologist Yagil Levy observes, the Israeli army has gone through simultaneous processes of demilitarization and remilitarization: Ashkenazi male elites are departing the ranks, shifting from combat to cyber and technology, and as a consequence, other groups, lower in the Israeli socioeconomic hierarchy, fill those voids. If the army is an increasing path for Mizrachi mobility, targeting Mizrachim with harsh consequences for AWOL because of cultural stereotypes is a huge problem. The problem is magnified by the fact that some military criminal records, including AWOL convictions, follow the defendants into civilian life and can seriously derail these efforts at mobilization through service.

It is crucial, however, not to give in to the tendency in some progressive circles to “ratchet up”, i.e., to treat more privileged defendants more harshly. If the roots of the problem are in class or culture, they need to be handled as such. And they are probably both. When criminal justice is the only hammer we have, every problem looks like a nail.

__________________