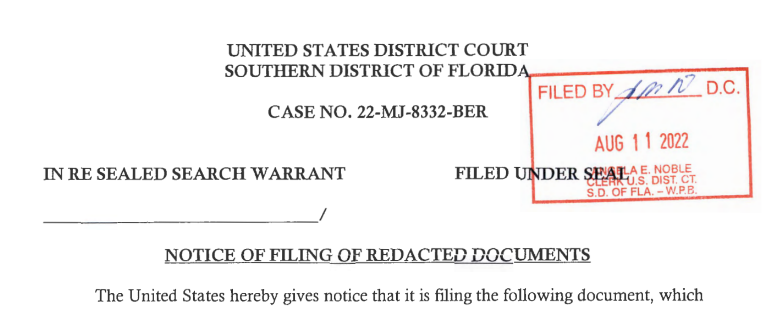

Well, it’s happened: A search of Trump’s Mar-a-Lago residence yielded numerous items, all of which are listed in the search warrant, which you can read here in all its glory.

If you still can’t make heads nor tails of this, it’s because all we have seen so far is the warrant, which lists the place to be searched and items to be sealed, and not the affidavit, in which law enforcement officers detail their probable cause for the judge. As explained here, for reasons involving the ongoing investigation, it is unlikely that we’ll actually see the affidavit before formal charges are brought, so speculation abounds. Nevertheless, there are some things we can learn from the warrant. Here’s the description of the items sought:

a. Any physical documents with classification markings, along with any containers/boxes (including any other contents) in which such documents are located, as well as any other containers/boxes that are collectively stored or found together with the aforementioned documents and containers/boxes;

b. Information, including communications in any form, regarding the retrieval, storage, or transmission of national defense information or classified material;

c. Any government and/or Presidential Records created between January 20, 2017, and January 20, 2021; or

d. Any evidence of the knowing alteration, destruction, or concealment of any government and/or Presidential Records, or of any documents with classification markings.

Contrast this with the three crimes listed in the warrant and you get a fuller picture of the suspicions against Trump. Here’s an excerpt from this New York Times story, which describes these federal laws:

The first law, Section 793 of Title 18 of the U.S. Code, is better known as the Espionage Act. It criminalizes the unauthorized retention or disclosure of information related to national defense that could be used to harm the United States or aid a foreign adversary. Each offense can carry a penalty of up to 10 years in prison.

Despite its name, the Espionage Act is not limited to instances of spying for a foreign power and is written in a way that broadly covers mishandling of security-related secrets. The government has frequently used it to prosecute officials who have leaked information to the news media for the purpose of whistle-blowing or otherwise informing the public, for example.

Importantly, Congress enacted the Espionage Act in 1917, during World War I — decades before President Harry S. Truman issued an executive order that created the modern classification system, under which documents can be deemed confidential, secret or top secret. The president is the ultimate arbiter of whether any of those classifications applies — or should be lifted.

As a result, while these classifications — especially top secret ones — can be good indicators that a document probably meets the standard of being “national defense information” covered by the Espionage Act, charges under that law can be brought against someone who hoarded national security secrets even if they were not deemed classified.

The list of items that the warrant authorized the F.B.I. to seize captured this nuance. It said agents could take “documents with classification markings,” along with anything else in the boxes or containers where they found such files, but also any information “regarding the retrieval, storage or transmission of national defense information or classified material.”

The government has not said what specific documents investigators thought Mr. Trump had kept at Mar-a-Lago, nor what they found there. The inventory of items was vague, including multiple mentions of “miscellaneous top-secret documents,” for example.

But the invocation of “the retrieval, storage or transmission” of secret information in the warrant offered a potential clue to at least one category of the files the F.B.I. may have been looking for. One possible interpretation of that phrase is that it hinted at encrypted communications, hacking or surveillance abilities.

The other two laws invoked in the warrant do not have to do with national security.

The second, Section 1519, is an obstruction law that is part of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, a broad set of reforms enacted by Congress in 2002 after financial scandals at firms like Enron, Arthur Andersen and WorldCom.

Section 1519 sets a penalty of up to 20 years in prison per offense for the act of destroying or concealing documents or records “with the intent to impede, obstruct or influence the investigation or proper administration of any matter” within the jurisdiction of federal departments or agencies.

The warrant does not specify whether that obstruction effort is a reference to the government’s attempts to retrieve all the publicly owned documents that should be given to the National Archives and Records Administration, or something separate.

The third law that investigators cite in the warrant, Section 2071, criminalizes the theft or destruction of government documents. It makes it a crime, punishable in part by up to three years in prison per offense, for anyone with custody of any record or document from federal court or public office to willfully and unlawfully conceal, remove, mutilate, falsify or destroy it.

Given that the ongoing investigation is still shrouded in mystery, assuming that there isn’t some glaring horror, this is beginning to look like Al Capone’s prosecution for tax evasion.